Berkeley's Sanctuary Movement

Historical Essay

by Kat Jerman

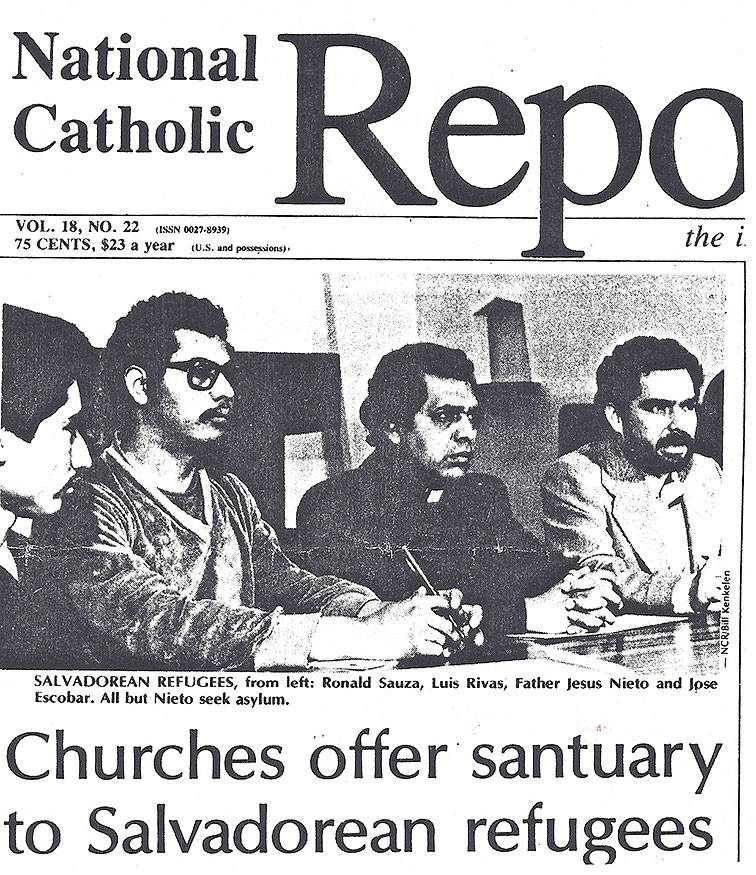

| On March 24, 1982 five churches in Berkeley, California and the Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson, Arizona held coordinated press conferences that launched the modern day “Sanctuary Movement” in the United States. They demanded that the U.S. government meet its moral and legal obligations to grant asylum to the thousands of Guatemalan and El Salvadoran civilians fleeing civil war and U.S.-funded death squads in their home countries. The six congregations publically declared their intent to “provide sanctuary—support, protection, and advocacy”—to undocumented Central American refugees who requested safe haven from deportation. [1] Following their lead, religious communities throughout the Bay Area and across the country flocked to support the newly christened “Sanctuary Movement.” |

Gathering in front of assembled reporters at Berkeley’s University Lutheran Chapel (ULC), representatives of the five Bay Area churches—University Lutheran, St. John’s Presbyterian, St. Joseph the Worker, St. Mark’s Episcopal, and Trinity Methodist—were joined that Wednesday morning by three Salvadoran asylum-seekers, who had agreed just days before to take the risk of speaking publicly in hopes of galvanizing support for the congregations’ efforts and drawing attention to the worsening situation in El Salvador. [2] The three men, comprising a medical student, a teenager, and a survivor of the 1980 Ajo tragedy (in which thirteen Salvadoran asylum-seekers died in the Arizona desert after being abandoned by their coyote), would be the first to formally accept the East Bay churches’ offer of sanctuary. [3]

March 24, 1982 press conference at University Lutheran Chapel.

