Warren Hinckle Speaks

Historical Essay

This interview with legendary San Francisco journalist Warren Hinckle was originally published in July 2010 on Babylon Falling and is included here with their permission.

All Photos © Kensey Lamb

On one of our very last days in San Francisco, Kensey and I spent the morning with legendary magazine publisher and award-winning journalist Warren Hinckle III at the Double Play down in the Mission. Walking in, loaded down with binders of magazines, camera equipment and with big smiles on our faces, we looked like a couple of lost tourists. I suspect that if I hadn’t slipped Warren’s name into my ginger ale order I might have been shown the door. But, as it was, the bartender poured the drink and happily pointed us in the direction of Warren’s booth, where we settled in. Arriving a few minutes later, and sensing that our presence already had the morning crowd a little restless, Warren quickly herded us to the back room.

I was there to share my collection of Ramparts and Scanlan’s to see if there was anything he wanted to scan for his book, the perennially delayed Who Killed Hunter S. Thompson: The story of the birth of Gonzo. Lavishly illustrated, the book is, at last count, clocking in at over 400 pages full of original material from many of Hunter’s friends and overflowing with ephemera…guaranteed to be a classic when it finally comes out.

As he thumbed through the magazines and showed us proofs of the book we talked about his friendship with Hunter; the roots of Gonzo journalism and the culture that spawned it; his tenure at the groundbreaking radical slick, Ramparts magazine, in the ‘60s; working with Hunter at his short-lived, but highly influential, muckraking monthly Scanlan’s; the Kennedy assassination; San Francisco’s favorite merchants of porn, The O’Farrell brothers; and much more. Enjoy!

What’s the genesis of Who Killed Hunter S. Thompson? I know it’s been delayed since 2005.

It started right after Hunter shot himself and, originally, was going to be a tribute to Hunter. I called all his friends, ones I was close to, and, you know, had to beat a few people into writing things who had never written before—like Bill Cardoso who hadn’t written a piece in 20 years and famously never gets anything completed and done. So we extracted a lot of manuscripts, and probably, within a year, kind of had a book, but it kept developing and we decided it was going to be a non-profit book. We said we’d give a prize—wouldn’t be any money, a Gonzo prize or something, god knows what the criterion for that would be. But we figured hey, we’d make a movie instead, get all these people together in a room at the Mitchell Brothers. I just kept finding stuff and thought there’s no rush because, you know, it’s [Ron] Turner’s place [Last Gasp] and he puts out art books mostly anyway, and there’s no rush on these things. And everybody’s doing other projects, and we didn’t have any staff, so we ended up producing the book, which took a lot longer. This was a massively complicated book, and so all of a sudden, we got in the middle of it and that added a year or so to it. Stuff just kept popping up, I mean really treasured stuff…underground cartoonists’ little home publications that were comic books with color covers but maybe they had a 1,500 run, little collectors run…fabulously interesting stuff about Hunter during the Mitchell Brothers period and other times. And so that became a section. Anyway, it just kept growing. And so Turner is always, “When’s it going to be done?” And I said, “Well eventually.”

We finally did a bunch of screwing around with this book. Turner will tell you that’s all I’ve been doing.

[Laughter]

It sort of makes a little more sense now: we finally have [figured out] what the book’s about…I think. It’s all this Ramparts and Scanlan’s stuff, and it’s like, “What’s that got to do with Hunter?” We sort of fit everything under Gonzo journalism in the general sense—how that stuff all started. Hunter always said Ramparts was a Gonzo magazine, and I said, “Bullshit!” You know, it was just leftie bullshit wrapped up. And he says, “No, no, no, you broke all the rules, you smashed plates, you did everything, you drove everybody nuts, it was in your face, it was Gonzo.” [The book will also have] all his faxes, his personal stuff to people in the middle of the night. You know, he always would have crazy letterheads and wrote with a big heavy felt tip pen. Wild stuff.

