Living Memories, 1987-2010

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson(121)

A quarter century ago Mission Bay was becoming contested land in a way few had ever dreamed of. The former tidelands and open bay that had been granted to the Southern Pacific and Santa Fe railroads as part of the original 19th century federal subsidies to the railroads were still in their possession at the start of the 1980s, long having been turned into “made land.” Southern Pacific and Santa Fe agreed to merge their companies in 1983 but surprisingly, under the very pro-business Reagan Administration, the Interstate Commerce Commission denied the merger.122 After appeals lost, the merged SP-SF company divested itself of the former SP railroad but retained ownership of all the former railroad lands, which they “consolidated” in a new company, Santa Fe Pacific Realty Corporation, instantly becoming California’s largest landowner. In 1990, the name was changed to Catellus Development Corporation (CA=California, Tellus= Goddess of the Land, the winning name proposed in an employee contest).

Aerial view of Mission Bay in 1999, construction of Genentech Hall is underway but the most of Mission Bay still lies dormant.

Photo: from a video by Chris Carlsson

Mission Creek and the houseboat community from the 7th Street end of the channel. Freeway pillars, condominiums, and the Giants ballpark now line the waterway in this 2009 photo.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Potentially among the most lucrative of parcels, Mission Bay had been long touted as an unprecedented opportunity to develop a “city within the City.” Local politicians and developers salivated at the new Gold Rush they could foresee in the 300 acres of undeveloped land. In the urgency and enthusiasm for the chance to reconfigure historic railyards and dilapidated industrial buildings into a new urban zone, little thought was given to the history of the place, nor to the doughty band of residents who were lodged in the Mission Creek houseboat community (though 40-year resident Kevin O’Connell cites a perhaps apocryphal tale that early developers agreed that “before anything could happen, the houseboats had to go”).

The houseboat community and friends from the conservation community formed the Mission Creek Conservancy (MCC) in 1983 and published this very book you’re now reading, albeit in its first edition, in 1986. (Toby Levine, now living in a condo on the North side of Mission Creek, was MCC’s first President.) This intervention into the public process was vital to changing the development dynamics that were beginning to unfold. In the pre-merger development plans, large retailers and highrise office developers were in the saddle. The storied architectural firm of I.M. Pei proposed an early vision of Mission Bay in which canals and ponds were brought from the creek into the land, and then surrounded with highrise offices and condominiums. A later plan included proposals from Home Depot to build a massive retail outlet encircled by a sea of parking lots not far from the southern boundary of the district. Bob Isaacson, long-time houseboater and Mission Creek Conservancy president remembers their fear at the time: “We were looking at a Daly City-type development, with acres of parking lots.”

Mission Creek and the houseboat community under the looming freeway, with the 4th Street bridge spanning the creek, and the new city park on the south shore, summer 2010.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The Conservancy’s early advocacy work included convening wine and cheese parties for Planning Commissioners, presenting slide shows at all kinds of public meetings, and working hard to shift public perceptions. Mission Bay was not a tabula rasa, a blank slate on which developers could act without historic or social context—at least the Conservancy was determined to make every effort to publicize and promote the presence of charismatic shorebirds, the history of the waters, the land, and the prior uses of the place. Board member Ruth Gravanis places the book in historic context:

“We decided to do the book as part of an effort to raise awareness of this resource. Before I even got involved in all this, the Mission Creek Conservancy produced Mission Creek San Francisco, a book of photos about the creek. We really wanted to put this place on the map in the minds of lots and lots of people. Not just for the critters in the creek that needed to be preserved, but also for the rich cultural history of the site that we wanted to see recognized and honored in the new development.”

