Project One: Pueblo in the City

Historical Essay

by Charles Raisch

Originally published in the May 1976 issue of Mother Jones magazine. Reprinted with permission.

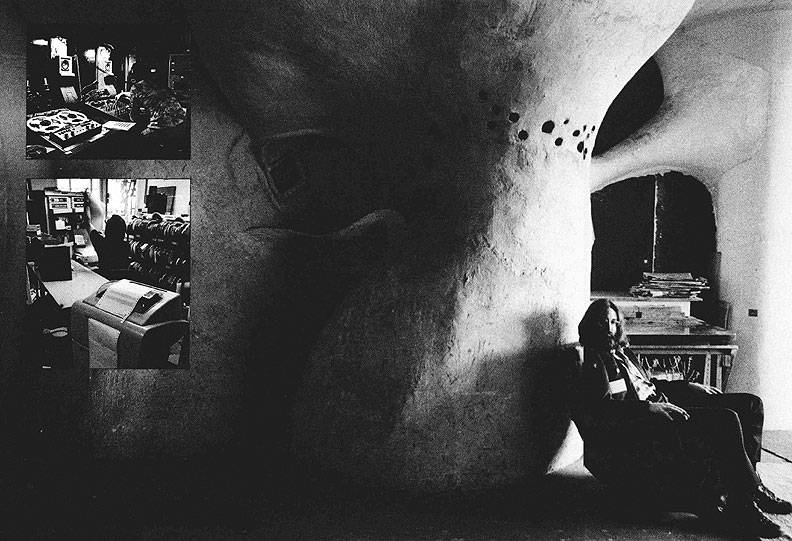

Project One recording studio, the original SDS-940 computer, and a sculptured wall.

Photo by R. Valentine Atkinson

The former candy factory that housed Project One from 1971-1980, seen here in 2017.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Pam has a vice president of Bank of America on hold while she rattles off tax exemption percentages to a top public relations executive of the Transamerica Corporation. The tall, thin woman digs her nails into her palms; the skin whitens like thin ice with air underneath. She alternates between forced carefreeness and total assertiveness as she negotiates.

"Listen, Bob," she says, "if the old man okays this, your subsidiary claims a million-dollar tax exemption. The Xerox SDS-940 has a market value of only $150,000; in a year, it will have no market value at all. Give it to us and you've got good copy for your next stockholders' meeting. The papers are ready, Bob. All we need is his signature."

Near Pam, long-haired, unshaven, drop-out computer freaks sit in a circle of ten or so—dark figures on the crazyquilt carpeted floor in a cold basement room in Project One, the warehouse commune in San Francisco's South of Market industrial district. They listen intently to the phone talk. Pam is going all the way this time. They meditate on every word, nod to one another, chain smoke and drink beer out of quart bottles. “Give us that goddam computer,” someone says under his breath.

And Omigod, when the computer finally arrives, is it big and whirring, like an outer space tractor-trailer with beeps, lights and everything but Mr. Spock's pointed ears mirrored in the shiny knobs. And here's about 30 long-haired freaks loading ol' SDS-940 into the One commune warehouse, stepping over empty pint bottles of port. Big grey shapes of metal, like angular sculpture, roll in through the front lobby one piece at a time, past the methadone clinic, back on dollies with ten, 20, 30 hands pushing, pulling, holding, guiding and finally, behind a dustless, airtight glass house, plugging it in! One high time. A party forms as it's assembled. Ralph, Paul, Steve, Wilma, Mary and Pam herself, beaming high. A keg of beer is tapped and sits on the disc memory bank console. Joints float around outside the glass room. There she whirrs! It's ours. Holy technological revolutionaries. Political power comes out of the barrel of a rolled-up computer print-out sheet. It's ours.

Project One is in an old converted candy factory built in the '20s. It is painted screaming mustard yellow and occupies almost a city block. It has five stories with large windows. There are lots of plants in those windows: coleus, fern, avocado, geranium, Aloe vera and scads of ivy. Behind the door simply marked One in large painted letters, a maze of stairwells, hallways and secret passages begins. The 84,000 square-foot warehouse has been divided up and converted into 60 huge work studios, or big communal apartments called spaces. The inside of One is painted like A Clockwork Orange set with endless orange, blue, crimson, rainbow-splashed hallways and stairwells. There is more than a mile of psychedelically-colored walkways. There are flowing sculptured walls that weave in and out, whole cement sculptured apartments and multi-functional group baths and showers with tilework and cut glass windows. There's a 20-foot-wide nautilus spa in which you can luxuriate. There are counter-balanced false walls that swing out, revealing an entry into an apartment complex at the touch of a finger. Project One is an internal village, a high technology pueblo, right in the middle of San Francisco.

