Ewing Field

Historical Essay

by Angus MacFarlane

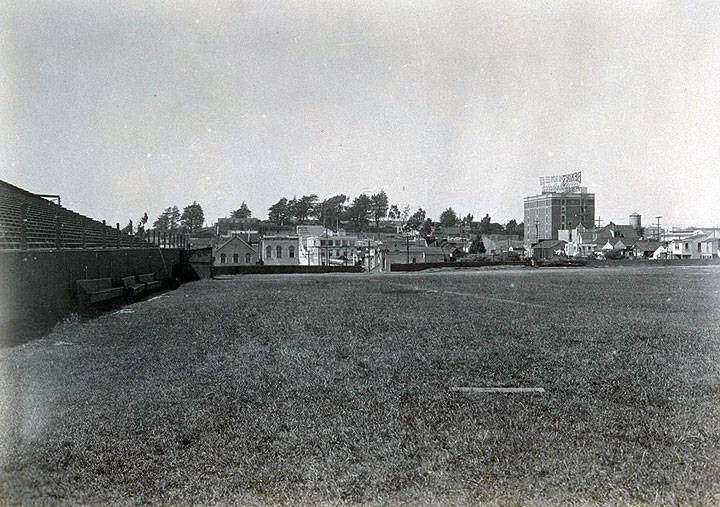

North from the center of Ewing Field, the Bekins building on Geary near Masonic visible in distance.

Photo: Online Archive of California

On May 16, 1914, two years after the magnificent luxury liner HMS Titanic collided with an iceberg in a too-tragic, too-ironic to be true event, a metaphorical Titanic encountered a metaphorical iceberg in San Francisco.

Grandiose beyond description, the unsinkable Titanic’s fate still intrigues and haunts us more than a century after it sank, engendering sympathetic headshakes and “poor Titanic” comments.

Also grandiose beyond description, San Francisco’s metaphorical Titanic (on the rare occasions that it is ever recalled) invariably elicits snorts of ridicule and dismissive pronouncements such as “he should have known better” or “what was he thinking when he built it there?”

“It”—our metaphorical Titanic—was Ewing Field, a magnificent baseball stadium that was to be the home of the Seals for the next twenty years. “He” was J. Cal Ewing, Seals owner responsible for the field that bears his name. “There” was Lone Mountain.

Even though the Titanic survivors have all passed away, the passengers and crew of the ill-fated ship are an indelible part of history thanks to books, movies, documentaries and new discoveries that keep the old story alive.

Likewise there are no survivors per se from Ewing Field’s collision with the metaphorical iceberg—San Francisco’s summer fog—because there were no casualties. Yet for the persistent tales and exaggerations of that summer-long, slow motion metaphorical collision a century ago, Ewing Field’s death toll should have at least equaled the Titanic’s.

Cal Ewing lived for baseball and for half a century he was willing to spend his money, get his hands dirty, and his knuckles bloody to advance the game. Unfortunately his association with the field that bore his name remains his sole legacy to San Francisco baseball: part clueless laughing stock, part tragically misguided character.

One hundred years later the story of Ewing Field is still grossly misunderstood, heavily mythologized, factually inaccurate and historically incomplete. Sadly, even histories of San Francisco baseball totally overlook Ewing Field’s complex origins, Cal Ewing’s selfless motivation and struggles on behalf of Seals fans, and the decades of use the facility provided San Francisco sports enthusiasts after the Seals left.

It is time to revisit Ewing Field to set the historical record straight.

(NOTE ON METHODOLOGY: all references are from contemporary issues of San Francisco and Oakland newspapers unless otherwise noted.)

1906-1907

WITH TIME RUNNING OUT, CAL EWING THROWS A HAIL MARY

The road to Ewing Field began on March 5, 1906, when Cal Ewing ended two decades as an Oakland sports fixture with his purchase of the San Francisco Seals. The $42,500 transaction whereby Ewing, his uncle Frank Ish, and John Gleason took over the Seals happened so quickly that Ewing, the majority owner of the Oakland franchise of the Pacific Coast League, did not have time to sell his Oakland shares. The Oakland Baseball Association (the corporate name for the Oakland team known as the “Commuters”) met on March 15 to decide how to buy out Ewing’s stock, but no action was taken other than to elect Secretary Ed Walter to fill Ewing’s vacated presidency of the association. Ewing surrendered his Oakland stock to be held in trust by President Walter until it could be sold.

The first issue of the San Francisco Seals weekly magazine/scorecard proclaimed, “The season of 1906 of the Pacific Coast League opens up under the most auspicious circumstances and the omen points to a successful season both for clubs and managers.”

Play began on April 7 with Ewing’s Seals defeating the Seattle Siwashes 4-0 before 6,000 fans at Recreation Park at 8th and Harrison. One week into the season no one had expressed any interest in buying Ewing’s shares of the Oakland club, giving him reluctant ownership of 1/3 of the 6-team Pacific Coast League. This potentially exposed him to charges of “syndicalism”, or the unethical practice of having interests in more than one club in a league. However, the league completely understood Ewing’s unique situation and knew that he had no intentions to corrupt the game.

On April 17, 1906, the Seals were tied with the Los Angeles Angels for first place. The Seals were scheduled to play Portland at Recreation Park the next day, but that contest was indefinitely postponed by the events of April 18, 1906. It also rendered Ewing’s holdings in the Oakland club worthless.

Along with everything south of Market, Recreation Park was lost. All that did not burn was part of the grandstand and the flag that had been saved by groundskeeper Bill Johnson, who climbed the pole and “saved the emblem so that when the Seals come back to play, the same old flag will fly in center field”.