The Conservancy was fully involved from the beginning and dogged the process. They were joined in this effort by numerous groups and individuals who came together as the Mission Bay Clearinghouse—San Francisco Tomorrow, the Council of Community Housing Organizations, labor representatives, Potrero Boosters, and the Potrero League of Active Neighbors, among others. Also involved were folks living in Dogpatch, the rustic neighborhood between Potrero Hill and the old shipyards, south of the Mission Bay zone. Long-time Dogpatch activist Joe Boss emphasizes the importance of neighborhood involvement in the process: “There have been a core of Dogpatch people and a core of Creek people who have been working for the last 25-30 years with Catellus. It certainly has a lot more human scale and more open space and more thought given to real human beings who would be working there, than there would’ve been…”

“Thank god for mandated public input!” exclaims Mission Creek resident and Conservancy board member Ginny Stearns. The Mission Bay Development process definitely benefited from long years of public battling with the Redevelopment Agency over the destruction of the Fillmore, the South of Market, the old Italian Produce Market, and attempts to bring the wrecking ball into the Mission district too. In fact, “mandated public input” can be traced to the upheavals of the 1960s and early 1970s, when new legal mandates finally pried open closed governmental planning processes and gave citizens new rights to intervene. The Conservancy took full advantage of this, and ultimately, Catellus came to recognize them as one of their best community collaborators.

Early goals of the Conservancy included a major park adjacent to the channel and the creation of a tidal wetland on the fill area known as Seawall Lot 337—held by the Port of SF as part of the backlands for Piers 48 and 50 and currently known as Giants Parking Lot A. In 1991 the Board of Supervisors approved the first Development Agreement for Mission Bay, and, wonder of wonders, it included an eight-acre wetland on Seawall Lot 337. The euphoria of victory was short-lived, however. The project’s assumed economic engine, a previously burgeoning office market, began to tank, and as the economy took a downturn it became clear that the project was going nowhere. In 1995 Catellus announced its withdrawal from the Development Agreement and the plan was dead.

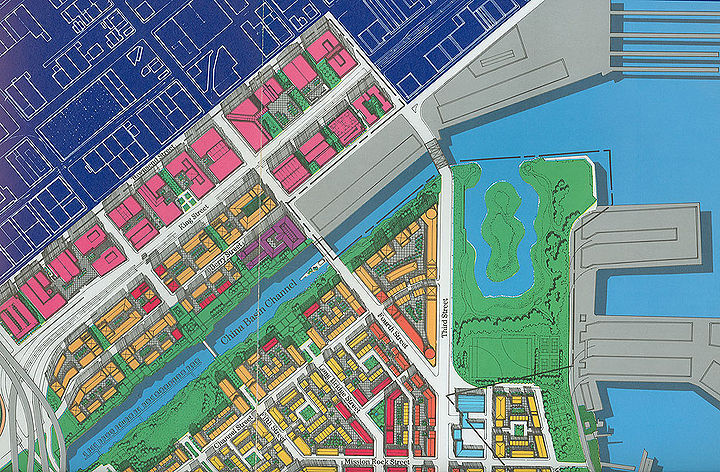

Mission Creek Park plan, c. 1991. Note the area originally known as Seawall Lot 337, now Giants Parking Lot A and McCovey Park, was slated to include an 8-acre wetland.

Courtesy Mission Creek Conservancy

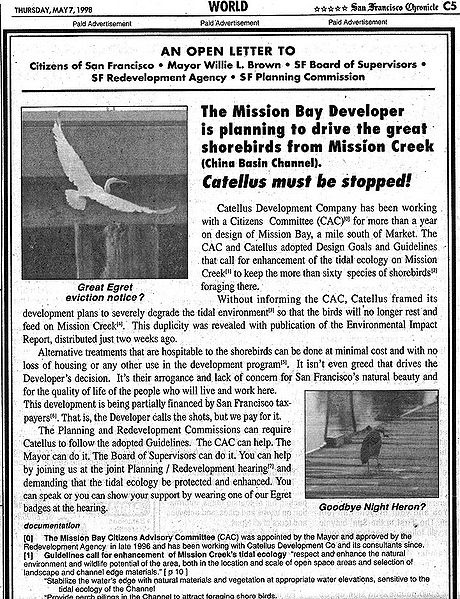

By 1996 a new planning process was well underway for Mission Bay, this time as a redevelopment area (eligible for tax-increment financing) and with UCSF as the anchor tenant and without any possibility of a wetland at Seawall Lot 337. In 1998, Doug Gardner was appointed vice president in charge of the Mission Bay Development by Catellus president Nelson Rising. Just before Gardner’s appointment, an Environmental Impact Report was published describing Catellus’s plans to use rip-rap (broken rock and concrete) along all of Mission Creek’s banks. The Mission Creek Conservancy purchased 1/3 page ads in the San Francisco Examiner and Chronicle saying “Catellus must be stopped” to preserve the rich wildlife on Mission Creek. This rich ecology, most prominent in the great egrets, great blue herons, night herons, grebes, cormorants, pelicans, ducks and many others, should be available to the thousands of people who will live, work and visit here, not destroyed by rip-rap banks which would demolish the food chain. The $30,000 cost of these ads, MCC’s largest expenditure by far in its 30 year history, was donated by its Board members.