Credit: http://www.share-elsalvador.org

Prior to their public declaration of sanctuary, each of the original five Berkeley congregations went through extensive educational processes, consulting with refugees, lawyers, theologians and historians and reflecting at length as a congregation before. voting to adopt a ‘sanctuary covenant’ drafted by St. John’s lay member Steve Knapp. [4,5] This covenant, with its tripartite vow to support, protect, and advocate for refugees, would inspire congregations of all faiths and become a model for churches, temples, and synagogues around the country. [6] As sanctuary proponent Robert McAfee Brown of Berkeley’s Pacific School of Religion later noted, the decision to frame their efforts by “invok[ing] the ancient tradition of ‘sanctuary’” gave the movement great appeal to both religious and secular communities, for while “its legal power is nil, its symbolic power is impressive - churches and synagogues as places where people are free of intimidation, harassment, and, now, deportation.” [7]

The Berkeley congregations created the East Bay Sanctuary Covenant (EBSC), a collective grassroots organizing structure to coordinate their efforts to shelter, aid, and advocate for refugees. The EBSC grew rapidly, and soon exceeded thirty member congregations from Berkeley, Oakland, and Albany, California, including Protestant and Catholic churches, Buddhist temples, and at least five synagogues. [8] It was joined by regional covenant committees from San Francisco, Marin County, the South Bay, Sonoma, and other Bay Area communities, which by 1986 formed a regional alliance known as the Northern California Sanctuary covenant, with a focus on national organizing. [9] In addition to publicly declared sanctuary congregations, a much larger web of supporting congregations developed, exceeding 600 nationally by the end of 1983. [10]

In addition to offering several asylum-seekers physical refuge from deportation, sanctuary congregations and supporters engaged in a wide variety of activities, both humanitarian and political. The EBSC office coordinated approximately 200 volunteers a week from local sanctuary congregations, including hundreds of volunteer lawyers who helped with legal advocacy and fighting deportation orders, dozens of medical personnel who volunteered services each week, and countless lay members who assisted refugees in accessing food, work, housing, and daily transportation. [11] In addition to providing direct services, the EBSC also participated in education and political advocacy, lobbying Congress and the President for changes in immigration and foreign policy and developing a robust speakers bureau that conducted outreach to other faith communities and to the general public. Finally, at the request of their colleagues at the San Francisco-based refugee organization CRECE, sanctuary congregations participated in hundreds of solidarity delegations to Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador, bearing witness, providing protection, and building lasting relationships with their Latin American counterparts. [12]

Reverend Gus Schultz with Alejandro, a Salvadoran Refugee, at ULC, 1985.

Photo: Swift, Harriet. "Bay Area Sets Pace for Refugee Sanctuary." Oakland Tribune 22 Feb. 1985: n. pag. Rpt. in The Sanctuary Movement. Oakland: Data Center, 1985. 59-60.

By early 1985, the three-year-old Sanctuary Movement had spread to all sections of the United States, with more than 200 publicly declared sanctuary congregations nationwide, and as many as 800 more offering other forms of support or acting as sanctuaries in secret, according to ULC Reverend Gus Schultz. [13] In the Bay Area alone - still a critical hub and a recognized “pacesetter” for the movement - some fifty faith communities from all denominations had formally answered the call to sanctuary.[14]

In February 1985, the City of Berkeley would again step into the spotlight, opening a new front in the Central American Sanctuary Movement. Through their tireless organizing in defense of the waves of Salvadoran and Guatemalan asylum-seekers who were pouring into the country, for whom deportation could mean death, “East Bay congregations and church leaders influenced municipal governments … to extend similar protections.” [15] On February 19, 1985, the progressive Berkeley City Council voted 8-1 to approve a resolution declaring all of Berkeley a sanctuary for undocumented refugees. [16] The measure, which would pave the way for the creation of “sanctuary cities” nationwide, prohibited Berkeley police or other city employees from assisting federal immigration authorities in the arrest and deportation of Central American asylum-seekers and ensured that city services would not be denied to those refugees or to institutions supporting them. [17] “Let the federal government do its own job,” declared Berkeley Mayor Eugene “Gus” Newport at the City Council meeting that evening, expressing hope that the measure would pave the way for other cities to follow. [18] Mayor Newport, who introduced the ‘City of Refuge’ resolution with strong support both from local representatives and the then-existing dozen or so Berkeley sanctuary congregations, stressed the importance of the effort, not merely as a humanitarian gesture, but a means for raising awareness and for sending a clear message to the Reagan administration “that the American public does not support the use of our tax dollars to support repressive governments that people have to flee.” [19]