Oakland’s field at Idora Park in North Oakland was undamaged, but the team was stranded for the time being in Fresno. The other PCL cities—Los Angeles, Fresno, Portland and Seattle—were physically unaffected by the disaster. Financially it was a very different story. The league depended on San Francisco for its survival. The population of San Francisco and Oakland was greater than the four other cities combined, and Recreation Park was the chief moneymaker for the league. Visiting clubs took a 30% share of the gate money and they were always assured of making a profit when they came to the Bay Area.

Furthermore, since 1899 San Francisco and Oakland had a unique arrangement whereby Oakland played the majority of its “home” games in San Francisco. When the Oakland team was “at home”, the morning game of Sunday double headers and one weekday game were contested in Oakland. The afternoon game of the Sunday double header was played at Recreation Park, along with all but one of Oakland’s weekday games.

Conversely, when Oakland was on the road, the Seals would “host” the visiting teams in the East Bay on Sunday morning as well as a second game during the week. The other games were at San Francisco’s Recreation Park. This practice continued into the 1920s.

With Recreation Park gone, the league was in dire straits. At the time of the quake the Seattle team was in Los Angeles and the two clubs continued to play out their scheduled games. Portland, scheduled to play in Los Angeles after their San Francisco series, managed to make their way south with just the clothes on their backs.

The third week of the season had Oakland playing San Francisco, but clearly that was not going to happen. On April 27 PCL President Eugene Bert ordered Seattle and Portland back to their home cities where they would host the temporarily homeless Seals and Commuters while Fresno and Los Angeles would alternate series until some semblance of order could be established.

During this time Ewing, calling on his twenty years of sports management skills and knowledge, emerged as the league’s savior. He promised to meet his financial obligations to his San Francisco and Oakland teams and he guaranteed the payroll of the Fresno club. Estimates of Ewing’s contribution to saving the PCL range up to $100,000.

Despite winning the 1905 PCL pennant, Los Angeles’ owner Jim Morley claimed to have lost money that year. In addition he lost $78,000 of income property in the San Francisco disaster and was on the brink of disbanding the Angels when Ewing intervened and convinced Henry Berry to buy the club.

Baseball returned to the Bay Area on May 24 at Oakland’s Idora Park, which would be the Seals’ home for the remainder of the 1906 season. San Francisco, called “Cal Ewing’s Refugees”, defeated Fresno before “a good crowd—not of the Recreation Park variety, but far larger than Idora Park is used to” which included, President Bert, and Ewing.

The Examiner was the first newspaper to call for baseball’s return to San Francisco. On June 1, it appealed Mr. Ewing Bring the Seal Herd Home, noting, “Yesterday more than three thousand crossed the bay and paid the price at Idora Park to see the Seals perform a little baseball matinee.” It ended with “the fans here want their baseball club back.”

Ewing responded that he fully intended to return to San Francisco as soon as possible, but that the 8th and Harrison site was not an option. He hoped to find a new location 15 or 20 minutes from downtown, secure a long-term lease, and give San Francisco the best ballpark in the country. (At this point in baseball’s evolution, teams rarely owned the land on which their ballparks stood. The first team-owned field in San Francisco would be Seals Stadium which opened in 1931.) Three real estate agents working full time for Ewing scoured the city for suitable sites but they were all ruled out because of small size, huge cost or both, prompting President Bert to complain, “A vacant lot is not worth half the price most landlords are asking.”

Three months following the earthquake the Examiner had the unenviable chore of reporting

NO GAMES HERE THIS SEASON

Price of Material Makes It Impossible for League Officials to Build Grand Stand.

Not only were high land prices frustrating Ewing, but as the pace of rebuilding the city accelerated, the demand for lumber was pricing San Francisco out of the ballpark market for 1906.

September arrived and no progress had been made. Compounding the crisis was the news that Idora Park was going to be cut up into building lots at the end of the season, leaving both Bay Area clubs homeless.

“Where are they going to play?” the Examiner wailed. Two long-shot possibilities were mentioned: building combined facilities for both clubs in either Emeryville or Alameda. The Examiner reminded its readers that in the 1880s teams from both Oakland and San Francisco played at the island community and the games were well attended by fans from both cities. The article concluded on this pessimistic note: “There does not appear to be overly much merit in either scheme, but both are better than nothing at all. There will be no playing grounds in San Francisco in 1907 if the property owners keep up the high prices.”

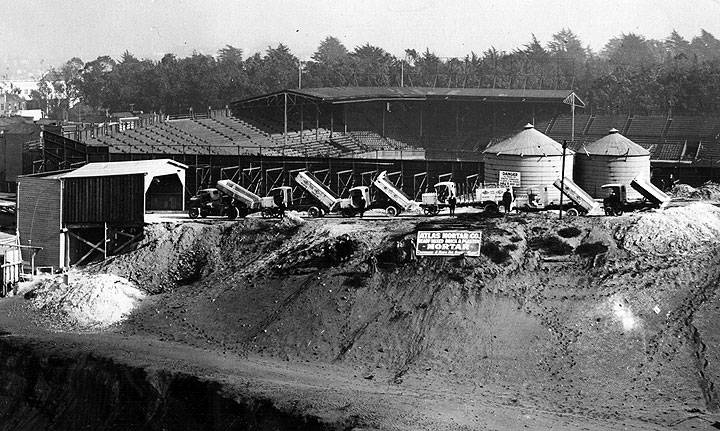

Ewing Field behind sand hill being quarried near Masonic and Geary, 1914.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

Ewing was a patient man with high standards who emphatically reiterated that although he sympathized with the fans’ frustration, he was unwilling to build something out of expediency that he and San Francisco would soon regret. He wanted a facility that San Francisco would be proud of. He already had three stadiums to his credit, so he was intimately familiar with the complexities involved in land acquisition, financing, construction and public access. In 1897 he was part of the group of sports promoters who created Recreation Park at 8th and Harrison. In 1899, as owner of the Oakland baseball team, he was responsible for securing a new stadium for his club. In 1902 he saw to the creation of Idora Park, where the Seals were temporarily located.