Gardner arrived just after the ad was published and asked for a meeting with the “Alliance For A Clean Waterfront,” a loose consortium of citizen groups, including the MCC, that were concerned about the Mission Bay development’s impact on water quality. Bob Isaacson remembers. “He went around the table asking what each of us wanted. Attendees were asking for separated storm and sewage waters, pre-treatment of storm waters, and the like. He made no clear commitments. I told him we had charismatic shorebirds here and wanted to preserve them. He looked me in the eye and said ‘we can do that’. For the next decade he was steadfast in that pledge.”

Ruth Gravanis was a core member of the Alliance for a Clean Waterfront. She recalls that the Alliance, including the Conservancy, pushed “Catellus to do more serious low-impact storm water design things. [It was a] victory to keep storm water and sewage systems separate on the south side of channel. That keeps the door open for doing more innovative things with storm water treatment, like bioswales and water gardens, etc.” Despite its funding of a study of low-impact design storm water options, Catellus decided not to implement them.

Corinne Woods has been a key houseboat community member for a quarter century. She is referred to by some as the “Secretary of State” of the Houseboaters, but officially she has chaired the Citizen Advisory Committee, been on the UCSF Advisory Board, and is a member of the Neighborhood Parks Council Blue-Greenway Project. “I remember going to the approvals at the Redevelopment Commission and standing in the hall with Jennifer Clary and the whole enviro group and them saying, ‘we’re not going to support this unless you’re going to do separation of sewage and storm water.’”123

But the campaign for Mission Creek had a wholistic concern for local ecology too. Bob Isaacson tells the story: “In terms of the environment we had wanted the eight-acre wetland [at Seawall Lot 337], but it wasn’t going to happen. We focused instead on making the creek as viable for wildlife as possible and it’s been very successful. The first Mission Bay plan was going to turn its back on the creek.”

Ginny Stearns: “It’s so well designed. They moved the freeway back, and then turned the creek (that had been a sewer) into an amenity. Now we have a beautiful park all the way around it and down the shore so you have a totally livable environment…There are people on both sides of the watershed who live here because of the creek.”

The public efforts of the Conservancy and others led to a rising profile for the Creek and its environmental potential. Grants from the SF Estuary Project and SF Beautiful were used to re-establish native wetland plants along the banks. And the restoration of native habitat has led to a remarkable renaissance of returning wildlife, as described by Stearns:

The number of birds has increased, as has the number of species. We’ve got a lot of fish coming in here. We had some really exciting feeding frenzies when the herring came in last winter. We had sea lions roaring around, breathing and splashing, pelicans dropping out of the sky, squadrons of cormorants trying to get the fish. We have bat rays now that we never had before. We even have seals now!

Neighbors along the creek like to remember the porpoises who came bounding through the channel within the last year too. Isaacson credits the intelligence of Catellus and its vice-president Doug Gardner while situating them historically too: “He was a product of the time as well. In San Francisco you can’t ignore these issues but the guys before Gardner had been poo-pooing them and they got bounced. If Gardner had been that kind of person, he wouldn’t have lasted at Catellus.”

Shaping a New Neighborhood

“This development is called Mission Bay, and its like Pheasant Hill, there are no pheasants and no hill! Just like there’s no mission and no bay!”

- —Kevin O’Connell, 40-year houseboat resident

Kevin O’Connell has lived on Mission Creek for 40 years following a stint as a long-distance truck driver. “When I first came down here I was greeted with serious suspicion because I had a bit of college. Most of the people here were blue-collar with marine experience—fishermen, ex-Coast Guard, or ex-Navy. Only by dint of the fact that I built my first boat by hand was I grudgingly allowed in. It took me a long time to be accepted by the core community, [which has] since shifted. It’s a microcosm of what’s happened in the City. Forty years ago it used to be predominantly blue-collar, and there were some really tough cookies… (and that was just the women!) It has gradually shifted to an increasingly professional, “better” or more educated class of people.”