Within days of Berkeley’s action, other cities began following suit in expressing support for the movement and their local sanctuary congregations, adopting policies ranging from largely symbolic non-binding resolutions to “enforceable municipal ordinances” that legally restrict local government compliance with federal detention requests. [20] Los Angeles declared itself a City of Refuge that November, insisting that “the tragedy of denying entry to Jewish refugees in the 1930s and 1940s must not be repeated.” [21] San Francisco adopted its own resolution one month later, in response to extensive organizing by Bay Area sanctuary congregations. [22] Beginning in California, several colleges and universities similarly embraced the strategy of declaring sanctuary, forming the Inter-Campus Sanctuary Network, and by 1987, twenty-four U.S. cities, dozens of university campuses and other secular institutions, and even two states—New York and New Mexico—had proclaimed themselves safe havens for Central American refugees. [23]

Initially, advocates of Berkeley’s trailblazing 1985 resolution had emphasized the measure’s symbolic importance, freely admitting that the practical impact of such an extra-legal policy remained an open question. Reflecting back in 2015, however, members of the East Bay Sanctuary Covenant declared that the “safety-net role” of Berkeley’s sanctuary policy had proven “profound,” minimizing some of the daily stress and fear that their undocumented clients face, while keeping them safe in their interactions with city officials. [24] While the broad range in definitions makes counting “sanctuary” localities somewhat difficult, a 2016 report found that 39 cities, 364 counties, and at least four states—including California—continue to serve as sanctuaries, with legislation limiting local law enforcement cooperation with federal immigration authorities. [25]

A Pre-History To The Refugee Sanctuary Movement

The earliest roots of “sanctuary” as a concept date back to Hebrew scripture, in which temples or even entire cities could be designated as sanctuaries, where those falsely accused of crimes could escape retribution. In Roman and medieval societies, Christian churches were recognized as places of refuge for fugitives or those fleeing persecution. [26] Early proponents of the sanctuary movement drew inspiration from a long legacy of offering safe haven, such as the churches and individuals who helped shelter Jews during the Holocaust. As Mayor Gus Newport observed in regard to Berkeley’s “City of Refuge” vote, “the first sanctuary system this country ever knew was the Underground Railroad for black slaves.” [27]

The vanguard role that the San Francisco Bay Area, and the city of Berkeley in particular, played in the emergence of the sanctuary movement during the Central American refugee crisis of the 1980s began taking shape many years earlier. The original five Berkeley sanctuary churches, each located in close proximity to the University of California, Berkeley campus and active participants in the progressive social and political movements that brought Berkeley to international attention in the 1960s and 1970s, were heirs to a long tradition of organizing around social justice issues, both at the congregational and individual level. [28] During the Vietnam War, this activism led the congregations, and ultimately the city, into a confrontation with the federal government that would pave the way for the development of Central American sanctuary a decade later.

