BANK OF CALIFORNIA and WILLIAM RALSTON

Historical Essay

by Gray Brechin

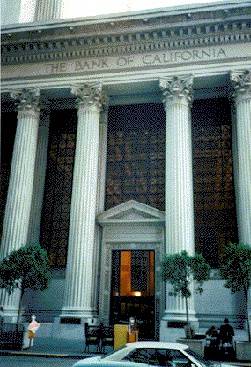

Bank of California at Sansome and California, founded in the 1860s by William Ralston.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

From the moment he arrived in San Francisco in 1854, William Ralston was a leading player in the high-stakes game of Western exploitation. In a land whose abundant resources had scarcely been scraped and whose real estate values climbed with each new immigrant, the future belonged to the ruthless and to the lawyers who wrote the rules of the game for them. They were frequently the same.

Ralston dabbled in a number of schemes before finding his lode. Some things like helping to finance the takeover of Nicaragua by soldier of fortune William Walker just did not pay off. It was to the Comstock Lode south of present-day Reno that "Billy" Ralston hitched his star soon after its discovery in 1859. Five years later, he was treasurer or director of most of the bonanza mines. In that year, Congress admitted Nevada into the Union as San Francisco's most lucrative colony, a state commonly known as the nation's "great rotten borough."

Also in 1864, Ralston established The Bank of California. To his former partners' displeasure, Ralston took most of their best clients with him when he left to found the rival bank. Rumors abounded that Billy had been paid $50,000 to do so by the twenty-five or so bank directors with whom he surrounded himself. With these men, Ralston entered ever-shifting partnerships and betrayals. They became known as Ralston's Ring, or simply, The Bank Crowd, and they constituted the West's wealthiest capitalists during the Civil War period.

For the titular head of the Bank, Ralston enlisted Sacramento's Darius Ogden Mills, the most respected financier on the Coast, though Ralston actually ran the Bank as its Cashier. As his agent on the Comstock, Ralston installed a stock jobber named William Sharon.

To call Sharon a piranha would be to insult the character of the fish. Sharon adroitly devoured mines, mills, business associates, transportation, forests, and Virginia City's water works. He expertly manipulated the stock market with the advantage of insider information gleaned from the mineheads. He directed the profits back to his partners in The Bank Crowd.

Ralston converted his Comstock capital into coastal transport, insurance, telegraph lines, currency speculation, woolen and silk mills, canal companies, hydraulic mines, political and judicial bribery, Alaskan furs, gas works, refineries, and hazardous real estate schemes. It seemed that there was scarcely an enterprise in which Billy Ralston did not have an interest. Collis P. Huntington, boss of the Central Pacific Railroad, wrote to his partner Mark Hopkins: "I think time will show that Ralston has got a larger institution than he is able to run." Ralston returned Huntington's trust by referring to him in coded telegrams as "Hungry." Both were astute judges of character.

As long as Ralston rode the wave of riches, he was the city's paragon of virtue, a role model for pecuniary emulation. His lavish entertainments, his carriages, his ducal estate at Belmont, and his many charities earned him, like Keating later, a deserved place in the developmental history of his adopted city. He was, unquestionably, a visionary; his discussions with Frederick Law Olmsted, for example, led to the cultivation of Golden Gate Park. If it took insider trading, backstabbing, and wholesale political corruption to accomplish his ends, those were the rules of the game and everyone else who could afford to play was doing the same. Fortunately for Ralston, William Sharon cared little for popular opinion and served as the genial banker's lightning rod.

A confidential letter from Ralston to his partner suggests their modus operandi. Ralston advised Sharon to go easy on a wealthy associate who owned valuable stock that they wanted. "Give him sugar and molasses at present, but when our time comes give him vinegar of the sharpest kind. He is our friend and I think will assist us."

Ralston's banking partner in New York wrote him in 1870 that "Everybody talks about you, your princely hospitality, and large-scale of expenditures ... All who go to California want to see you and want letters of introduction."