Anyway, now we’re going with Who Killed Hunter S. Thompson: The story of the birth of Gonzo. It takes the edge off the title. That was Turner’s idea for the title, and originally Hunter’s fans were…some of them thought it was funny, some thought it was disrespectful, but now that we have the story of Gonzo and [the] colon, there’s a reason to have all this stuff. And it’s all Hunter centered and about Hunter, but its also about the period and how it all came together.

This is the full run of Scanlan's under the editorship of Warren Hinkle. The last issue was refused by the U.S.-based printer and had to be printed in Canada. One of the articles appears here.

It sounds to me, and even just looking at some of the proofs here, that it will stand out. People who are fans of Hunter, these are the questions, the things we’re interested in.

Nobody’s done this stuff. Well, I mean, there’s this book about Ramparts now, and I did a memoir thing way back [If You Have a Lemon, Make Lemonade: An Essential Memoir of a Lunatic Decade], but all the artwork that’s in there, even up through S. Clay [Wilson], that stuff, when you see it all together you go, “Jesus, what is this stuff?”

I’ve seen Hunter’s name on the masthead of Ramparts—I think in late ’67—and was wondering if he ever wrote any articles?

No. Erroneously it has been reported that he wrote for Ramparts but he never did. We pretty quickly became friends and started talking on the phone all the time, and he was in Chicago when that whole madness went down, the riots and everything. We were always talking about projects for him to do at Ramparts. We just never quite got around to figuring which ones or anything definitive. I remember we did the Kennedy assassination issue. He called me and said, “That’s it, I…” I’m trying to put this in context: when was the moon shot?

’69? July?

Maybe it was still Ramparts or maybe that was a Scanlan’s idea. I’m trying to remember now, because he was sure the moon shot was a fake, and he wanted to go to some place in Montana where he knew they had this fake landscape. I’d have to check the dates. Anyway, at the time, we were always mulling over projects and ideas, and then Scanlan’s started. And fortunately we had plenty of money, and Hunter likes money, and so immediately boom, boom, boom this stuff went on. But of course I stuck him on the masthead right away. We just never got around to getting anything done [together at Ramparts].

Hunter S. Thompson’s name first appears on the Ramparts masthead, November 1967.

But he was a friend of yours during that time period in the late ‘60s at Ramparts?

Oh yeah. I never knew him before. He just walked into the office one night. He walks in my office says, “Yeah, I’m Hunter Thompson.” This is after the Hell’s Angels book, and I’d read it and it was terrific. So anyway, we had a couple of drinks; I know we walked up the street. This is when the Ramparts offices were on Broadway at the very end at the top of the strip. So we went up the street to have dinner and came back. I had a monkey at the time—named Henry Luce to piss off the guy at Time magazine, which did get him pissed off. (Luce found a reporter and asked him if it was true those people up there have a monkey called by my name? It made me happy.) Anyway, we get back (Hunter had thrown his knapsack on the couch in my office) and I hadn’t locked the [monkey’s] cage or something like that. The monkey had gotten out and gotten into Hunter’s knapsack. And it had a whole bunch, a lot of bottles of pills in there, and they were all over the floor but they were all empty. The monkey must have gobbled them all, well obviously he did, and he was berserk. He was just running. It was an old government building where they did scientific research (I’m sure poison gas), and they had these government-type windows on the side, and in the whole center of the space were these partitions, half wood and half glass you can’t see through. The monkey was running around the top of that thing and it had its leash on—the leash was flying! And it just turned into a completely vicious bastard. It was a sweet monkey before. It was up there for a day or so. No one was going to touch the goddamn thing; it wouldn’t stop running. And Hunter just sat there and said, “Goddamned monkey stole my pills.” It did steal his pills. I said, “Fuck you why didn’t you lock your knapsack?”

“Why should I lock my knapsack? You should have security around here.”

“Not from the monkey.”

There was the period when you were at Ramparts, and then there was Scanlan’s and Gonzo journalism and all of that stuff, but after that, in the ‘80s you were working at the Examiner with Hunter….