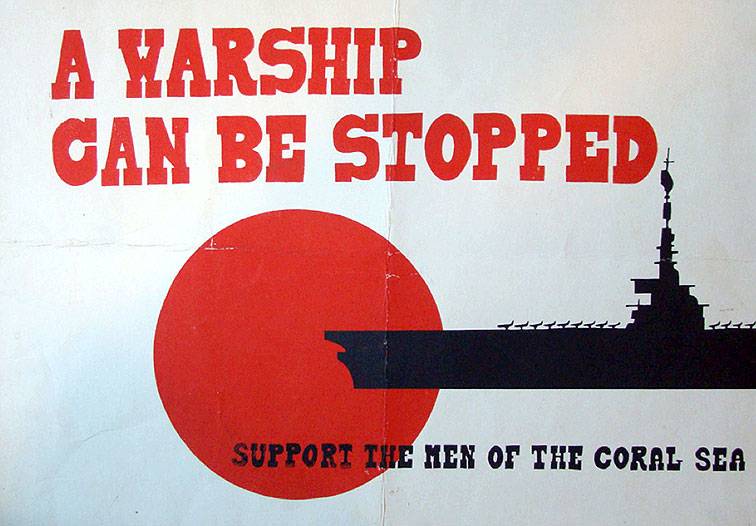

In the fall of 1971, ten churches from the San Francisco Bay Area declared themselves sanctuaries for sailors from the USS Coral Sea, an aircraft carrier harbored at the Alameda Naval Yard awaiting deployment to Vietnam, and the target of a massive antiwar organizing campaign. As a gesture of support for the congregations and servicemen who were torn between their military duty and their conscience, the Berkeley City Council took the unprecedented step of declaring the entire city a sanctuary for war resisters, providing a template for which dozens of U.S. cities would eventually model their own “City of Refuge” policies at the height of the Central American Sanctuary Movement. In October of 1971, Reverend Gus Schultz of University Lutheran Chapel was approached by seminary graduate and photojournalist Bob Fitch. Fitch had just arrived from San Diego, where he had been pivotal in organizing an effort to support war resisters from the USS Constitution, eighteen of whom had sought council and protection in a local Roman Catholic Church, referring to their actions as “sanctuary.” [29] Fitch proposed that Reverend Schultz and his congregation publically declare sanctuary for a second group of sailors from the Coral Sea, many of whom were furiously organizing a campaign entitled “Stop Our Ship” (SOS), aimed at preventing the aircraft carrier from deploying to Vietnam. [30]

1971 poster in support of the ‘Stop Our Ship’ campaign

SOURCE: http://quirkyberkeley.com/red-sun-rising-posters/

Reverend Schultz, in turn, brought the proposal to his weekly Lectionary group, a small, multi-denominational community of progressive Berkeley clergy, who met each Tuesday morning for Bible study, and whose core membership—Gus Schultz, Marilyn Chilcote, Bob McKenzie, Bill O’Donnell, Ron Parker, and Phil Getchell—would go on to organize the City’s first five Central American sanctuary churches. [31] Together with Bob Fitch and a few local attorneys, Gus and the Lectionary group devised a vision of sanctuary as “a place where people could go to consider options and create new ones without the threat of intimidation by the powers that be, parents, military, police, whoever.” [32] Undergirding this vision was the fundamental notion of informed consent and an understanding that “whoever takes the consequences makes the decision,” principles which would apply both to soldiers seeking council on the decision to go AWOL and to congregations mulling the choice to declare sanctuary. [33] In each case, their job as clergy, the Lectionary group concluded, would be to provide as open and honest an accounting of the risks and rewards involved as possible, and then to guide the stakeholders through making an empowered decision. Following a thorough educational process, congregations which voted to declare sanctuary could do so by drafting a written covenant, while those who were not ready to accept this risk could provide support at whatever level the congregation felt capable. [34] Putting theory into practice, the group had soon assembled an alliance of ten Bay Area churches ready to make public declarations of sanctuary. [35] On November 9, 1971, in a scene strikingly reminiscent of the birth of the East Bay Sanctuary Covenant a decade later, Shultz, his fellow ministers, and five sailors held a press conference in a church basement, drawing substantial media attention and garnering support from a broad cross-section of the peace movement, including singer Joan Baez and Catholic Worker Dorothy Day. [36]

The following day, in an unprecedented extension of church-based ‘sanctuary’ to the secular realm, the Berkeley City Council voted 6-1 to support a measure declaring Berkeley itself a refuge for “‘any person who is unwilling to participate in military action.” [37] The resolution, which expressed support for the congregations and the soldiers who refused to serve and offered access to city facilities to support their efforts, was particularly noteworthy for its fifth provision, declaring “‘[t]hat no Berkeley City Employee will violate the established sanctuaries by assisting in investigation, public or clandestine, of, or engaging in or assisting arrests for violation of federal laws relating to military service on the premises offering sanctuary, or by refusing established public services.” [38] This measure, with its prohibition on local cooperation with federal efforts to enforce unjust laws, would directly lay the groundwork for the city sanctuary policies of the 1980s.

Ultimately, after receiving counsel from the congregations, none of the Coral Sea sailors elected to desert. [39] However, by end of the Vietnam War, some twenty-eight Bay Area churches had either declared sanctuary or offered support to sanctuary congregations, and more than 200 serviceman had sought counseling and assistance, with issues ranging from drug addition to family issues to the decision to go AWOL. Of these, sixteen soldiers ultimately emerged as genuine candidates for sanctuary, and with the aid of the church sanctuary committees, were able to negotiate discharges as conscientious objectors. [40]

For the congregations and individuals involved, the experience of declaring sanctuary for the Coral Sea sailors primed the participants, who even then began to contemplate additional applications of the sanctuary model. [41] As Reverend Schultz would later observe, for those involved in the painstaking educational and decision-making processes that preceded the public declarations of sanctuary, this commitment proved to be “‘not an event, but a process. . . . It's kind of like Baptism. You don't get rid of it. It's always there and when the time comes that it's needed . . . you just proceeded with it. And you didn't have to reinvent it, like the wheel.” [42] Indeed, many of these same churches would go on to play pivotal roles in the Central American Sanctuary Movement, following a nearly identical process from that developed in 1971.

