After Internment: Oakland 1945

Historical Essay

by Karen Tei Yamashita

Personal effects arriving at the Oakland West 10th Methodist Hostel are being checked by Saburo Sasaki, Gila River (left); Mr. Joseph S. Aoki, Topaz; and Mr. John Yamashita, Topaz. The latter is director of the hostel.

Photographer: Mace, Charles E.—Oakland, California. 6/18/45, courtesy Bancroft Library

Toward the end of February 1945, John Yamashita stepped off a train at the Oakland depot, returning home after three years’ absence. Meanwhile Alma Gloeckler had been teaching in the Oakland public schools and had spent the previous summer at Tule Lake Segregation Center. She was at Tule Lake in Christmas 1944, when the closing of camps was announced. As John’s train approached, Alma, a lone stranger, showed up to meet him at the depot. She wrote:

’’I can still see John, standing at the Oakland train depot with a small luggage, as I got out of my little black depression Chevy. He was serious. We greeted one another formally and introduced ourselves . . . I told him that Josephine Duveneck of the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) had informed me of his arrival. John was just a little less serious, and seemed reassured. “Why are you doing this?” he asked right away. That remained a short question and a long time to answering.

Alma accompanied John to the West Tenth Japanese Methodist Church to begin the work of reopening its doors as a hostel to receive returning Japanese Americans and to distribute the stored belongings—furniture, mattresses, stoves, refrigerators, sewing machines—left behind by some 135 families. Alma gave John that black depression Chevy to pick up returnees and supplies, and daily she and a cohort of what she called settled people came to scrub, clean, and paint the church’s Meader Hall. Old cots used in camp were redeployed, blankets gathered, and Alma’s friend Bernice Cofer organized Lakeshore Avenue Baptist Church members to stand in ration lines at Capwell’s to buy sheets and pillowcases, two to a customer. Margaret Utsumi and John’s old Berkeley schoolmate Ish Isokawa returned as those eventually settled people—Margaret to set up the kitchen and dining service and Ish to work long hours at John’s side, shipping trunks and crated boxes of belongings to those who’d never return. Many years later, John would write to Ish: You know I’ve never really thanked you for that year back in ’45 when you ran the Hostel and emptied out West Tenth Gym . . . John got a small stipend from the Methodist Youth Fellowship, but Ish and Margaret worked those years without pay. In the next year and a half, three thousand people would pass through the church into relocated and recuperated lives. In this busy churning of folks there was little time to thank anyone, but perhaps also little will to show gratitude. Mean years had turned people mean; that is also to say terse, speechless, socially closed and, as you can imagine, afraid and mistrusting.

Alma’s memories emphasized John’s careful protection of the hostel’s feeling climate, protective of the feelings of the returnees as much as of those who offered succor to them. John wanted something back, an emotional generosity that fulfilled his beliefs. He cultivated, Alma described, a heightened awareness that met every person and every contingency. While Alma understood that hostilities had to be thawed out, she was impatient with public ignorance and continuing negative attitudes toward the returning Japanese and said so. She remembered John’s reaction: John listened thoughtfully, head down, and then said softly . . . “Don’t make any enemies for yourself, on account of us.”

Perhaps John was already aware of the disturbed feelings of Lee Mullis who had, with his father Fred, watched over and protected Meader Hall and its contents during the war years. This must have meant constant vigilance against certain vandalism, checking it at night, repairing and boarding up broken windows. It must have also meant incurring the wrath and abuse of neighbors, losing friends, becoming over time isolated and worn with responsibility. Lee Mullis, the only Caucasian member of a Japanese church, had said good-bye to friends and their fellowship, and for that, had taken on an almost impossible promise, the burden of obligation. Miraculously, he kept his promise while so many encumbered others had not, abandoning or selling what was not theirs. When the war ended and relief seemed in sight, Lee opened the church and hoped to welcome home his friends. Who he welcomed home were an unsettled and broken people, refugees in their own country, returned to lives forever changed, psychically contained by a thin veneer of politeness that for many years would hide deep fear, suspicion, and pained resentment. If no one thanked Ish for the next thirty years, indeed, no one thought of thanking Lee and his father. Old friends never returned, never sent word, or sent for their stuff with a few lines in a telegram. Other friends returned, stayed provisionally at the hostel, and silently left.