Few have lived on the houseboats as long as O’Connell but most share his passionate commitment to their community: “We’re one of the last examples of a genuine democracy…. We really make our own decisions here. We set our own rates, make our own rules, we determine who’s here. It’s nothing like a homeowners association… We’re all volunteers. It’s an amazing glimpse into the possible.”

Those dedicated volunteers were not without their fun side. In May of ’83 the late Jack Davis organized the unparalleled Bridge to Bridge Run, described thusly in Herb Caen’s column: “Who needs Bay to Breakers? The Mission Creek Conservancy is having a ‘Bridge-to-Bridge’ run . . . From the Third to the Fourth St. bridge, a grueling 0.5 kilometers, winners to be democratically determined by lottery. . .” The $7.50 entry fee included a T-shirt and two beers. And not without class. Shoe removal was de rigeur on Betty Boatwright’s houseboat, with its plush white carpet and grand piano.

It was this community and its friends through MCC that in 1988 had instigated some research into the legal status of Mission Bay lands. Should the railroads go on having control over this remarkable real estate, land granted them originally to facilitate the development of the public benefit of continent-spanning railroads? Was there a legal basis for asserting public rights versus the steamroller of private property? A young legal eagle who had played a major role in the Mono Lake campaign, tried to build a case for using the Public Trust Doctrine to halt the total privatization of Mission Bay lands.124

As Public Records Act requests were made in Sacramento, the corporate developers suddenly showed a willingness to allow the 8-acre wetland on Seawall Lot 337. We can only guess if there was a connection between the research and the wetland concession, but in any case it all came to naught as the 1990 “consensus” plan, achieved after a great deal of public input with a broad range of public amenities including the wetland, was dropped.

Mission Creek view on north bank, easterly (above) and wouthwesterly (below).

Photos: Chris Carlsson

As Amy Neches, original Project Manager at the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency for Mission Bay, sees it: “The political process for putting that plan together had resulted in a set of public benefits that was so large and so expensive that as soon as the economy started to go down and it wasn’t the perfect real estate market, the whole thing toppled. Everybody got what they wanted in the 1991 plan, but then they got nothing at all. [In 1996] everyone was a little pulled back: Let’s make sure we’re working towards something feasible. It’s great to have a plan with a bazillion public benefits, but it doesn’t do anyone any good if it never gets built. Feasibility was a litmus test for the ’96 plan, [and the] community groups were reasonable.”

While this public process was underway, another story was unfolding that would have an enormous effect on the neighborhood and the entire plan for Mission Bay. In 1992, San Francisco Giants baseball team owner Bob Lurie announced that he’d sold the team to some Florida investors and the Giants would open the 1993 season in Florida. Local politicians, notably Supervisors Doris Ward and Angela Alioto, moved quickly to outmaneuver Lurie’s plans. The City Attorney mounted a full-court press to keep the team, and one of the lawyers they brought in to help was Jack Bair, a local baseball fan and attorney, who had already been involved in the earlier ill-fated attempts to locate a new “downtown ballpark” at 7th and Townsend and at China Basin.

Ferries deliver fans via Mission Creek docks to August game at AT&T Park, Summer 2010.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The San Francisco Giants, behind their ace Tim Lincecum face the arch-rival Los Angeles Dodgers in an August 2009 game. Not uncommon at the ballpark, a tall-masted ship passes in “McCovey Cove” behind the right field fence during the game.

Photos: Chris Carlsson

The City Attorney, with Bair’s participation, was successful, and the Giants stayed in San Francisco, ultimately being sold to a new ownership group led by Safeway executive Peter Magowan who vowed to keep the team in the City. Jack Bair was hired as the new corporate counsel and VP for the team, and led the effort to locate and build a new ballpark.