The Impact and Legacy of the Central American Sanctuary Movement

While it can be difficult to quantify the impact of a decentralized, grassroots effort such as the Central American Sanctuary Movement, some estimates indicate that as many as 3,000 refugees received direct assistance from sanctuary congregations between 1980 and 1992. [43] For the more than 200 American congregations that formally declared sanctuary, participation in the movement did not lead to a decrease in membership, as many had predicted. Rather, sanctuary churches frequently grew, attracting back many people “looking for a place where faithfulness meant something.” [44] Beyond these achievements, the sanctuary movement also resulted in widespread public education and saw the creation of enduring relationships between American and Central American religious communities. [45]

For Berkeley’s original sanctuary congregations, the commitment that began in 1971 with the sailors of the Coral Sea continues to this day. As Reverend Schultz would later observe, the use of sanctuary as a tactic would ebb and flow over time, developing “a life of its own. Some did sanctuary for military personnel. There was sanctuary for refugees. There was some more conservative sanctuary and more radical Sanctuary. ... [I]t would grow and then, kind of collapse for a time. And then something would happen. The Persian Gulf was invaded and the churches would renew our offer of sanctuary.” [46] University Lutheran Chapel (ULC), for example, extended and reaffirmed its original 1971 Sanctuary Covenant several times over the years, both for soldiers and asylum seekers. In the early 1990s, during the Persian Gulf War, ULC renewed its covenant and welcomed conscientious objector Leanne Mobile to take sanctuary in the chapel. [47] Similarly, several East Bay congregations that were active in the Central American Sanctuary Movement of the 1980s would go on to invoke the same tactic for Haitian refugees during the 1990s, led by Father Bill O’Donnell of Berkeley’s St. Joseph the Worker. [48] In March 2006, in response to a surge in anti-immigrant legislation, ULC’s covenant of sanctuary was revised and reaffirmed once again. [49]

ULC Rev. Gus Schultz welcomes deposed Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide to Berkeley in 1994.

Photo: http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3t1nf1gc

The East Bay Sanctuary Covenant (EBSC) also lives on as a critical resource, serving thousands of immigrants and refugees each year from its offices at the Trinity Methodist Church. EBSC’s Community Development and Education Program director, Manuel De Paz, who himself fled El Salvador in 1990 after the brutal murder of his siblings and received aid and help attaining US citizenship from EBSC, today assists dozens of people each day with tasks including learning English, finding housing, and filing for workers’ compensation. [50] EBSC’s clients include Mexicans and Central Americans, Ethiopians, South Asians, and Eritreans—many, if not most, of whom came to the Bay Area fleeing violence and abuse in their home countries. [51] In addition to providing a variety of services for more than fifty walk-ins each day, EBSC offers free, ongoing legal aid for hundreds of asylum seekers annually, thanks to approximately 100 pro bono volunteers from Bay Area law schools including UC Berkeley’s Boalt Hall. [52] In 2016, EBSC worked with approximately 700 clients, including 200 unaccompanied minors, who were seeking refuge in the United States. [53]

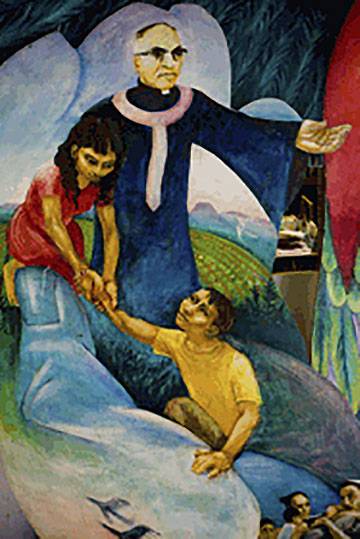

A mural featuring Archbishop Oscar Romero welcomes visitors to the EBSC office.

Photo: Sharon Abercrombie, “Refugees Find Sanctuary in Berkeley,” The Catholic Voice, May 21, 2007.