Oh yeah, that’s another big thing in this Hunter book. That whole Examiner period and the Mitchell Brothers period. The introduction, which is this thing I wrote, mentions everything. And it’s at least a third of the book; that’s where most of the illustrations come in, that history. But that includes the whole Mitchell Brothers period, which is not that very well-known. It’s kind of known he was the night manager of the Mitchell Brothers [O’Farrell] Theatre, but those stories are fabulous and the adventures extreme. And there’s a lot of art and photos from that period. It’s not about inside the sex business, it’s about this bizarre cultural part of San Francisco where these porn merchants were actually the Medicis of the fucking town. They were the ones really laying out money for artists and having this open place where even politicians would come to connive at night. It was like some great 19th century operation in this bizarre atmosphere of naked women running around, the shows, the constant fights with the authorities, and Diane Feinstein going crazy. It’s a wonderful period. And part of that was the Examiner at the time….

A Hearst paper…

It became a really interesting paper. It became extremely wild and crazy and liberal, and it didn’t have anything to lose because it was the second paper in a land-lock, JOA, joint operating deal where they got half the money. Anyway, the Chronicle became more and more conservative after my friend Scott Newhall, another madman—a genius—left, got kicked out because he saved the paper. So Will Hearst got it for a period of years. He became the publisher. He has a concentration span about as long as a straw, a very rapidly changing mind. Will, I know him quite well, he’s a good guy. He wanted to do the paper to have some fun, and that fit perfectly with the Mitchell Brothers cultural period, and Hunter being there and me being friends with these guys. I mean, you look back at the time and the Mitchell Brothers got very good treatment in the Examiner. Sunday Magazine spreads…“The Mitchell Brothers are home with all their kids and boxes of Wheaties.” They were friends, and the government was against them, so it was crass. It was a very funny period.

You were coming from working at the Chronicle, right?

I was then writing for the Chronicle and doing pretty well, and he [Will Hearst] stole me from them to go to the Examiner—because I didn’t care if I did stuff nationally or locally, it never made a difference to me. You’re doing journalism. Shaking up the town is just as much fun as shaking up the CIA, and I didn’t have to go out and raise $2 million a year. I got paid for a change; I didn’t have to worry about it. So naturally, I told Hunter, “Hunter, you gotta get in on this deal.”

So that whole period was extraordinarily funny, and the Hunter columns that appeared in the Examiner…it’s unthinkable that they would appear in a Hearst newspaper. They were so off the wall, so wild…getting his girlfriend a tattoo to get a column to beat the deadline, that sort of thing. “What the fuck am I going to write?” Extraordinarily funny stuff. And you know the Mitchell Brothers [O’Farrell Theatre] was his office and so was the paper, and so he’d be going back and forth. And the paper was, then, very lively.

And a good part of the period, when San Francisco was a much more interesting city than it is now, part of that blossoming of eccentricity was very 19th century almost. It was a crazy town in the 19th century, obviously, and journalism was nuts. Western journalism, in general, was nuts. And I guess you could say that western journalism was the first, some of the first, Gonzo-type journalism—all the way from people putting themselves in the stories to totally making things up to getting into gun fights. Mark Twain wrote some of the first science fiction. Hoax. Eastern newspapers did hoaxes too, moon hoaxes and stuff, but Mark Twain had one famous thing, it was in Territorial Enterprise. He had a story which everyone took to be true about a guy who walked across the desert in Nevada—got across the desert with an ice helmet. He created a helmet out of ice because it kept him from the heat and he still had water. Completely made up! And it was reported around the country in the eastern papers. But that was the type of stuff that we did. And that was the type of stuff they did then.

I always thought that what a lot of what these magazines did and a lot of what Hunter would do was a wonderful throwback to what the stuff should be. And it seems so lively and fresh because of the contemporary issues, obviously, and the contentious time in the culture. But it was visible and fun and participatory in the sense that they’d go, “What the hell!” And enjoyable and seeable, graphically and physically. The personalities involved were there on the set. They were a little outrageous, a little larger than life, but they were actually doing what they were writing about and that was true of the century before. And then there was this great desert period of American journalism and they put not only the muckraking magazines out of business, but sort of the life of the…the spirit of the publishing business then became this great centrism and boring and that sort of broke out in the ‘60s and ‘70s with these crazy magazines of Gonzo and that sort of stuff. That’s kind of petered out again now to a kind of mild version of that.

