Education ‘Reform’ Meets Gentrification in San Francisco at City College

Historical Essay

by Marcy Rein

First published in "Power In Place," Race, Poverty & the Environment Vol. 21-1, 2016 under a Creative Commons nonprofit license. RP&E can be found online here.

The door to Edgar Torres’s office stands open on the first day of the 2016 spring semester, as it has on the first day of every semester for 14 years. “I do that for the students who get lost and need directions,” says Torres, head of the Latin American and Latino/a Studies Department at City College of San Francisco (CCSF). “I love the hustle and bustle of the first day. But today I’m sad, because it’s so quiet.”

City College students support their teachers and connect the dots at the rally supporting the April 2016 faculty strike.

© 2016 Marcy Rein

Founded in 1935, City College has long been the school for second-chance and first-generation students. Torres himself was the first in his family to go to college, and started at CCSF. “This school is dear to me because I’m the son of immigrants,” he says. “I never saw a Latino teacher till I came here.”

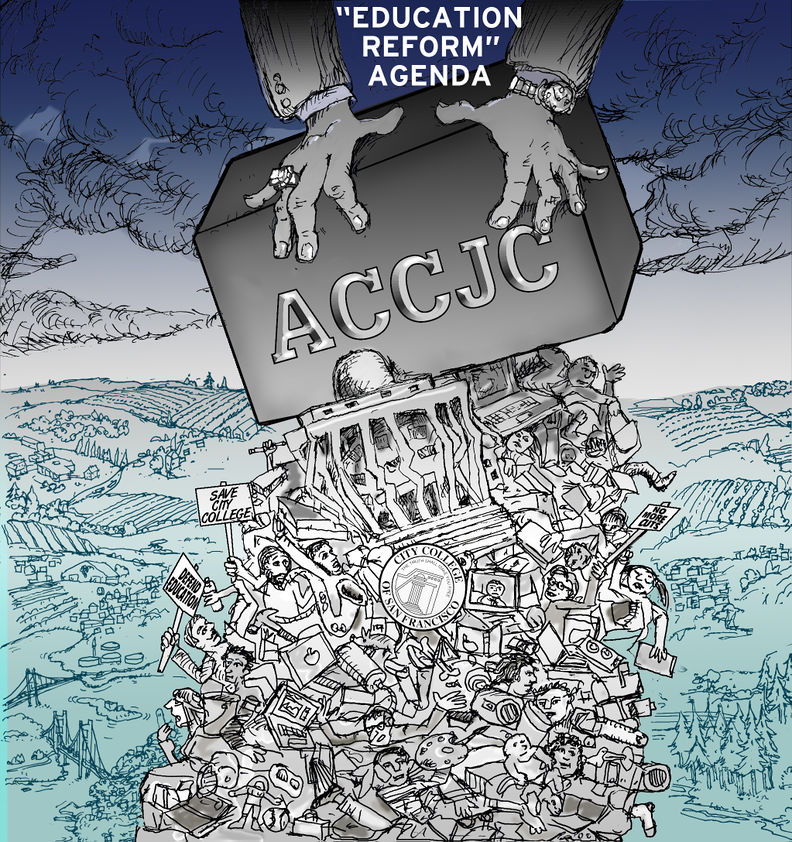

In July 2012, the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges (ACCJC) slapped City College with a “show cause” sanction, one step short of yanking its accreditation, which would have effectively shut down the school by making it ineligible for federal funding. The commission, a private body authorized by the federal government to evaluate community colleges, sanctioned City College despite the fact that academically it ranks close to the top of California’s 113 community colleges. A year later, the commission announced that CCSF would lose its accreditation, and the California Community College Board of Governors—a board appointed by the California Governor—put the school under emergency management.

But this story isn’t just about a hostile and aggressive accreditation agency. At its heart, it’s about how education “reform” and gentrification intersect and relate, and how the fight against reducing public education to corporate workforce training fits in the broader resistance to racialized displacement in San Francisco.

A Pillar of SF’s Working Class

With more than 100,000 students in 2008, City College was the largest community college in California. More than three-fourths of its students are people of color, most of them low-income or working class. The school has trained the city’s chefs, firefighters, nurses and medical technicians; taught English to some 20,000 immigrants each year; and been a home for lifelong learners needing new careers and exploring new passions.