When the baseball season ended on November 3 there was no hint of where either team would play in 1907. Nor had there been any significant news on the stadium front since September. The Call, however, shared its observations and opinions on what the new park should be like: “The first thing is to get a real baseball grounds in the city. It should be fitted up with a swell grandstand, not a rattletrap affair like the one that graced Recreation Park for so many years.”

On November 10 Jack Gleason, Seals minority owner, broke the long silence to report that several offers had been received, but no details were given. That was the state of affairs until the PCL’s annual meeting in Los Angeles on December 8. Eugene Bert was reelected league president, opening day for the 1907 season was set for March 30, and word from the meeting was that the Seals would host Portland on that date in a new stadium on their former grounds at 8th and Harrison.

However, the year ended with the same depressing news that the local magnates still hadn’t found a home for the Seals. The optimism President Bert expressed three weeks earlier that the Seals would return to 8th and Harrison had now dissipated.

But there was a glimmer of hope: a new potential location was mentioned for the first time, near the old Woodward’s Pavilion on 14th and Valencia.

Two more weeks passed with no news. Then, on January 13, 76 days from opening day, Jack Gleason announced “San Francisco will have a ball park this season”. It even had a name: Recreation Park. But Gleason wouldn’t reveal its location. The public and the press had to accept Gleason’s vague pronouncements that “the deal will be closed as soon as some minor details are settled and the papers are signed sometime this week”. As soon as that was done the location would be revealed.

Gleason further assured the public that once work began there would be no delay because the Seals had arranged to dedicate the new stadium on March 24 (six days before the league’s opening day) with a game against the New York Giants—70 days hence.

On January 16, (minus 67 days) the Examiner scooped the other papers to report that the mystery site was the old 8th and Harrison corner. The Seals were all set to finalize the deal when the property owners abruptly doubled the rent, thus ending negotiations. The Examiner then double-scooped the other papers by revealing that the Seals had a Plan B: 14th and Valencia.

A week later (60 days to go), readers of the January 23 editions of the Chronicle and Call were understandably confused. According to an impatient Chronicle headline, it was

TIME FOR BALL PEOPLE TO MOVE—Too Much Apathy Displayed by the San Francisco Management.

San Francisco seems no nearer the solution of the perplexing problem of a baseball park than it did a week ago, and at that time the promoters declared that they had practically made all necessary arrangements.... For a week past it has been the same old story. The managers will tell you that “the deal is to be closed tomorrow.” If baseball is to prosper, there must be a park on this side of the bay.

The Call, on the other hand, wrote

WORK COMMENCED ON UP-TO-DATE BALLPARK.

The work of clearing the grounds at Valencia between 14th and 15th Streets has commenced and the grounds will be ready for opening day.

Four days later the Chronicle lamented, “Another week has passed and still San Francisco has no ball park, nor does any one seem to know when they will have one. Ewing is unable to tell when the lease will be signed, let alone work commenced.” Standing in the way of the new ballpark were several tenants who were demanding more money for their leases.

With the Giants due in 56 days “a well known contractor” pontificated that it would be impossible to have the grounds ready in less than three months. The same day Eugene Bert resigned as President of the PCL.

On January 28, (minus 55 days) San Francisco baseball fans could finally exhale—the deal for a ballpark site had been successfully negotiated. The site, of course, was on Valencia Street between 14th and 15th. It was described as being larger than the old Recreation Park. At first the dimensions were listed as 550 feet by 350 feet, but a week later it shrank to 435 feet by 325. The grandstand would seat 4,000 and the bleachers another 8,000. A five-year lease was signed, but Ewing hoped to extend it to ten years. It had cost the Seals $20,250 for the lease buy-outs and another $40,000 was anticipated for construction costs.

The new home of the Seals had an interesting history stretching back more than half a century. In 1854, when the city’s western boundary was Larkin Street, the San Francisco Chemical Works were built on a 540-foot by 560-foot plot of land 200 yards from the Mission Plank Road that ran to Mission Dolores. On official maps the chemical works was bounded by Valencia, Guerrero, Sparks and Tracy Streets, but in the sparsely populated region one mile southwest of Yerba Buena Cemetery, those “streets” were vague abstractions in the area generically termed “Mission Dolores”.

Founded in 1853 as Meyer, Landis and Company, the chemical works’ initial purpose was to supply the United States mint with nitric acid used in the processing of raw metals into gold and silver coins. Production of nitric acid required vast quantities of sulphuric acid, a volatile substance that was not easily or cheaply transported. By necessity this was manufactured on-site.

In 1854 the business fell into the hands of Egbert Judson, John Shepard, H. R. Coon and M. Farmer. Through death and buy-out, Judson and Shepard became sole owners in 1860.