Symbolically, the computer formed the core of the Project One community. SDS-940 became a free-access community computer for northern California. Project One's computer freaks now use it to do typesetting, research, mailing and bookkeeping for Amnesty International, Tenants' Action League, La Raza en Acción (a statewide Chicano organization) and many other groups.

Four years ago, when it came to One, the computer set the tone for the type of people who would be admitted.

No lazy hippies allowed. No welfare types, no people who just wanted to stay stoned all the time. No students looking for a dormitory. No artists or theater people, or wackies in any form, unless they were really into building a community and could prove it to the general meeting. One has changed of late, and is no longer the technological utopia its founders once thought it to be. But in the beginning, during the early years, One was a place to work, change your life and build a new community.

Ralph Scott, an architect and engineer who studied with Buckminster Fuller, originated the concept of One after a minor nervous breakdown in the spring of 1970. At the time, he lived with a group of friends in a small warehouse loft. The more he talked with others about the idea of a warehouse community ecosystem, the bigger it grew, until a formal proposal and a rough budget had been written and a large group of people organized. Eventually a group of about 100 people put down first and last months' rent on a five-year lease. Monthly rent was $4,200; utilities were another $1,000. The first day, people pitched tents and parachutes and started building rooms with sheetrock walls. Early pictures of the building show no walls at all, each level a cavernous yawn of concrete extending into the distance, the floors and ceilings seeming to meet way back there in the shadows. Empty. The warehouse had been abandoned for years, with only outer walls, stairwells and pillars every 17 feet. And now, suddenly, it became a human beehive.

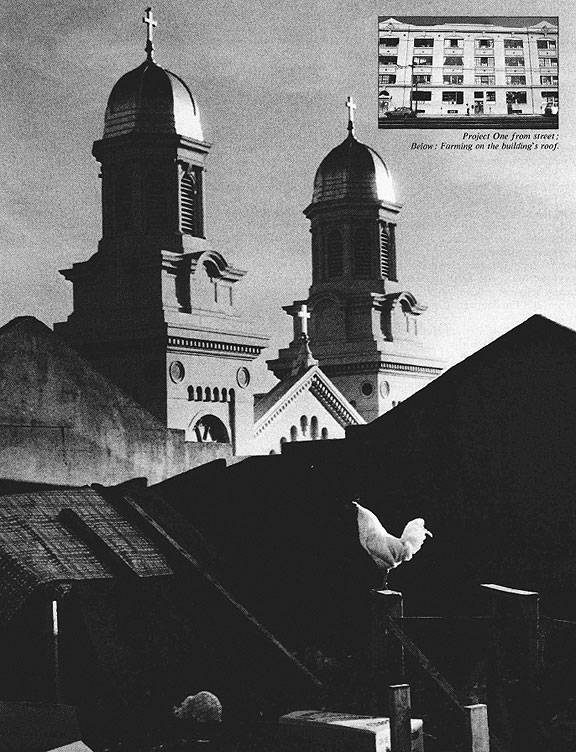

View from Project One roof towards St. Joseph's at 10th and Howard.

Photos by R. Valentine Atkinson

The work followed an erratic pattern: drive yourself until you drop, and then celebrate like hell. People who had been nailing sheetrock for 20 hours would suddenly get drunk and roar around the third floor on big Harley motorcycles. Construction ran night and day, with dozens of people working for three years straight. To a lesser degree, the building still goes on even now. People continue to flow into One: immigrants to a new country or refugees from an old one.

A whole tool-exploring community has formed in the building since One first opened its doors six years ago. Tools were scammed, demystified and made free to anyone who wanted access to them. The famous School of Holography, which has trained artists such as Salvador Dali in the newest projected, three-dimensional, laser-power figures, was born in One. Paul Widess, who had studied with Paolo Soleri, showed up, moved in, and began designing and building sculptured "soft" concrete environments. The Blossom Family (Hair! cast drop-outs) built an eight track recording studio in the basement.