Determined organizing by the students, the faculty and their union, and the broader community saved City College from closure, but the crisis continues. The number of students enrolled in classes has fallen to 67,000, down by a quarter from what it was before the ACCJC sanction;(1) the majority of the displaced are students of color. The workforce is shrinking, and three parcels of college property are on the real estate market, or may be soon. (See “Development for Whom?”) More than 1,200 courses have been slashed, and the administration recently announced a new 26 percent cut in classes over the next six years. Because the school receives state funding based on enrollment, this will make the downsizing permanent if it is not reversed.

“City College is a lifeline. There’s no just reason for mangling or shrinking it,” says Tarik Farrar, the chair of the African American Studies department.

Graphic © Jos Sances

Weakening the college may have been the goal all along. In K-12 public education, emergency managers have been imposed on school districts to smooth the way for charter schools, notes City College student organizer Lalo Gonzalez. “With the Special Trustee at City College, we saw the same thing,” Gonzalez says. “The threat of closure was used to force the school to implement policy changes. The accreditation process was hijacked and used as a vehicle to downsize and strip out valuable real estate,” he says.

Preview from Chicago

In Chicago, the proving ground for K-12 education “reform” and hometown of President Obama’s former education secretary Arne Duncan, the city systematically closed more than 150 public schools in gentrifying neighborhoods, destabilizing Black and Latino communities and opening privately run charter schools. In most of the closed schools, students of color made up 99 percent of the student body.(2) The charter schools filter out many English language learners and students with special needs; divert funding from traditional public schools; and haven’t delivered the academic benefits that were supposed to come from competition. They also helped make the neighborhoods more appealing to the wealthier—and whiter—new arrivals.

Chicago’s gentrification was part of its transformation into what Professor Pauline Lipman calls a “global city,” a central marketplace for finance, information innovation, and production systems.(3) The global city is highly stratified. Global capital floods its real estate market, and highly paid workers drive up prices, resulting in displacement. This description could as easily apply to today’s San Francisco, center of the tech economy, and one of the most unequal cities in the country.(4)

Education ‘Reform’ Goes to Community College

The education model developed to serve the global market emphasizes measurable standards, testing and “competence-based skills.” In K-12 it has evolved as a package of high-stakes testing, privatization schemes, and attacks on teachers and their unions; it has shaped federal education policy and roiled K-12 schools for most of the last two decades.

The Student Success Task Force, which was convened by the California Community College Chancellor’s Office in 2009, and chaired by a former president of ACCJC, adapted this project for California’s community colleges. Taken together, its recommendations aimed to tailor the colleges’ work to better meet industry needs by focusing on narrow workforce training, basic skills, and transfer to four-year schools; instituting new, more quantitative “student learning outcomes;” and emphasizing “productivity.”

The Task Force recommendations were rolled into the Student Success Act, S.B. 1456, passed by the California legislature in 2012. Supporters of the bill—including the ACCJC, which lobbied hard for it—applauded the measure’s potential to bolster student college completion rates and the California economy. Critics, with CCSF in the lead, charged that it would effectively end the open access promised by California’s 1960 Master Plan for Higher Education.

City College’s Academic Senate, Board of Trustees, student government, and chancellor spoke out against the act; the school’s award-winning newspaper, The Guardsman, editorialized against it, and about 50 people caravanned to Sacramento for a State Senate hearing. In their testimony they argued that core parts of the bill would ice out the working students and lifelong learners who make up the overwhelming majority of the City College student body, and slice the safety net for the most vulnerable. These provisions included giving enrollment priority to full-time students who could complete quickly; eliminating fee waivers for students whose grades fall below a C for two semesters; and sending students with more than 100 units to the back of the registration line.

Accreditation as a Weapon

City College was due for its regular accreditation review in 2012. The 17-member team ACCJC picked for the job included Commission President Barbara Beno’s husband and 10 people who either participated in the Student Success Task Force or came from schools that endorsed it. In the heat of the debate over the act, the commission came down with its sanctions.

“We were put in the crosshairs because of our stance on the Student Success Task Force,” says Wendy Kaufmyn, an engineering professor and activist with Save City College, a coalition of students, faculty, staff and community.