In 1866 Woodward’s Gardens, the city’s first zoo and amusement park, opened across Valencia street from the chemical works. Around this time Tracy and Sparks Streets had been renamed 14th and 15th Street respectively.

In the early years the facility’s remote location was ideal for its purpose, but as the city expanded, it grew toward and then around the once-distant works. This brought increased complaints of noxious fumes and odors that not only killed flowers and delicate shrubbery, but also sickened and killed people in the district. Physicians refused to treat patients who lived near the works. By 1877 the constant complaints and petitions to City Hall resulted in the San Francisco Chemical Works being declared a public nuisance in a thickly settled neighborhood. In 1878 it moved to Berkeley and the block was cleared of the abandoned structures.

Co-owner Egbert Judson continued to live across the street from the plant in the house that had been his home from 1861 until his death in 1893. He never married and had no family. His estate, which included his interest in the chemical works and property (including the former site of the chemical works) was administered by the Judson Estate Company.

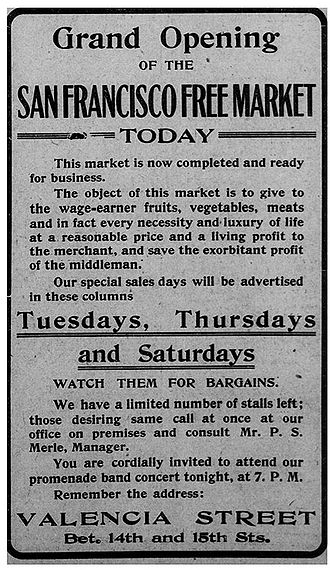

Over the ensuing years the entire frontages along 14th and 15th Streets were sold and developed, as well as 195 feet along the frontage of Valencia Street and 358 feet of Guerrero Street’s frontage. The undeveloped central portion of the block became a dumping ground and later a vegetable garden. (See Figure 1.) Four days before the earthquake the Chronicle reported “About 4½ acres on the west side of Valencia Street between 14th and 15th, having frontages on Valencia, Guerrero and 15th Streets have been leased by the Judson [Estate] Company for five years at a total rental of $18,000.” The lessee was the San Francisco Free Market (the turn of the century term for farmers’ market), which planned to erect three 40’ x 200’ buildings that would have 500 stalls for farmers, growers and producers to sell their good directly to the public. This was first large scale direct-to-consumer produce business in San Francisco. Naturally the earthquake delayed their plans, but by August the Free Market was prepared to open.

This was to be the future home of the Seals.

Figure 1: Development on the block Valencia/Guerrero/14th/15th prior to the 1906 earthquake and fire.

Sanborn maps

Now that the Seals had secured the property, a tremendous amount of preliminary work had to be done in a brief period of time before the erection of the grandstands could begin. The Free Market’s structures had to be cleared off the site before the grounds could be graded and brought to street level. These were the days before heavy machinery, so all the work was done by men and animals.

Nonetheless, Ewing publically expressed his faith that the field would be ready for the exhibition games against the Giants, now scheduled for March 16-18—a mere 47 days away. His confidence was undoubtedly based on his experience with the first Recreation Park, which was constructed in just over a month in 1897. Construction methods were still simple, involving wood, nails, picks, shovels and lots of sweaty men.

The contract was given to W. F. Hanrahan, who had a reputation as a real hustler when it came to getting the job done. He also faced a $500 per day fine for being late. Hanrahan had men on the grounds as of January 27 and vowed no let up as long as the weather permitted.

On February 17 (minus 27 days) the Seals conceded that there was not enough time to plant grass, so the entire field would be dirt for the first season. But, Ewing maintained, there was still enough time to complete construction.

On February 19 Hanrahan said “I will have 100 mechanics on this job this week and perhaps, more.” Twenty teams were set to level an embankment in the outfield and spread it about. The foundations for the grandstands were already in place. He said that it will be “fully as large as [the first] Recreation Park.

Across the bay, the Commuters were completing work on their “new” home, Freeman’s Park. Ewing was well acquainted with it, having overseen its construction in 1899 as owner of the Oakland Club in the California League, the predecessor of the Pacific Coast League. It had been Oakland’s home field till 1904 when they moved to Idora Park. Now, Ed Walter, President of the Commuters, was moving the Commuters back to the new and improved field.

On February 24, (minus 20 days) as loam by the ton was being spread over the field under the watchful supervision of groundskeeper and Old Glory savior Bill Johnson, the Seals extended their Recreation Park lease to ten years, up to May 1, 1916.

At the PCL owners’ meeting over the weekend of March 1-3 Fresno and Seattle were dropped, leaving San Francisco, Oakland, Portland and Los Angeles in a 4-team league. Ewing, now owner of half the PCL teams, was elected league president. The season would still start as planned on March 30, but with a revised schedule.

Sparing no expense to have the work completed for the Giants’ arrival on March 16, carpenters worked all day Sunday, March 3, at double pay. By March 5, 300 men were at work on the grounds. Jack Gleason said that the field would be ready “by this week or next. The grounds won’t be in perfect shape, but good enough to play on.” Implied in all of his optimism was the hope that the weather, which had cooperated thus far, would still hold.

On March 10 it began to rain. By 3 o’clock it was raining hard enough to stop work. The games were a week away. On March 13 electric lights were installed to permit nighttime work. It was coming up to the bottom of the ninth inning and against all odds it appeared that the Seals would indeed have the new Recreation Park ready for the Giants.

But Mother Nature always bats last. A light drizzle began to fall on the afternoon of March 15, the day before the Giants’ arrival. The field was as ready as it would ever be, but the grandstands were still not entirely finished.