Pacific Bell Park opened in 2000 and already changed its name twice in its first decade, following the mutating identities of its corporate sponsor. Scattered public efforts to christen it “Willie Mays Field” after the Giants’ legend never fully took hold. The Giants have a reputation as a good neighbor with the houseboaters and residents of the thousands of apartments around the north side of the creek and the South Beach neighborhood stretching towards the Bay Bridge. Unlike relationships between stadiums and some urban neighborhoods, the whole neighborhood doesn’t stop during a game. Locals are free to stroll around the ballpark’s waterfront promenade, and if interested, can spend an inning or two taking in the game from the free “knothole gang” zone the Giants built in the right field fence. After ten years of great attendance, the franchise is again well rooted in San Francisco.

Amy Neches has been deeply involved in planning the area and for the most part is very satisfied with the results so far, and characterizes her work at Mission Bay as “the pinnacle of my professional life.” She has an open-minded frankness about what has been built so far: “I always feel like Mission Bay is an experiment in density, design, and infill. A lot of things are fabulous, and some are unfabulous. We won’t know until more gets built, and lived-in. Most of it has come out really well. Some design things, I look at and go ‘unh’…”

Dogpatch’s Joe Boss is disappointed. “It’s all been hard fought, and mostly good. In some cases there should have been taller buildings, and in some parts no buildings. It’s not a total disaster. But it certainly could have been a lot better.”

For many San Franciscans, the Mission Bay neighborhood has a distinctly suburban feel so far. UCSF has built a series of 5 story blocks, creating a dully neutral campus, aping the corporate campuses of the South Bay. Nearby office buildings and condominiums feel like they wandered up from Silicon Valley and got stuck here. Maybe the aesthetic objection to the office parks of Mission Bay shares sentiments with San Francisco’s decades-long anti-highrise movement? Corinne Woods remembers the forces that shaped the footprint and profiles of Mission Bay buildings:

“Don’t forget we were in a super anti-highrise mood in San Francisco. They had just passed the height limits on the waterfront. San Francisco Tomorrow was saying ‘we don’t want any height at all.’ If you’re going to build down to bedrock in unconsolidated fill and pile-drive it 350 feet down, and you can’t build up because the community doesn’t want highrises, you’re going to have broad blocky buildings.”

As it happens, the biotechnology industry that is beginning to cluster around the UCSF biomedical campus is naturally drawn to the architecture and landscape of Mission Bay. Neches puts it bluntly: “We basically brought the suburbs here in terms of bio [science industries]. Just getting those guys to accept what they consider the lack of parking, what everyone else in the city considers excessive parking, is a huge hurdle. We’re not talking about groovy web 3.0 companies. These biotech companies are suburban guys. They’re here now in SF because we’re building beautiful buildings next to the University. They’re not interested in brick-and-timber places.”

One of the bio-tech companies associated with UCSF’s presence is the Gladstone Institutes, a pioneering non-profit company of advanced labs doing research into neuropathology, virology and immunology, hiv, cardiovascular disease, aging and age-associated diseases including Alzheimers, and more. Bob Mahley, recently retired President who moved Gladstone Institutes here and his wife and working partner Linda, live in a condo on the north side of Mission Creek, relishing the walk to work. He and Gladstone are committed to research in areas where for-profit companies don’t see clear near-term profits.

Andrea Jones worked for Catellus for a decade before becoming a Bosa Development vice-president a few years ago. She says condominium buyers in Bosa’s Radianz project on Terry Francois Boulevard “like being near the water, they like the views. They can’t get that in a downtown condo. Here it’s a mixed urban/suburban feel. People like sitting out there and looking at the water, like more of a suburban area, but they can see downtown, and they’re only a few minutes away.”

Amy Neches, though leading the Redevelopment Agency’s Mission Bay planning since the mid-1990s, “is always amazed that it’s here at all!” Massive urban development schemes have to overcome endless obstacles, from the activist public to the government, internal corporate culture and financing, and much more. There’s a quick consensus among today’s stakeholders on who finally got Mission Bay on track. Joe Boss says “I think UCSF could not have happened had not Willie Brown done the things that he did. But the City is going to be paying for that for years,” since UCSF pays no local property taxes. Amy Neches explains how it worked:

Mission Bay moved forward because there was amazing leadership from the University’s Bruce Spaulding, the City’s Mayor Brown who was able to get his department heads to move things, and Nelson Rising at Catellus. Say what you want about Willie in his later years, but he was a guy who when he said ‘I am going to make something happen,’ he made it happen. That was very important. Catellus’s Nelson Rising was a very smart guy and he had a good team. Rather than start at some extreme [to begin bargaining], they came in with a good plan, and they communicated with the public on a very open basis. The basic plan had a good balance of public benefits and private feasibility.