At the city level, Berkeley’s “City of Refuge” status has likewise endured, with an impact that has proven both symbolic and pragmatic. In 2007, following the deportation of a family from the Berkeley Unified School District, the Berkeley City Council voted to formally reaffirm the city’s sanctuary policy. [54] Four years later, the city refused to participate in Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s “Secure Communities” program, which would have required Berkeley law enforcement to assist in detaining undocumented immigrants. [55] City officials and immigrant rights advocates agree that Berkeley’s status as a sanctuary city has been a proven success. In addition to providing a critical safety net for undocumented immigrants and asylum seekers, offering families like EBSC’s clients substantial relief from the daily fear of arrest and deportation, the policy has proven beneficial for the community as a whole. As City Councilman Kriss Worthington notes, Berkeley’s City of Refuge law has not only served as a powerful statement in support of comprehensive immigration reform, but on a more concrete level, has successfully “enabled undocumented residents to come forward as witnesses in criminal investigations without fear of deportation.” [56]

Sanctuary Today: An Ongoing Commitment

In 2014, in response to a surge in immigration from Central America, rising deportations, and a frightening escalation in xenophobic, anti-immigrant rhetoric, many of the original cadre of sanctuary congregations around the nation and in the Bay Area formally renewed their participation in sanctuary, dubbing themselves the “New Sanctuary Movement.” [57] While the sanctuary movement of the 1980s successfully challenged deportations in the short term, today “the ravages of war, and failed domestic and international economic and trade policies—many of them fashioned in the United States—have forced a whole new wave of political and economic refugees to search for safe haven” in the United States. [58]

In the face of a worsening refugee crisis and a growing climate of hostility toward immigrants and sanctuary advocates alike, Berkeley city officials and faith communities have recommitted themselves to the New Sanctuary Movement. As current pastor of University Lutheran Chapel (ULC), Jeff Johnson, lamented in June of 2016, “‘We live in perilous times—when national leaders advocate openly about building walls and barring whole populations from entry into the U.S. … It is a time of increased xenophobia, where refugees are derided, scapegoated, and blamed. For communities of faith, action in the present moment is imperative.” [59] As a gesture of this commitment, ULC began renovations that summer to transform an unused office space into a one-bedroom apartment, becoming the first congregation in Berkeley to offer its own designated residence for refugees at risk of deportation. [60] The project, which was initiated with the support of at least a dozen local congregations, was formally unveiled in July 2016, and will be made available to an individual or family who requests safe haven within the chapel, with preference given toward those for whom deportation would involve tearing a family apart. [61] Reaffirming its own commitment to defending immigrants and those who advocate for them, on June 28, 2016, the Berkeley City Council offered unanimous support for what Councilman Kriss Worthington commended as ULC’s “‘compassionate and courageous actions.’” [62]

Sanctuary apartment at University Lutheran Chapel, 2016.

Photo: Tracey Taylor, “Local Church Offers Sanctuary to Those Facing Deportation,” Berkeleyside, 24 July 2016.

The election of anti-immigrant President Donald Trump in November 2016 ushered in a new phase of the sanctuary movement, the history of which is unfolding at the time of this writing. Immigrants and activists have reacted to Trump’s unexpected victory with both deep fear and bold defiance. Despite the President’s threats to condition all federal funding on cooperation with federal immigration authorities, cities of refuge across the Bay Area and across the country have raced to publicly reaffirm their commitments to sanctuary. [63] Officials in Berkeley—a city which stands to lose some $11.5 million in federal funds in the proposed crackdown on sanctuary localities—have vowed not to buckle to pressure from the incoming administration. Upon Trump’s election, Mayor Jesse Arreguin pledged that Berkeley “‘will remain a beacon of light during this dark time,’” assuring residents that “‘[f]rom hard-working families in our neighborhoods to Dreamers in our classrooms, our city will be a safe space.’” [64]

Notes

[1] Original Covenant of Sanctuary, East Bay Sanctuary Covenant, Rpt. in Susan B. Coutin, The Culture of Protest: Religious Activism and the U.S. Sanctuary Movement (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1993), 230.

[2] Robert Tomsho, The American Sanctuary Movement (Austin, TX: Texas Monthly, 1987), 30.

[3] Tomsho, American Sanctuary Movement, 30.