At sunset, Ewing left Recreation Park with electric lights ablaze and the field literally covered with bonfires which served the dual purpose of providing additional illumination as well as heat to dry out the damp field.

“There will be baseball” he declared, “unless there is a heavy storm before 3 o’clock tomorrow afternoon. Everything will be in readiness for the game.”

The Call wrote in its morning edition of game day, “A slight sprinkle of rain will not prevent the game and unless the field is transformed into a real, live lake, the game will be played.”

But the slight drizzle turned into a storm that flooded the field, leaving it a “fenced-in ocean of sticky mucilaginous mud.”

Regardless, some 200 curious fans braved the downfall and came to the park to see that the diamond was indeed a lake with a muddy island where the pitcher’s mound would have been. McGraw and a few Giants took a quick look at the aquatic scene and agreed it was not playable.

The rain that cancelled the Giants series continued for the next two weeks.

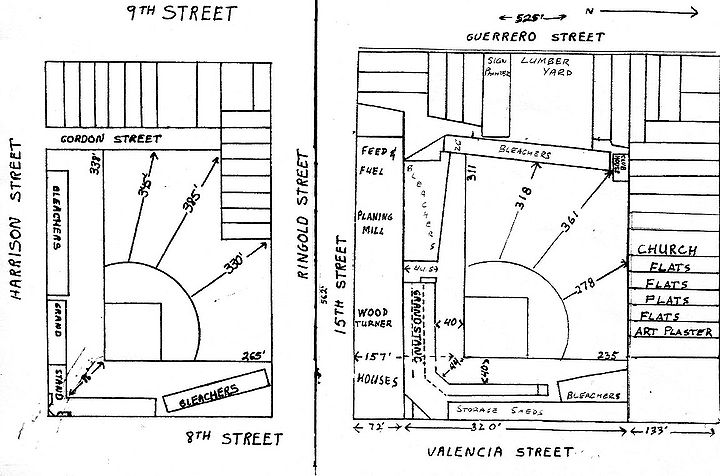

In the meantime, the management of Recreation Park intensified its efforts to obtain an undeveloped 35-foot strip of land between the third-base/left field seats and the developed properties along 15th Street from Hannah Crane. Mrs. Crane was a wealthy East Bay socialite and philanthropist who owned a 65’ x 472’ swath of land along 15th Street. (See FIGURE 2.) Sadly, Mrs. Crane’s generosity did not extend to San Francisco baseball. For all of his persuasive powers, Ewing failed to get her to yield any of her property for the good of San Francisco baseball.

As the rain continued, it was questionable whether the season would open on time. On March 26 PCL President Ewing officially postponed the opener one week to allow Recreation Park to dry out.

The right field bleachers were not ready as of the day before the opener. The Call wrote, “The workmen put the finishing touches on the ball park in spite of the showers. The slight sprinkle helped pack the soil and if weather conditions are all favorable, the field will be in grand form tomorrow afternoon.”

The long-awaited return of baseball to San Francisco was realized on Saturday, April 6, 1907. Seven thousand baseball-starved Seals fans witnessed their team blank Portland 6-0 nearly a year after their last scheduled game in San Francisco had been cancelled. (There was no mention in any of the game reports if the flag saved from Old Rec Park by Bill Johnson was raised.)

As the Seals coasted to their 5th consecutive PCL opening day triumph, the fans undoubtedly noticed that the seats were closer to the field than at the old park. The Chronicle had the best lipstick-on-a pig story of the year.

One feature of the new stands is the fact that the diamond is closer up than at the old park. If you want to sit behind the catcher, you are close to the plate, and if you want to sit to one side, you can be near enough to the first baseman to tell him what to do when you think he is in doubt.

Earlier suggestions that the new park was larger than the old one was wishful thinking. In terms of total area of the respective footprints, Old Rec Park was 134,750 square feet while the new park was 133,700 square feet. A difference of less than one percent may not seem like much, but it was quite significant; thus Ewing’s efforts to buy Mrs. Crane’s adjoining property.

At the time of the earthquake, Old Rec Park was the smallest of the six PCL ballparks. When play began in 1907, New Rec Park was the smallest of the four league parks. How small was it? The seats were from 20 to 46 feet closer to the playing field than previously: 40 feet vs. 60-86 feet. By comparison, foul territory (the area between the seats and fair ground) in Los Angeles, Oakland and Portland were 65, 60 and 65 feet respectively. (Today’s rules specify a 60-foot minimum.)

Ewing’s failure to secure the property from Mrs. Crane is significant in that the distance from home plate to Rec Park’s right field fence (actually the backs of houses fronting 14th Street protected by a 50-foot screen) was 235 feet—the minimum distance in the baseball rulebook for a legal home run.

If one word could describe Recreation Park, it would have to be INADEQUATE.

Big Rec at 15th & Valencia, c. 1924

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

Recreation Park was at its minimum and maximum at the same time. No more space could be allocated to the third base/left field seats without encroaching on the field, thus shortening the right field line and thereby making right field home runs illegal. Nor could the right field distance be lengthened without sacrificing seats, i.e. revenue.

Official attendance figures weren’t provided during this time. Newspapers would make eyeball estimates and sometimes report their guesses, but often not. Of course revenue came from fans in the seats. To enhance revenue, occasionally more tickets were sold than there were seats in the house (a common practice then even in the major leagues), resulting in the overflow crowd standing behind rope barricades in the outfield and in foul territory.