During the silver boom of the 1870s, San Francisco's Montgomery Street became known as the Wall Street of the West. Just as Manhattan's Wall Street dead ends at Broadway, so did Montgomery stop cold at Market. Ralston had plans to extend Montgomery's high-value real estate to potentially valuable land which he owned south of Market. Such an extension would require cutting through city blocks and leveling a hill on which his fellow magnates had built their mansions. No matter how powerful Ralston was, equally determined plutocrats who were not in on the deal blocked his New Montgomery Street two blocks south of Market, and that presented problems.

As Ralston's other investments turned rancid, the banker needed the lots he owned along New Montgomery to appreciate as planned. To attract investors to his land, he first built a million-dollar hotel called The Grand on the east corner of Market and New Montgomery. When that failed to work, he began The Palace on the western block.

The Grand Hotel (left) and the Palace Hotel (right) on either side of New Montgomery Street where it goes south from Market, c. 1890s.

Photo: Online Archive of California

The building neared completion as Ralston's empire fell about him. He'd never been hampered by a firm boundary between his bank's finances and his own. He began selling properties and borrowing money on nearly everything that he owned and much that he didn't. Among the latter was San Francisco's private water company, on which he had an option and which he counted on selling back to the city at enormous profit. Other experiments in creative accounting included secretly over-issuing Bank of California stock. He borrowed $300,000 on Southern Pacific bonds which he'd removed from the bank vaults.

Pyramid schemes based on the fantasy of perpetual growth are notoriously flimsy and grow more so as the economy slows down. On August 26, 1875, as rumors swept San Francisco, a run began on the Bank of California. At 2:35 PM, its vaults empty, the bank closed its doors and thousands faced ruin. The details of their failures have never been told.

Ralston's corporate board summoned him to appear the day after his bank closed. It seemed that he owed the institution nearly five million dollars, approximately its entire capitalization. All directors professed shock and claimed to have no inkling of their partner's felonious activities, though subsequent lawsuits blew holes in their avowed naiveté. Years later, when lawyers cornered Darius Mills with a subpoena at the Palace Hotel, he suddenly grew deathly ill, retired to his bed, and lost all memory of everything pertaining to the management of the bank during his presidency.

On August 27, 1875, however, Mills' mind was in fine shape. He and his partners forced Ralston's resignation. They also made him sign over all of his assets to William Sharon whom, they trusted, would attempt to straighten out the mess. Ralston left the bank for his daily swim.

He was a strong swimmer, but on the day of his downfall, he was under considerable stress. An hour after plunging into the Bay, his body was retrieved by observers who watched him flounder and sink.

William Sharon had recently been elected to the U.S. Senate from Nevada, thanks to the generosity of his "sack bearers" in the Silver State. It was in the Senator's best interests to rehabilitate Ralston's reputation, for California law held him and his partners financially liable for the failed bank's debts. He did so with the same skill with which he played poker and the stock market.

Fifty thousand mourners marched in the banker's funeral cortege. Orators thundered his virtues. The Alta California mourned that "His was the vast vision of the Builders and his like shall never pass this way again." Ralston biographer David Lavender claims that Sharon deliberately prolonged the city's "emotional jag" to make the work of the bank's reorganization committee easier. Sharon chaired that committee.

The reclamation of both Ralston's reputation and institution worked like a charm. On October 2, 1875, the new Bank of California opened its doors. Jubilant crowds surged from the bank to the nearly-complete Palace where Senator Sharon delivered a touching eulogy to his late friend. In addition to the Palace, Sharon now owned the Grand Hotel, New Montgomery Street, Ralston's country estate and town house, the city's water works, and so many other lucrative properties that he, rather than Ralston's widow, could claim to be California's second wealthiest citizen. He just trailed Darius Mills who soon left the State to cultivate a major dynasty in New York City. Sharon founded his own in California with his vastly enhanced fortune.

San Franciscans argue to this day whether Ralston's death was accidental. Historian Hubert Howe Bancroft, Ralston's contemporary, had no such doubts; in his copy of a city history, Bancroft scrawled in the margin "Ralston, though a daring, dashing pet of the people was a bad man and committed suicide rather than face his friends, after his frauds should become public. [sic]"

from "Pecuniary Emulation" in Reclaiming San Francisco: History, Politics and Culture, City Lights Books, 1998