[4] Text of EBSC Original Covenant of Sanctuary (Coutin, Culture of Protest, 230):

“The Bay Area has become a place of uncertain refuge for men, women and children who are fleeing for their lives from the vicious and devastating conflict in Central America. Many of these refugees have chosen to leave their country only after witnessing the murder of close friends and relatives.

The United Nations has declared these people legitimate refugees of war; by every moral and legal standard, they ought to be received as such by the government of the United States. The 1951 United Nations Convention and the 1967 Protocol Agreements on refugees—both signed by the U.S.—established the rights of refugees not to be sent back to their countries of origin. Thus far, however, our government has been unwilling to meet it’s [sic] obligations under these agreements. The refugees among us are consequently threatened with the prospect of deportation back to El Salvador and Guatemala, where they face the likelihood of severe reprisals, perhaps including death.

This is not the first time religious people have been called to bear witness to our faith in providing sanctuary to refugees branded “illegal” in their flight from persecution. The slaves also fled north in our own country and the Jews who fled Nazi Germany are but two examples from recent history. We believe the religious community is now being called again to provide sanctuary to the refugees among us.

Therefore, we join in covenant to provide sanctuary—support, protection, and advocacy—to the El Salvadoran and Guatemalan refugees who request safe haven out of fear and persecution upon return to their homeland. We do this out of concern for the welfare of these refugees, regardless of their official immigrant status. We acknowledge that legal consequences may result from out action. We enter this covenant as an act of religious commitment.”

[5] Eileen M. Purcell, Introduction, The Public Sanctuary Movement: An Historical Basis of Hope: Oral Histories (San Francisco: Sanctuary Oral History Project, 2007), 9.

[6] Bob McKenzie, interviewed by Eileen M. Purcell, transcript, Sanctuary Oral History Project, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA, January 21, 1998, 6-7.

[7] Robert McAfee Brown, "The Case for Sanctuary," transcript, Commonwealth Club, San Francisco, 20 June 1986, Graduate Theological Union Archives, 3.

[8] Marilyn Chilcote, interviewed by Eileen M. Purcell, transcript, Sanctuary Oral History Project, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA, June 30, 1998, 18-19; Coutin, Culture of Protest, 10.

[9] Randy K. Lippert and Sean Rehaag, eds, Sanctuary Practices in International Perspectives: Migration, Citizenship, and Social Movements (Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2013), 217; Coutin, Culture of Protest, 39.

[10] Vincent N. Parrillo, "Sanctuary Movement," Encyclopedia of Social Problems, Vol. 2 (Los Angeles: Sage, 2008), 799.

[11] Harriet Swift, "Bay Area Sets Pace for Refugee Sanctuary" (Oakland Tribune 22 Feb. 1985), Rpt. in The Sanctuary Movement (Oakland: Data Center, 1985), 60; Marilyn Chilcote, June 30, 1998, 18-19.

[12] Marilyn Chilcote, June 30, 1998, 19.

[13] Charles Burress, “INS Assails Berkeley’s Latin Sanctuary” (San Francisco Chronicle 21 Feb. 1985), Rpt. in The Sanctuary Movement (Oakland: Data Center, 1985), 63.

[14] Swift, “Bay Area Sets Pace,” 59-60.

[15] Bert Johnson, “Berkeley Defends Sanctuary Status.” East Bay Express, 23 Sept. 2015.

[16] Associated Press, "Berkeley Votes to Be Sanctuary for Refugees," Los Angeles Times 21 Feb. 1985.

[17] Rebecca Sainer, “Berkeley as Sanctuary: City Declares Haven for Central American Refugees” (San Jose Mercury 22 Feb. 1985), Rpt. in The Sanctuary Movement (Oakland: Data Center, 1985), 61.

[18] Associated Press, “Berkeley Votes to Be Sanctuary for Refugees;” Sainer, “Berkeley as Sanctuary,” 61.

[19] Sainer, “Berkeley as Sanctuary,” 61.

[20] Matthew Green and Jessica Tarlton, "What Are Sanctuary Cities and How Are They Bracing for Trump’s Proposed Immigration Crackdown?" The Lowdown, KQED News, 17 Nov. 2016.

[21] Lippert and Rehaag, Sanctuary Practices, 46.

[22] Peter Sammon, interviewed by Eileen M. Purcell, transcript, Sanctuary Oral History Project, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA, February 13, 1998, 10-11.