But America is all about its civilization. They’ll be teaching courses on Gonzo in journalism school—and you can’t learn how to do it. Anyway, that night manager period at the Mitchell Brothers is a serious part of the San Francisco cultural history because it takes in politics and art and crazy people and you know…it was fun to do and be there and it’s fun to read about.

At this point Warren goes to refresh his drink. When he comes back he starts to flip through the copies of Ramparts and Scanlan’s that I brought, comparing them to what he has in the proofs.

This one [Ramparts, February 1968] got the most shit. But it got these women…a bunch of them were in an uproar and there were a whole bunch of women in this issue that were left-wingers and they thought it was great. They might pose in, not fancy showing neckline clothes, but it was like a photo gallery of left-wing, hot looking left-wing, women who happened to be left-wing female leaders. And they all posed and they thought it was great. But our people, oh my god. Particularly the men, who were all pussy-whipped, you know, said, “Oh they’ve done a terrible thing,” and they’re saying this is the worst and I’m thinking, “What are you crazy? What do you think we cut the head off for? It’s a satirical point! Get it you guys!”

Warren flips through a few more issues and stops on the July 27, 1968 issue of Ramparts, which was dedicated to publishing Che Guevara’s Bolivian diaries.

Didn’t Evergreen run some of the diary six months later?

No, no they ran the CIA version—there was a little war over that. We were under restrictions. The goddamned Cubans let people in other countries publish it, but you couldn’t change a word or you couldn’t add anything, so all it is is the goddamned diaries from front to back and the illustrations that they had in the government edition of the diaries—that was it. But at the same time, the CIA got a version which they sold to an American publisher, Stein & Day, who kind of did some more pro-government, right-wing stuff, and that was a doctored version—the text was doctored for this and that propaganda point. So then it was a race to get the first one out, and the Cubans wouldn’t give copyright which was a battle because they don’t respect copyright, but I had to beat them up. I said, “No, no, you guys are gonna be fucked on this thing.” That was a lot of fun. Anyway, somehow it happened. Then it turned out they’d been lying the whole time; they said they didn’t respect copyright but they still remained a member of the goddamned International Copyright Commission. The bastards. That’s why you gotta like the Cubans.

They got style.

It doesn’t matter what kind of government…the Castro guys…I never thought they were that bad at all. It’s a trade winds country that was around a lot longer before America, and the root culture is permissive, loose, and commercial. People would stop there before they went on…and that goes way, way back. So that’s rooted in whatever that culture is. People don’t understand it’s not a garrison state because the culture wouldn’t allow that.

Flipping through the proofs, Warren gets to the section on Scanlan’s.

Thompson hated this guy [the illustrator Jim Nutt]. He hated him. He went absolutely crazy, you know. “Don’t ever illustrate a thing of mine again with that bugger…it’s the most disgusting thing.”

I remember reading about the fact that Pat Oliphant was going to be the original illustrator for the “Kentucky Derby” piece.

Hunter wanted him. Well, he was the guy from the Denver Post, but he couldn’t do it. Hunter woke him up at three in the morning and got him all pissed off…he ended up being nice about it, but he couldn’t do it. I mean, we didn’t decide to do it ‘til three or four days before, so what are you gonna do? [Ralph] Steadman popped into mind and, fortunately, he was in the United States trying to get some work. So it worked out great.

Even now this will fuck people up.

That was 1970 man. That’s black and white detail and that’s pretty…knocks you out.

I remember the first guy I talked to about printing: Laughton Kennedy. This old master printer/craftsman, he was saying he always wanted to design. He set everything by hand, short-run books of old California, people’s diaries, voyagers, you know, that stuff for the private collectors. Everything was all hand-set, perfectly done—he knew what made stuff look right. I learned a lot from that guy, but he always said what he wanted to design was a can of peas for a supermarket because he says, “I would do a simple black and white label and in Caslon it would say PEAS, and there would be a little black and white drawing of a pea.” And he says, “I tell ya, when you walk down the supermarket aisle the only can of peas you’d see would be that one.”

