Bending the Law to Serve Power: Justice Stephen J. Field

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

Stephen J. Field became the Chief Justice of the California Supreme Court just two years after getting elected to the court in 1857. A '49er who settled in Marysville after a short time in San Francisco, succeeded David Terry as the California Supreme Court’s Chief Justice when Terry lost his re-election bid in 1859 (subsequent to his famous duel with the anti-slavery David Broderick in which Broderick was slain by Terry). Towards the end of the Civil War, President Lincoln appointed Field to the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals and weeks later to the U.S. Supreme Court.

On the Supreme Court, Justice Field carried out a systematic program of judicial activism in support of using the newly passed (in 1868) 14th Amendment’s guarantees of “due process” and “equal protection of law” not just to protect freed slaves but to radically expand the rights and powers of corporations. Today’s simmering campaigns against “corporate personhood” are efforts to untangle and reverse the judicial precedents set originally by Justice Field and his colleagues on the 9th Circuit Court, and eventually incorporated into federal judicial decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Justice Field was notorious in California and Washington for his sympathies and personal ties to the Central Pacific railroad leadership, in particular Leland Stanford. He was admonished in 1875 by U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Waite, himself a former railroad lawyer, that he shouldn’t write the majority decision in the case of United States v. Union Pacific because it was “specially important that the opinion should come from one … who would not be known as the personal friend of the parties representing these railroad interests.” (For a thorough treatment of Field’s conflict of interest and role in assisting the Central Pacific, see Ted Nace’s excellent book Gangs of America (Barret-Koehler Publishers, 2003: San Francisco)).

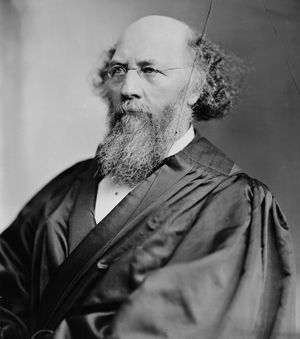

Justice Stephen J. Field

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In the late 1870s, the railroads were under legal and political pressure from insurgent movements of farmers and workers. The Grange movement claimed 850,000 members in over 20,000 chapters across the country, including in rural California, and their militancy led to new regulatory laws being passed. In an Illinois case, the Supreme Court voted 7-2 to uphold regulation of railroad and grain elevator rates against a claim that it violated the due process requirement of the 14th Amendment, invoking a principle articulated in the 1600s by a British judge that held “when private property is ‘affected with a public interest, it cease to be juris privati only’.” Justice Field dissented, writing that if property “affected with a public interest” is fair game for regulation, then “all property and all business in the State are held at the mercy of a majority of its legislature.”

By the early 1880s two cases involving local property taxes and the Southern Pacific Railroad invoked the “equal protection” clause of the 14th Amendment to insist that the corporate behemoth should be treated the same as the small family farm when it came to assessing the value of its properties. Justice Field, along with his ally on the court Justice Sawyer, ruled in favor of the corporation, and in the latter case especially, Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad, the notion that a corporation was a person under the law got a foothold, though initially the claim was made on behalf of the shareholders of the corporation. This of course disregarded the purposeful advantages of incorporation for the individual in terms of absolving them of responsibilities for the corporate behavior or liabilities, that is, they escaped the traditional liability to the community that had normally gone with the ownership of property.

The doctrine of “corporate personhood” required a good deal more obfuscation and manipulation in the federal government to become the customary law of the land that it is now. A court reporter and a Senator both played key roles, but for that tale I refer the reader to Nace’s Gangs of America.

Justice Stephen J. Field plays an important role in making the western neighborhoods, the “outside lands” of the Sunset and Richmond districts, part of San Francisco. But he also was involved in a sordid scandal that rocked one of San Francisco’s nouveau riche families, that of William Sharon. Sharon had been one of the lucky winners that emerged from the wreckage of William Ralston’s vertically integrated silver-stock-and-banking empire that collapsed ignominiously in 1875. Sharon became a multimillionaire silver baron and eventually the Senator from Nevada before he died in 1885. Before he passed, a woman named Sarah Hill demanded a divorce and her share of his assets, claiming that they had been secretly married. It was during the drawn-out court hearings on this case that Mary Ellen Pleasant became a well-known character in 19th century San Francisco for her revealing confirmations of Hill’s relationship with Sharon. Hill won her case and had every intention of taking her spoils and marrying David Terry, the same former California Supreme Court Chief Justice who had killed David Broderick in the famous duel more than two decades earlier.

Sharon’s heirs appealed the case and it was Justice Stephen Field who heard their case and ultimately ruled in favor of Sharon’s heirs and against Sarah Hill. On September 3, 1888 Sarah Hill stood up in court and accused Field of having been bribed by Sharon’s heirs and in the ensuing ruckus both Hill and David Terry were jailed. A year later Field and his friends got on a train near Stockton, California on which David Terry and Sarah Hill were already traveling. During a lunch stop, Field’s bodyguard shot and killed Terry—whether or not Terry did anything to provoke it was hotly disputed by different witnesses.

Justice Field and his Supreme Court colleagues held that his bodyguard had carried out his obligation to protect Field and thus was not guilty of murder. Field remained on the Supreme Court until Dec. 1, 1897 and died two years later well into senility. By then the overarching power of corporations had come to rule the United States during the height of the Gilded Age, an outcome that Field was instrumental in bringing about, even though he died with only $65,000 in assets, apparently not “on the take” as so many “friends” of the railroads had been during the late 19th century.