On Sunday morning the Seals inaugurated Oakland’s refurbished (and much larger than Rec Park) Freeman’s Park with a 4-3 victory over Portland in the first game of the split Sunday double-header. The afternoon game in San Francisco was witnessed by an overflow crowd of 10,000 Sunday worshipers, hundreds of whom stood behind ropes in the outfield as the Seals fell 4-1.

A month later San Francisco secured a rare forfeit victory over Portland when the Oregonians refused to walk to the ballpark because of a streetcar strike. This season-long transit strike would severely impact attendance at Rec Park.

Although Ewing never publically admitted it, he was absolutely desperate to have a ballpark in San Francisco for the 1907 season. Without baseball in San Francisco, the west coast’s premier city, the PCL would fail. We can’t know or even imagine the pressure that was on Ewing, but his choice (or forced choice) of such an inadequate site for a ball park speaks to his desperation.

His decision to build at 14th and Valencia and his failure to obtain the sought-after 35 feet from Hannah Crane made something better than the Valencia Street grounds a necessity.

A year earlier, the 8th and Harrison site had been cleared and was being used as a hot-meal feeding station for earthquake refugees. At that time the Chronicle, looking ahead to the city’s next ballpark, editorialized, “the present grounds are acknowledged to be too small for baseball. What San Francisco needs is an enclosed athletic field that will permit of any field or track contest. It should be large enough for a lacrosse game. It should also be constructed so that all the big football games could be accommodated. This sort of field would be a paying proposition, even during the closed season of baseball. Ground can be secured south of the Park.” The heyday of baseball at the Haight Street Grounds of the 1880s and 1890s were fondly recalled.

Recreation Park I was built in 1897 on land leased from the San Francisco and Pacific Sugar Company. As shown in the diagram of the site, (bounded by 8th, Harrison, Gordon and Ringold Streets with home plate at the corner of 8th and Harrison), with the exception of buildings in the northwest corner of the block (center field) the ballpark did not have to be shoe-horned into an already-developed block as was the case with new Rec Park.

The two sites can be compared side-by-side below:

Ball park schematics from BALLPARKS OF THE PCL by Larry Zuckerman

During the 1907 season, while Cal Ewing was handling administrative affairs as PCL president, the Seals were run by Frank Ish and Jack Gleason in the front office and Danny Long on the field. The Seals ended the 1907 season second in the four-team league with a 104-99 record. Los Angeles won the pennant and Oakland, under the guidance of Ed Walter, (Ewing’s surrogate for his Oakland interest) finished third.

1908-1912

THE SEASONS OF THE WOLF (# 1)

The 1908 season began with grass on Rec Park’s field and streetcars carrying fans to the turnstiles, though a paltry 6,000 showed up for the opener on Saturday April 4. As the season progressed the faithful endured early-season bad weather and equally poor Seals’ play. It was a forgettable year for the Bay Area teams; San Francisco and Oakland finished 3rd and 4th respectively in the 4-team Pacific Coast League. The next year manger Kid Mohler brought San Francisco its first PCL championship. Oakland continued its losing ways, finishing 5th in the now six-club league. Three weeks following the conclusion of the 1909, Cal Ewing stepped down as PCL President after leading the league for the past 2½ years. His two greatest accomplishments during his tenure were to add Sacramento and Vernon (a suburb of Los Angeles) to the PCL, and to repel the incursions of two rival leagues with expansion agendas.

During the post earthquake years that the PCL was reestablishing itself on the west coast, developments back east would have profound implication for the future of the PCL, the Seals and for Ewing. As Ewing moved up from leading a club to leading a league, an eastern baseball personality also made an upward career transition. Thirty-four-year old Harry Wolverton, a former major league third baseman, became the playing-manager of the Williamsport (PA) Millionaires of the Tri-State League in 1907. In his rookie managerial season, the popular Wolverton (also known as “Fighting Harry” for his quick temper), led the Millionaires to their first pennant, due no small part to his playing skills as well as his leadership ability. In 1908 Wolverton declined an opportunity to return to the majors to stay in Williamsport where he once again led his team to the Tri-State pennant.

This earned him a promotion from the Class B Tri-State League to the Class A (the same level as the PCL) Eastern League to play for and manage the Newark (NJ) Indians. He found himself in the untenable position of managing Joe “Iron Man” McGinnity, former New York Giant pitching stalwart, future baseball Hall of Famer and current owner of the Indians. The pitcher/owner and player/manager did not agree on pitching strategies and Wolverton was soon demoted and McGinnity took over field leadership as well as front office management.

In 1910 Ewing was back at the Seals’ offices on Valencia Street while his Oakland counterpart, Ed Walter, hired Harry Wolverton to manage the hapless Oaks, which hadn’t had a winning season since 1904. It would be Wolverton’s Herculean task to raise them from the dead.

On December 9, 1909 the Call introduced Oakland’s new field general:

In his prime [he] was one of the greatest third basemen the game ever knew. . . He is a big strapping fellow and always batted over .300. His only fault was his temper which got him into many scrapes.

By the second week of the 1910 season the Oaks were in familiar territory: the cellar. The doubly ignominious loss that put them there was Wolverton’s debut before Oakland fans at Freeman’s Park against their cross-bay rivals, the Seals. The Call chided, “The Oaks are running to cellar form again.” The return match between the two clubs on Sunday was before a full house that was rewarded with a 6-2 Oaks victory over the 1909 champs. Regardless, the early indicators were that the Oaks would have another abysmal season. As game after game was added to the Oaks’ loss column, the Call diagnosed their main malady as “repeated bonehead plays”.