[laughter]

Was that back in your college days that you met Laughton Kennedy?

Yeah. I got to know him, I forget how, historical society or something. And then he had a PR business for about a year, so he did all kinds of printing. Everything I ever did, he did. He was the guy who did that issue of Ramparts where [Edward] Keating went to interview Hugh Hefner. Keating was the publisher and he still had money then, and so it was, “Oh god what’s this going to be like?” And he was so fucking embarrassing. It was just idiotic drivel coming out of the mouths of both of them. This was before [Dugald] Stermer was there, so I’m saying, “But we have to print it,” because that was Hefner, this was the publisher. They were talking about great ideas—sex and western civilization—so I came up with this idea because I didn’t want anyone to read it. I came up to Laughton Kennedy and I said, “Laughton, here’s what I’d like you to do. I’d like you to set this stuff in that hand-set English antique type, and make it as illegible as possible. Find the hardest-to-read face you have.” So it looked great and you started reading and said, “Oh fuck, that’s too hard to read,” so you got over that embarrassing part. Then we put in a foldout of that stupid Hefner looking like an idiot. So it was sort of a satire on our own article and on the Playboy foldout idea. Not too many people got the joke, but at least our people did, so that’s what made me happy. And that Ramparts book came out [A Bomb in Every Issue: How the Short, Unruly Life of Ramparts Magazine Changed America by Peter Richardson] and they think Stermer did that—that was a long time before Stermer got there—and I was just trying to disguise an embarrassment.

[Ed. note: Author Peter Richardson points out: “The Hefner foldout Warren mentions in this interview appeared in the September 1965 issue. Dugald Stermer joined the magazine as art director in late 1964.”]

What did you think about the Richardson book?

The thing about that book is that the guy treats [David] Horowitz as a normal human being. He [Horowitz] is one of the biggest right-wing nut sheets in the country. Horowitz charmed the guy. All the Black Panther stuff came from Horowitz. I mean, it wasn’t that big a deal at the time at Ramparts. Anyway, we defended the Black Panthers because they had a perfect right by the Constitution to carry guns in the open, and the police were openly wiping them out and it was a good, goddamned ‘60s radical thing to do—and they had every right to do it. And it’s also true that later on too much drugs and too much money…

There was also COINTELPRO…

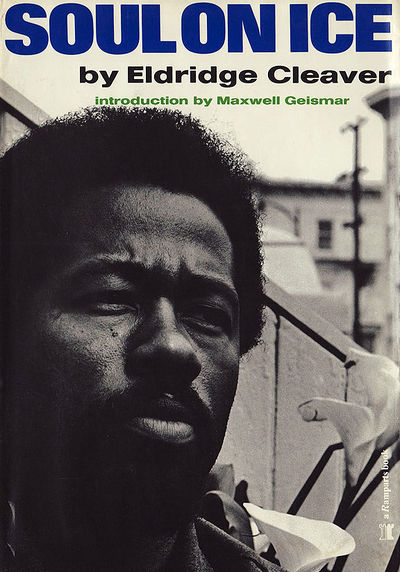

Yeah, they [the Black Panther Party] got infiltrated. The Panthers’ whole organization fell apart pretty rapidly. It was all within a period of two to three years that it all started to go down to hell in the very late ‘60s and the very bad stuff happened thereafter. But for those few years there—before Cleaver had to leave the country and he was writing the Soul On Ice letters and the Panthers were doing what they were doing—sure we defended them.

They scared the hell out of liberals, but you know they [the liberals] never had much of a backbone anyway for anything like that. The decaying Panthers of the early ‘70s—when they really went to hell—are somehow merged in history with how they started off and what they were trying to do. And you can spend a lot of time defending the Panthers, but somehow Horowitz talked him [Peter Richardson] into some goofy thing…

He just kind of missed the point there, but I don’t really want to talk shit about the guy. Oh no, Peter, hey I congratulated him. I said, man anybody that tackles that crazy operation, trying to pin down that merry-go-round for those four or five years from a distance in time is, hey, he did a pretty good job. He spent too much time with Horowitz, but other than that, the guy did a pretty good job overall.