In 1972 One was fully monitored from across the street by agents in one of James McCord's secret spy stations. McCord testified before the Senate Watergate Committee that his gang of secret White House agents also planted $10,000 with a Project One media organization while recording room and telephone conversation. As the coat and tie surveillance teams were changing shifts one afternoon, they were greeted by a raggedy crowd of One people with dozens of still cameras, movie cameras, lights and a video-tape Portapak team, complete with boom, following them across the street to their black sedan.

Craig and Robert, who started Symbas Experimental High School, are two of the people who formed the founding group of One. They brought dozens of high school students from New York and California into the building over a three-year period. Robert organized work squads, finally abandoning his professional role entirely and becoming a journeyman plumber.

Nina at the door of Project One, 1980.

Photo © Janet Delaney

And then there is Ray, who has probably done more to humanize and soften the building than anyone else. He is 6'3", heavily bearded: a Viking with long brown hair. With his outrageous preschool of three and four-year-olds, his nonprofit, open-air hallway produce market on Saturday mornings and his perennial open door, free soup and global political analysis, it is Ray who creates the enduring sense of family and humanist community at One. He is One's holy man, a fervent student of Tai-Chi and esoteric Chinese breathing disciplines. All his trips are big ones.

Countless other people have flowed in and out of Project One since its birth. Today the average resident population is over 80, about half male and half female, with another 200 people who come into the building for work but sleep elsewhere. One has been the home for many projects that have either bloomed or wilted with time: dance troupes and potters; the Optic Nerve Video Tape Collective; Image Works, a motion picture lab; the Health Co-op, a group of doctors, masseurs, chiropractors and herbalists; San Francisco Vietnam Veterans Against the War ; War Resisters' League; Social Services Employees' Union; the Ecology Center Press; a women's Karate academy; and Rutabaga, a collective contracting group of plumbers, painters, electricians, carpenters and bricklayers. There is a loose national network of One people, jokingly referred to as Alumni, who keep in touch in minor colonies in New York, Boston, Chicago and St. Louis. If you've lived in One, you tend to immediately feel a bond with someone else who has: it's an extended family. As a result of the One experiment, similar projects have organized elsewhere—Projects Artaud and Two in San Francisco, a barge commune in New York City and a Project One in Berlin that was sparked after a German magazine and TV program did specials on One in California.

Esme, my daughter, then two years old, and 1 applied for space in One on the fourth floor during the height of Nixon 's Christmas bombing of Cambodia in 1972. At the floor meeting where our application came up, Peter, a carpenter and artist who makes bright, mural-size paintings on heavy, laminated wood, objected. He was about 30 with short hair and no beard. "I don't even know this guy, why should I let him move onto my floor?" he said. The meeting got very quiet. Another fourth-floor resident, Shaw, spoke up for me, saying that he knew my writing, printing, photography, and other work, and that he thought I and the magazine I planned to produce would be an asset to the community. Peter then softened when he realized that I did my own printing and production and could handle real machinery in addition to a typewriter, and when he saw that my hands and fingernails were hopelessly dirty from ink and grease. Though Peter still scowled at not knowing or liking me personally, he approved of my entrance.

I got two-and-a-half bays. (A bay is the space between four pillars, 17' by 17' or just shy of 300 square feet. The ceilings are concrete and 12 feet above a brick floor.) Rent, I discovered, varies every month according to the current population, and is figured in terms of a Building Maintenance Unit. A BMU is usually about $60 for one adult. You also pay a Space Rate Unit of about $17 per bay. My rent now is $125 a month. I am also required to do three hours of work each week on the Building Maintenance rotating job-assignment list. This includes mopping floors, cleaning bath rooms, front desk duty and laundry room maintenance.