In John’s Pastor’s Record of Funerals, the first recorded funeral at Oakland West Tenth was that of Fred Thomas Mullis on January 12, 1946. The Oakland Tribune’s obituary section read

Death: Mullis—in Clear Lake woodlands, January 7, 1946. Fred Thomas Mullis, husband of the late Fannie K. Mullis, father of Loren Lee Mullis, Mrs. B. W. Payne, and the late Mrs. E. H. Hawkins. A native of Kansas, aged 70 years, 2 months, 21 days. Friends are invited to attend the services at the Japanese M. E. Church. 10th and West Street, Oakland, Saturday, January 12, 1946 at 2 o’clock p.m.

John presided over the funeral and burial, but who among the original congregation at West Tenth joined Lee Mullis in mourning his father? A sad absence surrounds this event, the details of which have been entirely lost. Some time after his father’s death, Lee also left Oakland without word, headed to New York, never to be thanked and never to be heard from again.

In another two years, Alma, too, would leave for New York to pursue a graduate degree in education at Columbia. I’m not sure that Alma and John ever met again. It was many years later that I finally met Alma Gloeckler. At the age of one hundred, she remarked with amused disdain that age is not a disease, although dementia is, and Alma to the very end had almost every marble in place. Her hair coiled up in an elegant French braid, Alma looked at me with bright curious eyes, and I knew she searched for and saw her old friend John, that he somehow appeared between us and lived in our moments together, her remembering and storytelling. John saved three letters from Alma that he himself dated around 1946; reading them, after reading all his seminary papers written during the war, finally I sensed what had been absent in his seminary work: a kindred spiritual and intellectual partnership. The letters wander, but with thoughtfulness and spiritual inquisition, a sense of pleasure in thinking a thought through without recrimination, but with expectation and surprise. Though John’s corresponding letters are lost, this insight remains. For John, 1945 to 1947 were years of intense physical and emotional work, the practical labor of rebuilding a postwar community, but it was also a period of intense personal, political, and philosophical questioning. Alma’s correspondence makes it clear that the labor of the period—practical and philosophical—would be the underpinning of John and Alma’s understanding about civil society and civil rights.

The questions implied in the letters are philosophically enormous and uncontainable. They boggle and pain the mind. Why and how should one choose a spiritual path? What is the church? How does one cultivate a conscience? How do we know we know? Is belief logical? What is prayer? What is confession? What about the simplicity of a life lived daily without question? What is suffering? Sacrifice? Giving? What is education? Creativity? What are the laws of nature, and what is human freedom? What is the meaning and danger of giving and receiving? What is love? Alma and John together began with the assumption of a spiritual center and caring social conduct, Alma influenced by her Canadian Mennonite family and cultivated through Quaker membership, and John, being the son of Japanese immigrants and a student of Rollo May, Reinhold Niebuhr, and Howard Thurman.

Among these heady inquiries, I am drawn to Alma’s conscientious struggle with her fluctuating position as giver and receiver, her understanding of the uneven power and privilege of the giver. She wrote

’’It seems that if we are going to deal affectively with one another, helpfully and with understanding and strength—we need to know something more about just what that relationship between giver and receiver can be at best. Love itself is a wonderful enlightener because it adds patience and kindliness—hope and faith to a relationship, but it too needs all the enlightenment it can get in a complicated conflicting social order. So back I am at the question of self—to lose it and yet to find it—more viably. I do think that we must realize that at best it involves repeated failures even in the realm of giving—suffering and a feeling of futility at times . . .

John asked Alma: Why are you doing this? It was not, as Alma knew, a simple question. Perhaps it was a forewarning. Homer would say that the nature of true charity is much like taxes, an understanding that this is how a civil society is paid for. Charity must be its own reward. But what about love? Perhaps Lee Mullis held forth with the expectation of love and family, but he got stuck at home with all the old stuff that, finally preserved and saved, did not really matter. How could he know? It’s difficult to think clearly ahead about why you might do anything—why take on love, why risk heartbreak? The only other thing I’ve been able to learn about Lee Mullis is that he died at the age of eighty-two in Glen Cove, Nassau, on Long Island, in 1987. Forty years lived after the war, although the resilience of bitterness is unpredictable; hopefully, as John and Alma would have wished, love intervened. . .