As San Francisco and Portland battled for league supremacy, Sacramento came to the Bay Area to battle Oakland for the last spot. The Oaks had lost seven of their last eight, so it didn’t seem promising for Wolverton’s cubs. Unbelievably, Oakland went on a tear and won not just five of the seven games from Sacramento, but four of the next seven from San Francisco to knock them out of first place. The East Bay was so infatuated with Wolverton that a Freeman’s Park attendance record was set in a Sunday morning game against San Francisco followed by a sell-out at Recreation Park for the afternoon contest.

Before a full house at Recreation Park on May 22, Oakland defeated Portland to attain a record they hadn’t enjoyed since the fourth game of the season: .500. The next day’s double-header sweep of the Beavers gave Oakland a winning record for the first time since they were 2-1 on April 1.

Oakland’s improved play was the catalyst for making the 1910 pennant race the closest in PCL history. And the most volatile. With a winning record and, more importantly, a winning attitude, Wolverton’s charges were unstoppable. They played 21 games before losing two in a row. On Sunday June 12 another record Oakland crowd saw Wolverton’s Wolves defeat the Seals to claim second place. The SRO crowd that packed the outfield ten deep at the afternoon game at Rec Park saw Oakland continue its torrid pace by defeating the Seals and, once more, knock them out of first place.

Two days later the seemingly improbable yet inevitable came to be—Wolverton’s Oaks were in first place. The Chronicle had a banner headline: OAKLAND LEADS PACIFIC COAST LEAGUE.

The Call extolled Wolverton’s achievement:

The fans are forced to admire the wonderful fight made by the Oaks under the able leadership of Harry Wolverton who was imported for the express purpose of giving the Transbay city a winning team. The Oaks started one of the hardest uphill fights in organized baseball.

Reality immediately slapped Oakland in the face with a three-game losing streak, dropping them to 3rd place three days after being number one. But the entire PCL pennant scramble was beyond comprehension. In one week four different teams, including Oakland, led the league. In one day Portland went from first to fourth. Anything seemed possible. Or not impossible.

A return of bone headedness resulted in 7 consecutive losses and a plummet to 4th place. The frustration was too much for Wolverton who almost single-handedly caused a riot at Recreation Park arguing with the umpire. The Call scolded,

WOLVERTON AND OAKLAND PLAYERS CAUSE NEAR RIOT

Wolverton allowed his hoodlum instincts, which were so much in evidence at the start of the season to come to the surface.

At the midway point of the 1910 season the Oaks were in 5th place. For Oakland this was their usual post, but this time there was no shame. They had a winning record—unprecedented for this late in the season—and they were a mere 3½ games behind the leading Seals.

In August Wolverton’s steady leadership carried Oakland to second place behind the Seals. Never before had both clubs been in such heated contention and this produced huge crowds on both sides of the bay.

A come-from-behind Oakland win in the bottom of the 9th at Rec Park against Portland on August 10 elicited this Call tribute:

Yesterday the Commuters fought and tore and raged around the diamond, the fighting blood seemed to be boiling in the veins of every one of them. They were full of confidence and it was merely a question of [how they would win].

The next day another improbable victory brought Oakland into a virtual three-way tie for first with San Francisco and Portland. The Call splashed the banner headline

OAKLAND’S DASH FOR THE PENNANT IS THE SENSATION OF BASEBALL SOCIETY.

Game by game, Oakland and Portland separated themselves from the rest of the league, but neither could pull away from the other. Neck and neck the Oaks and Beavers kept up the pace. On September 5, with 64 games still to play, Wolverton equaled Oakland’s 1909 winning total—88—with a win over Sacramento. It also brought them dead even with Portland.

Taking five of nine from Portland in the next series at home gave Oakland the league lead. But once again reality slugged them, this time in Los Angeles where they lost the next three in a row, including a game lost by forfeit because of Wolverton’s temper. The Los Angeles Herald wrote:

Wolverton and others were guilty of rowdy tactics. They failed to leave the field within five minutes of being banished. Their threats to attack the umpire brought police onto the field, thankfully for Wolverton, before the outraged fans.

On September 20 Wolverton’s gang returned to San Francisco to play the Seals, who were now out of the race, winning four of the first five games. Calling it Oakland’s Greatest Baseball Crowd, the Call described the packed house in Oakland on Sunday morning.

Oakland never knew such a crowd as the one which crushed its way into Freeman’s Park. After the stands and bleachers had been packed to the suffocation point, the fans surged out onto the field and it was with difficulty that the place was cleared for action.

It was a day that the Chronicle described as “far from pleasant”. Nonetheless the Chronicle estimated the Oakland mob at 9,000 and 13,000 at the afternoon contest at Rec Park.

The Call sang the praises of the East Bay’s heroes for their 6-0 afternoon victory over the Seals: “They played a magnificent game of baseball . . . like three-time champions.” This was their 100th victory of the year.

They left for a week in Portland ½ game behind the Beavers. This would be the final meeting of the two challengers. Oakland lost three of five and precious ground, but a week later their three losses were overturned because Portland had used an ineligible player. Oakland was back on top.

Wolverton brought the Bay Area something it had never experienced before: a real down-to-the- wire pennant race. On October 15, with Oakland one game behind Portland, 5,000 were on hand at Rec Park “although it was bitterly cold and rain clouds hung low”.

The race seemed over after Portland won eleven in a row while Oakland gave away six of seven to the lowly Senators, but after three Oakland wins the Call expressed a faint hope: “The Oaks have come to life again. They are playing in a spirit that made them a serious contender a week ago.”