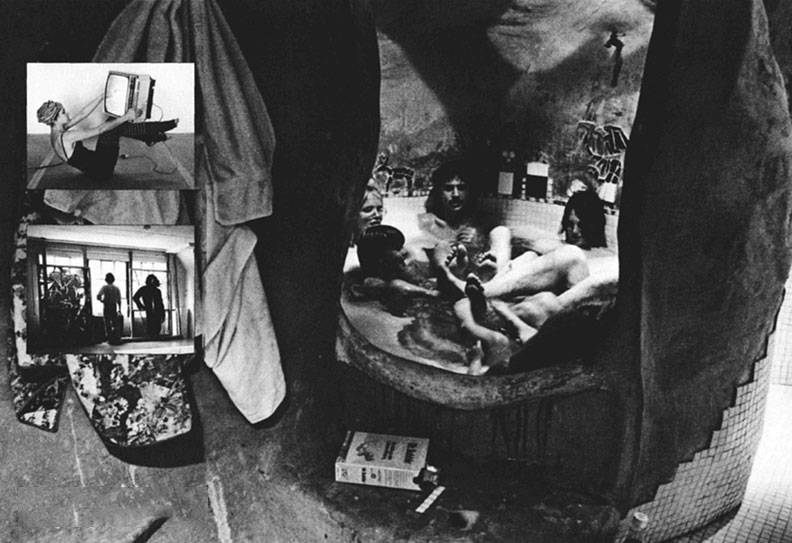

Project One interior, 1979.

Photos © by Janet Delaney

All improvements an occupant makes on a space must remain intact if attached to the walls or floors. The five members who preceded me in the creation of this space include one person w ho built the north and south walls and windows, and another who began the plumbing. I installed full wiring, the west wall and the kitchen. I built my bedroom, a Playroom and Esme's bedroom, which I enlarge every six months. Her bedroom space grows with her. Whenever I buy her a bigger coat, I also build her a bigger room; it only takes a few hours.

High ceilings, wall-size windows and a cold, rugged sense of space all around are typical of the living and working areas of One. Many of the big windows open onto a bare concrete wall 12 feet away across an alley. Some spaces have no windows at all-these so-called "dark bays" are avoided or converted. They can be lifeless, depressing places where plants and personal hopes die. There are a great many spaces that stay underdeveloped. People sometimes move in, open a few cardboard boxes and live on a foam pad in the corner. Spaces are screaming with conversion possibilities, but some must wait out their current occupant before the work is done.

Soon after I moved in, many of my new neighbors began to volunteer time, money and free materials for the magazine I was producing. On my first workday in the new space, a mysterious man dressed in coveralls and sporting a goatee walked in and asked me what I needed. "How do you envision the physical plant?" he asked me oddly. He carried himself like a factory foreman or industrial engineer, except for a two-foot braid of extremely curly brown hair. We discussed my plans. He walked in that afternoon and quietly installed full wall shelving in the editorial space as I read pasted-up copy for the next issue. That week, two light tables, three long work tables, two sinks, a double bed and a couple hundred dollars' worth of photographic equipment arrived as gifts from elsewhere in the building. I was told where to get free materials to finish my walls, plumbing and wiring, and taught to use all the tools necessary. The computer people took over the bookkeeping, accounting, billing and mailing for the magazine.

Project One, interior unit 257, 1979.

Photo © by Janet Delaney

A very loose structure governs One. There are no bosses, no standing offices, few assigned tasks and no specified responsibilities. Records, by-laws, logs, dreambooks, newsletters, tapes, giant Project One scrolls and other documents sometimes emerge from the meetings but often are lost later. Until a recent rule change, one person's objection during a vote would stop the action. An individual has as much power as the entire community. At times the meeting will turn into an encounter group. People scream, fight, slander, accuse, cry and throw chairs at one another. Meetings take place in the Penthouse, the fifth floor. Everyone dresses warm: tattered sweaters, pea-coats, shaggy leather jackets, Guatemalan short coats-there is no heat in One. The intimacy and the cold, rugged environment bring great pressure on people. Some flip out; a few have committed suicide.

General Meeting can be very harsh. When people apply for space, they are inspected. Innocent people have been raked over the coals and left emotionally shattered when One residents were pressed into giving specific reasons for objecting to the new applicants. Even though two or three people are the only ones objecting or laying this rap on you, it seems as if the rest of the 70 or so people in the room are all saying it. All these people are looking at you as you are criticized by someone you only met in a hallway, and all of them having such massively undefined power over you. The meeting has no guidelines or ethical or procedural boundaries whatsoever. Mindless vindictiveness speaks with the same force as loving guidance. The decisions at general meetings can be arbitrary; there is a whim fascism about this anarchistic government that has left many scars. Lately the meetings have been getting mellower and less critical, but the past has seen much pain.