I’m curious what the atmosphere was like in the Ramparts office. I know you famously worked way into the night on the issues….

Yeah, well you have to understand the thing didn’t have any money and it was growing enormously at the same time. I’ve read histories of Life magazine when it took off, and [Henry] Luce almost went under. He had Time going but Life got so successful—it got so big all of sudden—he had to get capitalization for it, to handle the growth and success. But he could go to protestant bankers (and god knows what). Ramparts (not that it became as big as Life magazine) had the same sort of explosion, and you know, all of a sudden, the publisher says, “I haven’t got any money anymore.” And we’d already started it—hired people, magazines were coming out and shipping, and we had to go off and try to raise money and didn’t know anything about raising money. I read a book about it with the guy who was the accountant: “This is how you raise money for a magazine.” We didn’t know shit. And it became a mad thing. Maybe two weeks out of four, sometimes almost three, we spent on running around the country, mostly to get just enough money to get the next issue out and keep the thing alive, keep it going.

So we decided on an issue, this is the cover, this and that, and you’d come back, and it’s four or five days before it has to go to press, and it wasn’t perfect and you’d say, “Fuck this. Ok, everybody here, we’re up all night. We’re gonna change this thing. It’s just not that good yet.” You know, and they’d be screaming. I mean, that’s true. I’m not apologizing for it, that’s just the way it was. What are you gonna do? I’m not going to put out some crappy issue. And if something came in at the last minute and we decided to change it at the last minute because it had more political impact or would sell better, I wasn’t going to wait a month and have somebody else get that story or twist it another way where it would have much less impact. So you know, we took shots. Those shots cost money, you know. We’d air freight issues to the newsstands. Good grief. It was reckless eccentric publishing, but it was a reckless eccentric publication in a reckless eccentric time. And you read all these guys and they’re judging it by the standards of some magazine that has Time/Life financing or something like that. We didn’t have 300 people working for us to calmly put it out and market it and sell it. Everything at once. It was nuts.

Ramparts, November 1966.

As we’re talking about this I’m thinking of the fake review of the imaginary book, Time of Assassins [by G.K. Leboeuf] in the big JFK assassination issue…

Everyone was knocking the Ramparts conspiracy things. [Robert] Scheer was never big on that stuff, having all these conspiracy guys around…

It was a whole army.

Oh yeah, they weren’t very happy because they had been working for a year on this perfect theory of the third bullet, and that sort of thing, and had it footnoted and everything. It was a huge cottage industry, and they were serious as hell. They all had their intramural feuds—it was great to watch this stuff. So this was supposed to be the big issue. Then I heard about this guy [William Penn Jones]—a little editor down in Texas who had found everybody, all these people who had died [that were] connected to the Warren Commission—and went down to see him and he was the genuine item. He had this stuff, you know. So I told Bill Turner—the FBI guy who was working for us and [who] became a good friend of mine (we did a couple books together in subsequent years)—I said lets just make sure all these motherfuckers are dead. And they were! And that really upset the spooks because that was supposed to be their issue and they were working all year on it. At the last minute I figured we’re gonna hold that stuff and we’re gonna put this wild cover on with that story.

It broke a lot of stuff open because Mark Lane had his books out and they weren’t treated in any way seriously—even though they made a lot of sales and got on lists. The New York Times, the networks, nobody would treat this stuff. Crazy people sell books, but that’s the category it was in. And that story, of all these people being dead connected to the Kennedy assassination, got the networks going and both networks got into it. Walter Cronkite got into it and he came out, [Chet] Huntley and [David] Brinkley were the big guys at NBC then, and they were out at Ramparts for two days. They all went to Texas, and, all of a sudden, it became a sort of mainstream discussion. Not that it wasn’t a national discussion before, but it broke it open to a much wider conversation, it was almost a conspiracy niche before, it wasn’t taken seriously. So it worked, but it pissed off the researchers.

Satirical review of the non-existent book, Time of Assassins by G.K. Leboeuf, about the Kennedy Assassination.