Two more wins elicited this Call headline on October 30:

OAKLAND TEAM MAKES SPLENDID RALLY AS SEASON CLOSES

“There is still a fighting chance for Oakland” was the Call’s rally cry as the season entered its final week with the Oaks’ last chance for a pennant resting on a series with the Seals.

The Oaks chased the Portland Beavers all the way to the third from the last game of the season before the race ended.

On November 7 the Call heralded:

LAST BATTER OUT IN THE COAST’S GREATEST BASEBALL SEASON

Harry Wolverton did more than could have been imagined, bringing Oakland 35 more wins than in 1909—the greatest rags-to-riches story in PCL history. He signed a contract for 1911 before returning to Philadelphia for the winter.

Six weeks into the 1911 season, after each club had played all the others, Portland was in the lead and would remain so through the first half of the year. Oakland had lost its two top pitchers (Walter Moser and Jack Lively) who had accounted for 63 of Oakland’s 1910 123 victories to the major leagues.

At mid-season Oakland couldn’t find the magic of 1910 and was fourth behind Portland, Vernon and San Francisco. Week by week it became a battle between Portland and Vernon. On July 24 Oakland and San Francisco switched places. Oakland would remain in third for the rest of the season while San Francisco would slip to fifth by the end.

Harry signed a contract to manage Oakland for a third year, but in November rumors spread that the New York Yankees were interested in the West Coast magician who brought Oakland its first golden age of baseball. On December 11 Harry Wolverton became the Yankee manager and the next day the Call blared: WOLVERTON ABANDONS OAKS FOR NEW YORKS. Great Leader Succumbs to the Terms Made by The Boss of Highlanders.

While Wolverton was the first PCL manager to manage in the major leagues, Oakland’s disappointment was palpable. The deal, which reportedly would give Wolverton far in excess of $10,000 per year plus a bonus for finishing first, second or third, was contingent on the Yankees (still occasionally called the Highlanders at this point in their history) giving Oakland a “satisfactory successor” to replace the miracle working Wolverton.

The “satisfactory successor” was Bud Sharpe, who had no managerial experience and only a brief major league career. His minor league career was notable only in that he was on the Newark Indians in 1909 when Wolverton was the manager.

Whether an Oaks fan or Wolverton follower, 1912 was not a year for the faint of heart. On April 23, when Harry savored his first sip of major league victory nectar, his former Oaks were leading the PCL with a 15-4 record. Harry’s first win, sadly, came after he had lost the first six games of the year and his Highlanders/Yankees were in last place. Harry would finish the season with what would be the worst record in Yankee history, 50-102.

On the west coast, Wolverton’s “satisfactory successor” was making the fans forget Harry. All season long the Sharpe-led Oaks battled the Vernon Tigers, neither team getting any significant advantage over the other. After two hundred games they were tied. This was more intense than Wolverton’s 1910 battle with Portland.

Coming into the final weekend of the season it was still undecided. On the final day of the season, with the race still up for grabs and both contenders playing double headers, the Call described the scene at the morning game in Oakland:

11,000 frenzied fans [the Chronicle estimated 12,000] prayed and hoped their team would win in Oakland. After the fans had packed the stand and the bleachers, they overflowed upon the field. Men, women and children huddled together along the fences, fighting for a chance to watch every movement of the rival players and cheering wildly for their favorites. Oakland never knew such a diamond event. They ought to mention it in the city’s history.

The Oaks led 5-2 going to the top of 9th. Then the Angels suddenly scored twice and had the tying run on second with one out. Two tense outs later with no damage done, 11,000 fans ran to catch the ferries that would take them to San Francisco and the last game of the season where the greatest crowd that ever has witnessed a game of baseball in San Francisco since the days of the historic Haight Street Grounds greeted the rival teams as they sauntered out upon the Valencia street lot. Cal Ewing estimated the mob at 18,000.

Two homers in the bottom of the first sealed it for Oakland. The Angels managed only two hits and no runs.

After 208 days and 203 games (201 for Vernon) Oakland won its first championship by one game: 120-83 to 118-83

The Call described the season’s physical and mental toll on Bud Sharpe, Wolverton’s “satisfactory successor”.

Bud Sharpe, the man who has guided the destinies of the Oakland club all the year, sat on the bench and watched his men as they won the pennant. He was powerless to do anything more than direct them. A nervous wreck, a shadow of a once powerful athlete, Sharpe twitched and squirmed until the men under his command had won the afternoon game and clinched the pennant. Then he heaved a sigh of relief. He will leave California in a day or two—probably forever.

The day before Sharpe and the Oaks had confirmed that doctors recommended he take off at least a year from baseball. The Call’s front-page headlined:

Oakland Wins The Coast League Pennant. World Series had nothing on Final Fight.

NEVER DID A COAST LEAGUE SEASON SEE SUCH A SOUL STIRRING FINALE

The Call saluted the champions:

Hats off to the Oaklanders and give them the credit that is coming their way. They won the pennant on the level. They played the winning brand of ball and showed their pluck and their fighting ability in the pinches. They had their ups and downs, and they triumphed in the end. More power to them.

On November 1, 1912, Ed Walter (still leading the Oakland club) chose Oaks catcher Honus Mitze to lead the team, a selection that was applauded by the fans. A Wolverton discovery, Mitze was brought to Oakland by “the great one” in 1910. He was a good defensive catcher and a good handler of pitchers though he was not a good batter.