Many times apathy will shrink the meeting's size to only 20. Sometimes there will be no meeting and the problems that should have been dealt with go ignored. The voluntary maintenance system regularly breaks down. Trash piles up on the loading dock; bathrooms get dirty; overflowed toilets go weeks without repair. Rent, posted on computer print-out sheets, often goes unpaid.

Most One people grew up during the Cold War and the space race and were schooled through the '60s to be an educated labor class. They were to fit into growing industries related to software, research and development and communications. But, as a One flyer puts it, "We were fooled in the same way the Okies were lured to California by the growers. Five jobs were promised when there was only one available. We were told that there would be an unlimited need for educated people—which was pure bullshit."

Furthermore, what jobs any of us had had were in compartmentalized office buildings, where we did not know what work went on next door or down the hall. At One, you can pop in and out of the different shops and studios and learn the skills involved; people stop in to learn from you about your work. A primary principle of the early One community was that the aura of mysticism around the world of technology exists because many people have no access to equipment or training.

One's community is based on very high-technology skills its inhabitants learned. Unlike many of the other social experiments from the counter-culture, One's survival for six years has some thing to do with its being rooted in electronic-age technological skills. Virtually all other recent intentional communities have been based on lower technologies—those of the farmer, the baker, the candlestick-maker.

Project One at play and at work, a stained glass studio, and a conceptual dance pose.

Photo by R. Valentine Atkinson

In my three years of living at One, I've learned how to use countless tools and taught others how, as well. These include the recording studio, darkroom, silkscreen shop and printing press. I have watched my hands use so many different tools that at times I couldn't answer people who asked me what I did for a living. My hands worked an arc-welder torch, 16mm camera, computer terminal keyboard, hammer, spackle knife, core driller, spark plug wrench, glass cutter. I have endured the 140-decibel bark of the diamond gun to affix 2 x 4's to the concrete for studs and wall braces; nailed sheetrock to create walls; laid steel conduit, pulling 110-volt wiring through it; installed overhead lights; sweated pipe for hot and cold water into my kitchen and darkroom; and learned the computer language ROGIRS (Resource One General Information Retrieval System).

One's reliance on high-technology skills is also a source of its limitations. A chief one is that the building has always been primarily a white, educated, middle-class society. The One people dropped out of fairly comfortable jobs and families and academic programs. They didn't run away because they had no work; they split because they couldn't stand the framework of their jobs or lives. The building inherited lots of the trappings of that class of Americans. Of the thousands of people who have passed through One, only a handful of blacks have been comfortable enough to stay around.

A leader of San Francisco's black community once attended a floor meeting at One. The group of 50 whites spent three hours trying to decide whether to lock some people's stereo equipment out of their space until they paid their rent. The black man, in his 40s, operated a small restaurant in the nearby Fillmore District, a very poor neighborhood. Finally he rose: "You people are like children arguing about toys. I can't stand to hear any more of it. There is a struggle going on in this neighborhood right now. People are organizing themselves just to get the essentials of life—a roof, a full belly, health care, a pair of shoes for their children, or their old man out of jail—while all of you sit here and play academic games with each other." He almost sputtered in disgust. "Project One is full of bullshit!" he added—and stormed out of the room.

The educated, upper-middle-class whites who dominate One's population live in an area of black, Filipino, Chicano, Native American and Catholic urban poor who are packed around the warehouses and alleys of the South of Market District and nearby ghettos. I looked around the room and realized the man's point. Most of the people in the quiet crowd will probably return to the monied suburbs on Long Island, in Connecticut or along the San Francisco Peninsula, whose commuters now tool their Pintos and station wagons every weekday along the freeways that hug One on two sides. Now, perhaps for a few years, they were playing poor.

It’s fun to live in One; that's the primary reason anyone comes. A Brecht quote once adorned a doorway at One: "Fear not death, fear rather the inadequate life." It's a free, independent life, occasionally interrupted with intense hard work. One is a great place to share work, play, dance and make friends. It's 50 of us sunbathing and barbecuing on the roof. It's massive feasts and festivals, drawing hundreds of Oners and guests into our fifth-floor Penthouse community kitchen. It's seven turkeys and four bands and a bowling lane size, makeshift banquet table with dumpster roses. It's 50 people dancing; no couples-just individuals-dancing tribal-like harvest and rain dances. It's 13 of us in a big bath, over our heads in bubbles and herbs, some of us in our 30s and 40s, and all of us giggling like children.