The Commission’s sanctions set off years of upheaval and chaos at the school. The six top administrators who churned through over the next four years made a series of decisions that drastically downsized the school—all justified, explicitly or implicitly, by the need to meet ACCJC mandates. From July 2013 to December 2015, these decisions were made by a Special Trustee With Extraordinary Powers (STWEP), an emergency manager who operated with neither transparency nor accountability. Neither students, nor faculty, nor the elected Board of Trustees had any say. Some of the policies put in by the takeover administrators pushed students out in obvious ways, notably the requirement for advance payments of student fees, and the closure of Civic Center campus.

The requirement for up-front payment took effect in January 2013. Students who couldn’t pay their full fee at registration, even before they received their financial aid, were referred to the predatory student loan company Nelnet(5) and “robo-dropped” from their classes by the school’s computer. This policy pushed out more than 9,000 students over four semesters. “At $4,676 per student in lost state reimbursements, the school lost around $40 million,” says Gonzalez. (After two years of student-led protests, the harsh payment policy was temporarily suspended in January 2016.)

The administration closed the Civic Center campus on a half day’s notice, just before the 2015 spring semester classes were due to start. They claimed a “seismic emergency” existed at the 750 Eddy St. building, though the structure had been flagged for retrofit in the 1970s. Classes for new immigrant English-language learners were cancelled with only a note on the door, in English; some 2,000 students were displaced. A strong community mobilization forced the college to find replacement space, but around 1,700 students lost their semester.

Other policies undermined the supports that help students stay in school. Student resource centers have seen their budgets cut by 25 – 50 percent, says Edian Blair Schofield, who works at the Women’s Resource Center and at Tulay, which serves Filipino students. The college’s array of resource centers and special programs serve Latino/a students, Black students, veterans, LGBTQ students, undocumented, disabled, homeless and formerly incarcerated students, among others.(6)

New “productivity” standards demand larger classes and defy teachers’ experience of what works. “I lose at-risk students in a class of 40 who I could keep in a class of 25 to 30,” says Edgar Torres.

And narrowing the course offerings deprives students of the very things that might draw them in, according to Joe Drake, a formerly incarcerated student who is preparing to transfer from City College to a four-year school. “They want to cut music, Poetry for the People, a lot of the ethnic studies classes—the classes that help a person find out who you are, that help people be interested in staying in school,” says Drake. Diversity studies—ethnic studies classes, women’s and gender studies, labor and LGBTQ studies—have been particular targets since the crisis began. Tarik Farrar recalls Interim Chancellor Pamila Fisher telling him on more than one occasion in 2012, “Your diversity departments are in our sights.”

Students Gone Missing

“We’ve lost a generation of SFUSD graduates,” says Leslie Simon, who teaches Women’s Studies at the college and founded Project SURVIVE, the school’s sexual violence prevention program.

The 10 percent decline in new SFUSD graduates entering City College in 2014 mirrored the percentage of students who didn’t go to college at all.(7) Without CCSF, their options are limited, according to Shanell Williams, who was the student representative on the Board of Trustees when the crisis hit. “What do they want low-income students to do? Either be stuck in a low-wage job, the underground street economy where they may end up in jail or prison—or go to a for-profit trade school, where they will be saddled down with debt and have little to show for it,” Williams says.

The most vulnerable and least mobile students have been hit hardest by what activists call “the racist push-out policies”; a majority of the displaced students are students of color.

“Consistently since I started in 2012 the population of African American students has gone down, and many of the students who are there are struggling with housing issues, which makes staying in school hard, or with economic issues that affect their staying in school,” says African American Studies Professor Aliyah Dunn-Salahuddin. She grew up in the Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood in San Francisco, and has seen her whole family pushed out of the city.

“City College is San Francisco’s most important working class institution,” says American Federation of Teachers (AFT Local 2121) Political Director Alisa Messer, a San Francisco native. “This [the downsizing of the school] is a case study for who’s leaving San Francisco, who’s being pushed out, another way we’re making San Francisco inhospitable for working class students and students of color,” says Messer, who teaches English at CCSF.

Students, Faculty and Community Push Back

Hundreds of people turned out for a community meeting in July 2012, shortly after the sanctions hit. Many channeled their energy into the campaign for the parcel tax to support City College; the tax, Proposition A, passed in November with 73 percent of the vote. San Franciscans also turned out en masse at numerous marches, rallies, and trustees’ meetings. Students, most militant of all, occupied the administration building and the mayor’s office.