[23] Lippert and Rehaag, Sanctuary Practices, 46, 224.

[24] Johnson, “Berkeley Defends Sanctuary Status.”

[25] Green and Tarlton, “What Are Sanctuary Cities?”

[26] Ann Crittenden, Sanctuary: A Story of American Conscience and the Law in Collision (New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1988), 62.

[27] Associated Press, “Berkeley Votes to Be Sanctuary for Refugees.”

[28] Gustav Schultz, interviewed by Eileen M. Purcell, transcript, Sanctuary Oral History Project, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA, March 10, 1998, 78; Bob McKenzie, January 21, 1998, 3; Bill O’Donnell, interviewed by Eileen M. Purcell, transcript, Sanctuary Oral History Project, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA, February 5, 1998, 1, 5.

[29] Ignatius Bau, This Ground is Holy: Church Sanctuary and Central American Refugees (New York: Paulist Press, 1985), 167.

[30] Lippert and Rehaag, Sanctuary Practices, 221-222.

[31] Gustav Schultz, March 10, 1998, 86.

[32] Robert D. Fitch, interviewed by Eileen M. Purcell, transcript, Sanctuary Oral History Project, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA, March 25, 1998, 14.

[33] Rbert D. Fitch, March 25, 1998, 7.

[34] Purcell, Public Sanctuary Movement, 5-6; Robert D. Fitch, March 25, 1998, 8-10.

[35] Bau, This Ground is Holy, 168.

[36] Tomsho, American Sanctuary Movement, 28; Purcell, Public Sanctuary Movement, 5.

[37] Bau, This Ground is Holy, 168.

[38] Lippert and Rehaag, Sanctuary Practices, 223.

[39] Bau, This Ground is Holy, 168.

[40] Gustav Schultz, March 10, 1998, 83; Gustav Schultz, interviewed by Eileen M. Purcell, transcript, Sanctuary Oral History Project, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA, March 11, 1998, 91-2; Tomsho, American Sanctuary Movement, 28.

[41] Bill O’Donnell, February 5, 1998, 5; Robert D. Fitch, March 25, 1998, 15.

[42] Gustav Schultz, March 11, 1998, 93.

[43] Bau, This Ground is Holy, 12.

[44] Marilyn Chilcote, June 30, 1998, 16.

[45] Purcell, Public Sanctuary Movement, 10.

[46] Gustav Schultz, March 10, 1998, 87.

[47] Gustav Schultz, March 11, 1998, 92.

[48] Bill O’Donnell, February 5, 1998, 9; Coutin, Culture of Protest, 229.

[49] Purcell, Public Sanctuary Movement, 6.

[50] Brenna Smith, "Interfaith Organizations in Berkeley Welcome World’s Refugees," The Daily Californian, 22 July 2015.

[51] Smith, “Interfaith Organizations in Berkeley;” Sharon Abercrombie, “Refugees Find Sanctuary in Berkeley,” The Catholic Voice, May 21, 2007.

[52] Abercrombie, “Refugees Find Sanctuary in Berkeley.”

[53] Smith, “Interfaith Organizations in Berkeley.”

[54] Cassandra Vogel, “Undocumented Immigrants Face Uncertainty in Wake of Trump’s Election,” The Daily Californian, 28 Nov. 2016.

[55] Vogel, “Undocumented Immigrants Face Uncertainty.”

[56] Johnson, “Berkeley Defends Sanctuary Status.”

[57] Stephen Stock, David Paredes, and Scott Pham, "Sanctuary for Immigrants Comes Back to the Bay Area," NBC Bay Area, 24 Nov. 2014.

[58] Purcell, Public Sanctuary Movement, 4.

[59] Tracey Taylor, “Local Church Offers Sanctuary to Those Facing Deportation,” Berkeleyside, 24 July 2016.

[60] Lillian Dong, "Local Berkeley Chapel Offers Place of Sanctuary for Immigrants," The Daily Californian, 24 July 2015.

[61] Taylor, “Local Church Offers Sanctuary.”

[62] Dong, “Local Berkeley Chapel.”

[63] Green and Tarlton, “What Are Sanctuary Cities?”

[64] Tom Lochner, "Berkeley to Remain ‘Sanctuary City,’ Says Mayor Elect," East Bay Times, 25 Nov. 2016.