Throughout the United States, the cores of metropolitan areas go unused, vacant and abandoned. Since World War II the centers of American cities have rotted away. As these industrial cities change over to light service industries and away from heavy industries, the factories and warehouses become useless. You can't sell a warehouse in any major city these days; 300 stand idle in San Francisco alone, gigantic steel and concrete tools left rusting and unused. Capitalism can no longer afford organized urban factory labor; plants have been moved to suburban industrial parks, rural areas or Third World countries where labor can be purchased more cheaply.

High-technology tools are mystified and used only by a few. Those that are sold to the many are designed for consumers who will buy a band saw, or 16mm movie camera, or an 8 x 10 en larger and use it occasionally, but, most importantly, lock it up in the single family garage. Any one of the residential and suburban neighborhoods of the nation would yield street after street full of garages and basements and part-time workshops, where tools and skills for possible community sharing waste away.

A building is a tool. At its most practical level, the economics of warehouse living guarantee it a big role in the reclamation of the city. You don't have to be a disgruntled, drop-out space engineer to build a loft of 2 x 4's in a warehouse and scrape the paint off the skylight. Warehouse communities of artists, theater people and mechanics have formed their own groups for little more reason than cheap rent, something One can no longer offer. Soaring urban rents, a glutted job market, unemployment, inflation and the 50 per cent divorce rate in California continue to feed what is fast becoming a warehouse movement.

Italian artists at Project One, 1979.

Various interiors and residents at Project One, 1979.

Photos © by Janet Delaney

Functioning warehouse communities will continue to spring up, but the revolutionary spirit of their first successful model is now dying away. A mixture of things—the passing of time, rising rents, success itself—are changing One into a more settled and less exciting community. Patterns have become routines. Almost all of the great characters who were One's founders left the building in a migration period in mid-1975; they took most of One's political activism with them. Living spaces are now built; there are no more vast empty spaces to conquer with sheetrock walls. The all night general meetings are no more; the fervor has gradually wheezed out.

People come into the building now calling themselves artists or dramatists, once dirty words synonymous with laziness and "energy rip-off personalities." More and more over the last year, people apply for space in One and are no longer grilled on their responsibilities and asked the once primary question, "Why do you want to live here; what can you offer this community?" People act indignant when asked if they will improve their space, learn plumbing or mop the hall floors.

More and more profit-oriented proprietorships in the building own their tools and pay salaries to "employees." Before, virtually all organizations in the building operated collectively with non-profit status. As more non-radical middle-class people move into the community, a tendency to write a check, instead of doing the physical labor oneself, has appeared and grows steadily. Outside plumbers recently were called in to repair a space on the third floor, a symbolic and unheard-of harbinger of the death of One as a political commune. People in the building with skills now charge hourly wages of$3 and $4 for working in a neighbor's space, pulling wire or replacing windows, without training anyone. Where before violent screams of "rip-off" and "make your money outside the building!" would follow such an act, now there is no protest. Organizations headquartered on One's first floor are still a major center of social change work in northern California, but the building's residents have lost interest.

The process that created One is over. New people often apply for and receive space with no idea what is different about this building, except that it is painted wildly and very expensive compared to other warehouse space in the same neighborhood. One's newer residents consider themselves tenants of a building and not members of a communal organization. Its inhabitants, apolitical and suburban-born, have little desire to change their styles of work or living. Once a homestead, America's largest urban commune is today rapidly evolving into a dormitory. The next six years of One will not be like the last six. The new people will decide what they want and more changes will come. Not far away, Project Artaud, a gigantic warehouse of artists and theater people, operates with a salaried manager and assistant manager. This is a probable end for One. One people, never far from the world of colleges and universities anyway, reflect the same mentality as the current breed of apathetic college students. Social unrest is at rest. At One, the remarkable revolutionary history, it’s like the ’50s all over again.

Project One, 1979, several years after this article was written, when most of the spaces had been privatized and turned into specific artist studios. The infrastructure, however, was still an ongoing work in progress. Today this building houses the San Francisco Department of Parking and Traffic citation bureau!

Photo © by Janet Delaney