San Francisco has sought to build a new neighborhood with the new UCSF campus as its anchor. This has enjoyed broad public support, and the neighborhood is now taking shape around it. The City’s effort to learn from past mistakes with respect to its previous redevelopment projects and other buildings has already seen some success. Neches describes the emerging district: “This is one of the most economically diverse neighborhoods in the city. We are now well over 20% affordable housing. We have low-income seniors, low-income families, people with HIV/AIDS. We actually have economic and racial diversity here. We wanted our affordable housing to look good and it does. When Mission Bay is done it’ll be a little over 30% affordable housing.”

It’s also a neighborhood with greater integration of residential and workplace structures than many other parts of the current city. The bioscience campus is attracting biotech and other businesses to move to the adjacent office and laboratory developments. But Americans are notoriously indifferent to history, which means keeping the past alive at the new Mission Bay will take an extra effort. With all the new homes and jobs and incoming residents, the area’s history could be overrun, especially given American culture’s preference for the new and shiny.

To the great benefit of the new neighborhood, there is a solid core of residents with a strong commitment to the area’s history. Already the Mission Creek houseboaters have developed relationships with new condo dwellers across the creek. Some of them are taking up the challenge of sharing the natural and historical wonders of Mission Bay with their new neighbors. Lyla Materon Arum and Mike Wang moved in to 255 Berry Street in 2004 when there was little else open in the area. Lyla is now a Mission Creek Conservancy board member and she and Mike are doing outreach to newcomers. Lyla describes a couple of her business associates who live nearby: “Two of my colleagues live at the Palms. They’ve never heard of Mission Creek, have never walked the promenade, they don’t know anything about this area.”

Most of the newcomers are either older folks ready to or already retired, or new professionals or young couples buying first condominiums in the area. The young professionals commonly work 50-70 hours a week and have little time to explore or research the Creek or the neighborhood’s history. But living in the area gives them the opportunity to enjoy the fruits of their predecessors’ efforts.

Canoe paddlers enjoy a bucolic moment on Mission Creek summer 2010. Mission Bay housing on north bank complete.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

All of which is to say that the neighborhood that is emerging in Mission Bay is far from finished. Perhaps after another quarter century, after thousands of students have matriculated through UCSF and children have been born and raised in the area, and the parks bordering and running through the area are heavily used by folks from all over the city, Mission Bay will feel less like a suburban office park and more like a fully integrated neighborhood of San Francisco. The foundations for a rich, diverse, and flourishing neighborhood have been established through a complicated dance of public and private interests. Only the passage of time will reveal how well those foundations serve the needs of a dynamic and healthy city.

This is chapter seventeen of "Vanished Waters: A History of San Francisco's Mission Bay" published by the Mission Creek Conservancy, and republished here with their permission.

NOTES

121. Interviews for this chapter were conducted during July-August 2010 in several sessions with the following individuals: Bob Isaacson, Ginny Stearns, Barbara Bagot-Lopez, Ruth Gravanis, Bob and Linda Mahley, Joe Boss, Kevin O’Connell, Mike Wang, Lyla Materon Arum, Amy Neches, Tony Bolach, Andrea Jones, Corinne Woods, and Jack Bair.

122. Southern Pacific Santa Fe: The railroad that wasn’t, June 17, 2010, http://examiner.com.

123. All that public pressure worked. A September 2009 summary by the Redevelopment Agency describing the final policy for storm water treatment: Mission Bay South includes an innovative “split” water treatment system. Storm water runoff will be treated onsite and released to the Bay through a series of pump stations, rather than being directed to the Southeast Water Pollution Control Plant to be treated together with wastewater as is typical throughout the City. This will reduce the impact of the project on the Southeast communities, and will serve as an environmental demonstration project for progressive water management practices.

124. The Public Trust Doctrine is a common law concept dating to Roman times and incorporated into the Magna Carta in 1215, providing that air, running water, and the sea plus the lands between high and low tides are permanently in the public domain, to be guarded by the state as the trustee of the public’s interest.