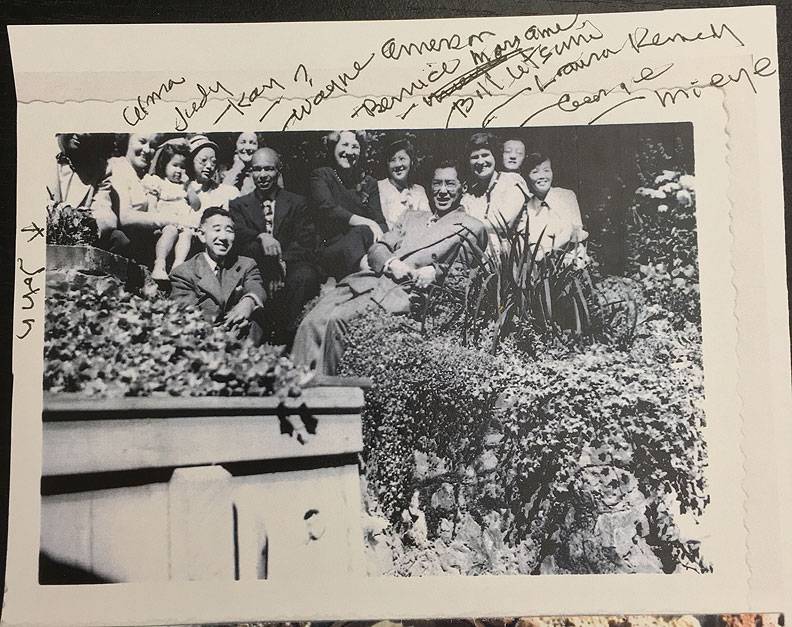

When I met Alma Gloeckler, as I said, who was around the age of one hundred years, she had a particular gift she wanted me to have. It was a black-and-white photograph of a group of people taken on a hillside garden somewhere in Oakland. The photographer had almost chopped the heads from the frame, privileging the foreground’s ivy draping over volcanic rock, but somehow, what Alma called ‘’our group’’ is all there. Their inscribed names have begun to fade from the back of the photo, the script confounding exact spelling:

- Gerry Cambridge

- Alma Gloeckler with Baby Judy Utsumi

- Kay Yamashita

- behind is Petrofae Cambridge

- Daisy Froderburg Funderley

- Rev John Yamashita

- Wayne Amerson

- Bernice Cofer

- Mary Ann Utsumi

- Bill Utsumi

- Laura Kennedy Robbin

- E. J. Kashiwase

- Miye Kashiwase

Alma repeated that this was our group. Every weekend we would meet and discuss things and make a plan. And then we would go, for example, to a restaurant that hadn’t been behaving very nicely, and we would all sit down and order our meal.

I nodded without understanding, but Alma was patient and insistent. Oh, those were difficult times. You have no idea. People didn’t want to see the Japanese back. They were very mean and hostile. We had to do something.

So you all went as a group.

Yes, we were all mixed up, so they had to serve us.

You did a sit-in?

Yes! she exclaimed with enthusiasm. We did direct action!’’

She pressed the photograph into my hands along with a VHS documentary tape about the life of Bayard Rustin. Bayard, she nodded, he was one of us. In 1942, Rustin traveled for the Fellowship of Reconciliation to civilian public-service camps as well as to assembly centers and concentration camps to support the internees and to rally folks out of bitterness toward activism. In a short report dated October 15, 1942, to John Swomley, Rustin wrote: When I arrived at Manzanar the F.O.R. group had already arranged a car and I set out immediately and toured for six hours . . . This was a great experience and I shall turn in a complete report of several pages on conditions in the camp . . . By the end of the war, Rustin himself would be imprisoned as a conscientious objector who refused any civil participation or pacifist support of the war.

I date the photo to around 1947, when Kay would have had a summer visit to Oakland. In April of the same year, Bayard Rustin set out with fifteen fellow travelers on his Journey of Reconciliation, an interstate bus ride through the states of Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky to test the abolishment of Jim Crow, and sixteen years later, Martin Luther King, Jr. would write from a Birmingham jail.

My folks came home to a divided community of those who had said yes-yes and those who had said no-no and everyone in between. There was an unspoken partition and bitter heartache, still felt to this day, but everyone was in the same boat generally—hated, feared, shamed, still considered the enemy that had been conquered, whose people had killed our Americans. John did not bemoan those years of exile but encountered a larger world and meaning that might never again place him particularly in any one place or home. After so much wandering, I am directed to this unanchored but planetary place of his heart. And Alma wanted me to know something about what it takes to live a hundred years: survival, as you will say, is about the connections between us. For a brief and forgotten moment in 1947, reconciliation met in the contrapuntal. The names are inscribed but the people forgotten, the photograph fading evidence, and the story but a ripple in time.

Used by permission from Letters to Memory (Coffee House Press, 2017). Copyright © 2017 by Karen Tei Yamashita.