AFT 2121, and the California Federation of Teachers, played a key role in the Prop A campaign, in securing state funds to stabilize City College during the crisis, and in legal and regulatory challenges to the ACCJC. By March 2016 the commission was facing loss of its federal license, and the California Community College Board of Governors voted to reform and replace the commission. Although the ACCJC is still scheduled to render its final decision on accreditation in January 2017, with no appeals allowed, City College supporters are cautiously optimistic.

“We’re moving forward,” Messer says, “but there are no guarantees. We must stay vigilant and remain organized.”

Now activists must win support for rebuilding CCSF as an open access institution for 100,000 students, rather than as a half-size workforce training school. The shock treatment handed down by the Accrediting Commission and the state takeover replaced almost all the senior administrators at the school with people committed to an austerity agenda. Like most austerity regimes, this one includes an all-out attack on unionized workers. (See “Faculty Fight For Fairness”) Turning the college around will require, in part, an aggressive Board of Trustees and supportive city government.

For-profi t schools stand to gain from the downsizing of City College. Here, an ad on a kiosk for the CCSF newspaper. The other side of the kiosk displays a recruitment poster for the US Army.

Photo: © 2016 Marcy Rein

“Gentrification and education reform are part of a coherent vision of a future world,” says Tarik Farrar, and that vision is being contested on many fronts in San Francisco.

Major elected offices will be in play this year. Seats on the Democratic County Central Committee will be up for grabs, and in this bluest of cities, these endorsements can make or break campaigns. Four spots on the City College Board of Trustees will come open, though incumbents are expected to run for three of those. The three progressive stalwarts on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors—John Avalos, David Campos and Eric Mar—will be termed out, and much rides on the races to continue their politics on the board.

Proposition K, passed by San Francisco voters in November 2015, commits the city to using surplus land for affordable housing; Proposition C on the June 2016 ballot would more than double the amount of affordable housing required in large, market-rate developments. Developments at CCSF’s 33 Gough St. site and the Balboa Reservoir will be moving through the public process as anti-displacement activists battle the huge “Beast on Bryant” development at 18th and Bryant Streets, and remain on alert in the fight over luxury housing development at 16th and Mission.(8)

City College student activists are also making links to the organizing against police brutality they see escalating with the gentrification in the city.

“Anti-gentrification, anti-police brutality, the fight for City College—all these struggles are connected, tightly tied together,” says Win-Mon Kyi, a core student organizer with Save City College.

The new proposal to make City College free to San Francisco residents and workers could address both the school’s enrollment drop and the city’s deep inequities. Supervisor Jane Kim introduced the “Free City” proposal April 19, with the strong backing of AFT2121 and several community groups. The cost of the plan could be offset by a luxury real estate transfer tax, which would go before voters in November 2016.

“Free City has everything to do with who’s being pushed out, and gives San Francisco an opportunity to reclaim the promise of public higher education,” Messer says. “To make this part of our next steps in the struggle—it’s like a phoenix rising from the ashes.”

The Research Committee Serving the Movement to Save City College contributed reporting to this story.

Notes

1. California Community College Chancellor’s Office Datamart, accessed March 23, 2016.

2. Chicago Teachers Union, “The Black & White of Education in Chicago’s Public Schools: Class, Charters & Chaos,” (pdf) Chicago Teachers’ Union, 2012

3. Pauline Lipman, High Stakes Education: Inequality, Globalization and Urban School Reform, RoutledgeFalmer, 2004, pp. 7 – 8.

4. Ibid.

5. NelNet overbilled the US Government by at least $278 million between 2003 and 2006. See Alan Michael Collinge, The Student Loan Scam, Beacon Press, 2009, p. 70.

6. These supportive programs include Disabled Students Programs and Services, EOPS, Transitional Studies, the multi-cultural retention programs and the Resource Centers (Family, Women’s, Queer, Multicultural, Veterans, SCube, VIDA, the Bookloan Program, HARTS, Guardian Scholars, Project SURVIVE, the Gender Diversity Project, Second Chance, WAYPASS, the Writing Success Project, Peer Case Management.

7. SFUSD Graduates.

Postsecondary Attendance Rates. (pdf)

8. For more on the 16th and Mission development fight, see “Who Gets To Live Near Transit,” by Dyan Ruiz and Joseph Smooke, RP&E Vol. 20-1, 2015.