Henry Cogswell and His Monuments

Historical Essay

by Gloria Lenhart, originally published in The Semaphore #203, Summer 2013

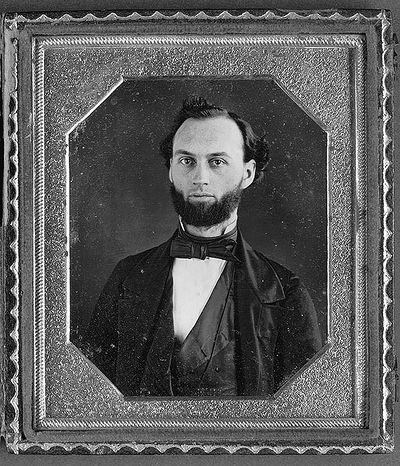

Dr. Henry Cogswell.

Photo: Bancroft Library

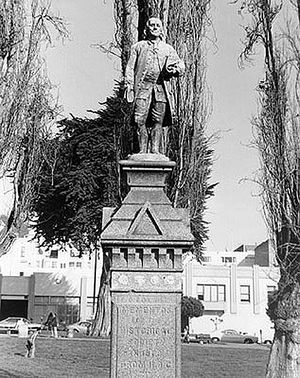

Why is there a monument dedicated to temperance topped with Benjamin Franklin in the middle of Washington Square?

The Ben Franklin temperance monument didn’t start out in Washington Square.

It was installed in 1879 at the corner of Columbus and Kearny, where the Zoetrope building now stands. It was moved to Washington Square in 1904. The city probably would have gotten rid of it altogether, except for the likeness of Ben standing on top. Instead, it was banished to an out-of the-way park that the Chronicle at the time dismissed as “where mostly the children of San Francisco’s Latin Quarter play.”

Benjamin Franklin in Washington Square.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Ben’s monument was the first of eight granite-and-bronze drinking fountains that Henry David Cogswell — millionaire dentist, ’49er and real-estate magnate — would donate to San Francisco in the 1880s. Only three of these fountains were installed and all but the one now in Washington Square were removed within a few years. Objections to the new fountains were raised because they were topped with a figure that looked a lot like Dr. Cogswell himself. The doctor insisted that his intention was only to portray an ideal man, and any resemblance was purely coincidental.

San Francisco wasn’t the only city to accept Cogswell’s generosity. Cogswell donated similar drinking fountains, also topped with his likeness, to Boston, Buffalo and Rochester, N.Y., and a dozen other eastern cities. Most are long gone, although Cogswell monuments still stand in New York City and Pawtucket, R.I. In Washington, D.C., the Cogswell monument near the National Archives inspired the formation of the Cogswell Society, which meets on the first Friday of every month. Its rallying cry is: “Temperance. I’ll drink to that!”

Cogswell temperance fountain in Washington, D.C.

Photo: Library of Congress, Carol Highsmith Collection

The story of Cogswell’s monuments began in 1873. That was the year that Columbus Avenue (then called Montgomery Avenue) was cut diagonally through the North Beach street grid to provide better access to the waterfront. Cogswell was an accomplished dentist who had invented a process for securing dentures and was a pioneer in the use of chloroform. But he had made his fortune through shrewd investments in real estate. He owned a large lot on Kearny Street which was cut in half when the new avenue was put in. The city paid the doctor for the land they used, but left Cogswell with a tiny triangle at the gore point of Columbus and Kearny. The lot was only 12 feet on its longest side, too small to build on, but Cogswell was determined to find some way to make money from it.

Cogswell soon had his answer. In 1875, actress Lotta Crabtree donated an ornate drinking fountain to the city, which was placed on a prominent corner downtown on Market Street, near the newly opened Palace Hotel. Lotta’s fountain immediately became a popular gathering place, inspiring Cogswell to design a fountain of his own. He had it made in Connecticut where he was from and shipped out. City water is all that ever flowed through the taps marked Vichy and Cal. Seltzer. Still a large crowd cheered the fountain when it was unveiled in May 1879.

Whether Cogswell dedicated his fountain to temperance out of commitment to the cause, or because it guaranteed a group of enthusiastic supporters for his fountain, is not known. The Chronicle called Cogswell’s fountain “that grey granite tombstone.” But Cogswell was making money from it. He installed small booths around his fountain that he rented to bootblacks and merchants. Then he put in benches and a podium, which he rented to politicians and preachers. The corner of Kearny and Columbus became known as Franklin Hall.

By then, Cogswell was approaching his 60th year and was worried about his legacy. Having no children to carry on the Cogswell name, he turned to philanthropy. He pledged to provide one fountain for every 100 saloons in San Francisco. He offered temperance fountains to any city or town that wanted them.

Brooklyn, N.Y., was the first city to remove Cogswell’s fountain amid protests. San Francisco cancelled installation of any more fountains after newspapers called for the removal of the two on public land. On New Year’s Day 1894, a group of young journalists lassoed the Cogswell statue at Market and Drumm streets and pulled it down. Later that year, the Cogswell fountain at Market, Battery and Bush streets was replaced by the Mechanics Monument, which is still there today.

The fountains were not Cogswell’s only philanthropic misstep. His offer to fund a College of Dentistry at UC Berkeley was rebuffed when Dr. Cogswell insisted the school be built on an undesirable piece of property he owned in San Francisco. He later built the Cogswell Polytechnical College to provide a practical education for boy and girls, but then sued to reclaim it from its trustees. Dr. Cogswell died at age 80 in 1900. He lies in Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland under a 70-foot-tall monument that he designed and installed 10 years before his death. Four granite figures representing faith, hope, charity and temperance stand at its four corners. Two railroad cars were needed to ship it from Connecticut.

San Francisco has one other Cogswell monument. In 1884, Mrs. Rebecca Lambert, widow of a sea captain, asked Cogswell to provide a 15-foot-high iron monument to mark a 400-acre plot overlooking the Golden Gate as a burial ground for seaman. The monument stands today on the 15th green of the Lincoln Park Golf Course.

Cogswell Seamen’s Memorial in Lincoln Park.

Photo: Gloria Lenhart

Gloria Lenhart is a tour guide for San Francisco City Guides, an amateur historian, and writes a blog on San Francisco history at www.mysfpast.com.