So, of course, this satirical review came in and it was obviously a phony but it was very funny because it was making fun of the spooks. So I thought, lets put that in [the issue] so we don’t look too boring. God almighty, it was 70 pages of this stuff. It’s not that it wasn’t right or it wasn’t solid, it was just BORING. And [later] it was the Boston Globe that wrote a story knocking Ramparts for its endorsement of conspiracy theories of the Kennedy assassination. And that article said we [at Ramparts] are so crazy, “but on the other hand, there are some responsible critics, among them G.K. Leboeuf.” Who could believe that? The fucking Boston Globe.

No due diligence at all.

None! The only place that G.K. Leboeuf ever existed was a phony book review in Ramparts. They [the Boston Globe] said, “There are some responsible critics…” That was a great article. That did happen.

Ramparts, for all its so-called recklessness, never got sued, was always right, and never had to take anything back, never got caught in a hoax as such—except the hoaxes it pulled on itself, because sometimes you get a little too earnest in this business, and you gotta lay back and make fun of yourself. But we never got into trouble. We could’ve put our foot into it big, considering they were trying to make us put our foot into it big. It was just old fashioned, shoe leather journalistic practices applied to left-wing theory. The only magazine that ever came close to the overall interest was the New Masses in the ‘20s and ‘30s, which was a beautiful magazine. That was a great magazine. They were totally right on on the issues, but it was really a left-wing magazine written to a left-wing audience only. The thing that Ramparts did that was different, was that it went to the mainstream.

Can you talk a little about the PR guy, Marc Stone?

[He is] Izzy Stone and Judy Stone’s (my old friend from the [San Francisco] Chronicle) brother. Yeah, Marc, he was a sweetheart, a bundle of energy and nerves. I mean he’s a conservative leftie from the PM [Picture Magazine] period, which was a big left-wing daily in the ‘40s and ‘50s in New York. These old Reds are very conservative in their lifestyles and their approaches to things—they just are. Old lefties are conservative, so I was always driving him absolutely berserk. On the other hand, he was a very energetic and effective PR guy. He really worked hard, and he was extremely helpful; not all these stories just broke automatically in the [New York] Times or other papers. We pushed the stuff and Marc did a lot of the pushing and he did it well. He was like, “Ya reckless kids, crazy kids, you’re crazy.” The left just isn’t used to spending money either. They don’t understand that.

They get nervous around it.

Yeah, totally nervous. Culturally divided. Then there was the left divide, which is another stylistic divide. The moralism of some of the left guys just drove me nuts. I remember, I think Keating, Paul Jacobs, and myself were the only guys who signed and put up our houses and stuff like that for bail or right-of-return for Cleaver, when Eldridge wanted to come back to the country. And he had turned kinda goofy by then, he was off on his run, but the left was saying no let him rot, let him be arrested and thrown in jail. And I’m saying well wait a minute, we were backing these guys who were doing entirely legitimate things. It was government set-ups. Now, because the guy changes his politics, you wanna say fuck him and put him away? I couldn’t understand that sort of moralism.

New Orleans District Attorney, Jim Garrison, on the cover of Ramparts, January 1968.

There’s a great quote in your book about not trusting these missionaries who would boil the baby to cleanse the bathwater. You were describing why you were drawn to Jim Garrison specifically. He was a madman!

One of the reasons I bring up Jim Garrison is because as I read more about Garrison I see the parallels with Hunter. Then there were also a couple quotes about some of the people that were in your life, and it seems like there’s a similar vein that runs through….people like Conrad Lynn…. They’re Lunatics! You gotta love lunatics…lunatics who are right. Lunatics who are doing, in the general sense, god’s work, right? But they’re crazy people, all kinds of personal faults and excesses and they’re fine, and they’re fun….rabid, crazy fun. Why wouldn’t you like them?

Thanks Warren!

If you’ve made it to this point I’m convinced that you will love Warren Hinckle’s memoir, If You Have a Lemon, Make Lemonade: An Essential Memoir of a Lunatic Decade. If you come across it, pick it up—you won’t be sorry.