Fisherman's Wharf

Historical Essay

The Passing of an Era

by Anika Okje Erdmann, published originally at fog-city.co

Fishermen's Wharf c. 1900

Photo: J.B. Monaco

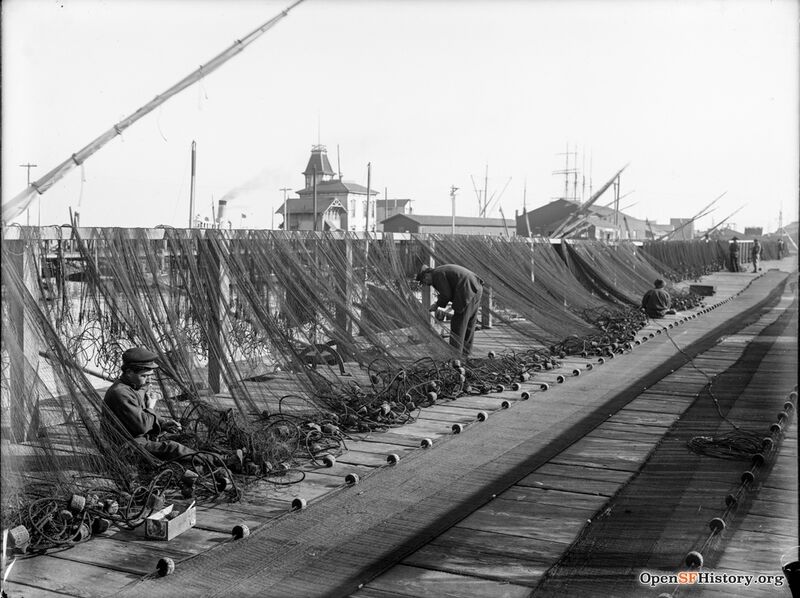

Fishermen mending nets near foot of Powell Street. Meiggs Wharf in the background, c. 1900.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp15.708

At end of Meigg's Wharf. View west toward Russian Hill. Smokestack of Selby Smelting works at foot of Hyde Street visible at right. Fishing Boats, men on pier mending nets.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org, Old Fisherman's Wharf_SF2-33 GGNRA-Wulzen GOGA 18480_wnp71.10091

Fisherman's Wharf, c. 1910.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp26.1464

The story of Fisherman’s Wharf began in 1900, when the state set aside the waterfront between the foot of Taylor and Leavenworth streets for commercial fishing boats. Previous docks for commercial boats had been at the foot of Vallejo and the foot of Union, but as San Francisco Bay shipping expanded, the fishermen were moved out of the busiest area to the present location. From the beginning fishermen sold parts of their catch to housewives, directly from their sailing craft, and some of them set up stalls on the piers and developed a regular market.

Then one enterprising fisherman had the idea of selling clam chowder across his counter to hungry patrons. Fisherman Tom Castagnola expanded the practice; he put in some benches and tables and developed the crab cocktail, a small portion of crab meat with a special sauce. Shrimp cocktail also proved a popular dish, especially during prohibition, when other kinds of cocktails where slightly more difficult to come by. He tried mixing crab with Thousand Island dressing and developed the “Crab Louie,” which in time became the Wharf’s most popular dish. Castagnola soon found it more profitable to sell his boat, buy his fish from other fishermen, and devote his full time to the store. Others did the same. The late Mike Geraldi, for example, abandoned a twenty six year fishing career, built a restaurant – Fisherman’s Grotto – took his sons into the business, and served the first complete sea food meals on the Wharf.

Several Wharf families also opened restaurants the Aliotos, the Sabellas, the DiMaggios.

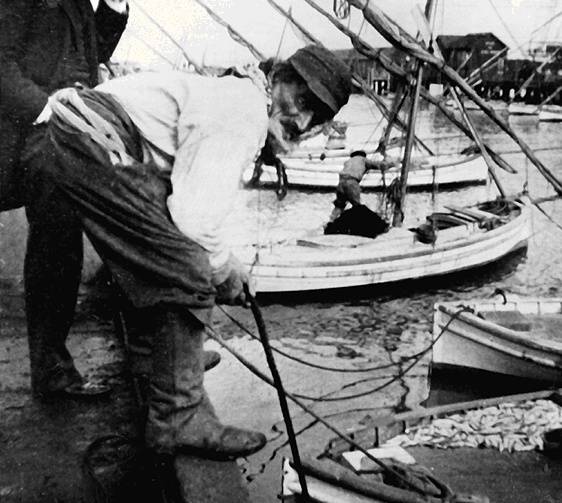

Italian Crab fisherman at Fisherman's Wharf

Photo: J.B. Monaco

Captain Calogero Alioto and his crew at Fisherman's Wharf in the 1920s.

Photo: courtesy Alioto family

The first break in the solid Italian tradition came when two businessmen named Gene McAteer and Bill Sweeney opened a restaurant in 1946 and, self-conscious about their names, labeled it “Tarenttino’s.”

The old era of the Wharf is passing. Fathers who once fished the Mediterranean and still speak is the accents of Southern Italy are being succeeded by sons who learned jive talk at Galileo High, served their time in the armed forces, and would rather watch television than play an accordion and sing of old Sorrento.

The Wharf is gradually growing less clannish; the days are gone when the entire fleet, loaded with fishermen and their big families, would sail on Sunday to some wooded Marin shore for a mass picnic. Many of the boats are still painted blue and white, the colors of the fishermen’s patron saint, La Madonna del Luime, but the only community custom which remains is the annual blessing of the fleet. On the first Sunday of October a long procession wounds down from Sts. Peter and Paul’s Church to the Wharf, where each boat is given the blessing by the priest.

Fishermen like Manilcalco are a vanishing tribe – a rugged breed of men who earn their living by working alone against the elements with little more than some basic equipment and their won skill and muscle. The one man boats are giving way to larger craft worked by a crew. The old timer who could look over the side in a fog, watch the waves’ angle of impact, and tell his location is being replaced by the younger navigator who knows how to use an electronic depth finder, charts, and direction finders. The fishermen who is alone all day with his thoughts on the rolling ocean is giving way to the youngster who likes to chat with other fishermen over his two way radio, contact the marine operator and phone his girlfriend or tune in on the local disc jockeys.

Fisherman's Wharf, c. 1950s, before touristification kicked in.

Photo: provenance unknown

Crabs at Fisherman's Wharf, 1950s.

Photo: Walter H. Miller

Crab nets stacked on Pier 45 in 2013.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

But crab fishing is not yet a safe or easy occupation. The fishermen still have to face storms and fogs and cold and rain. They still go to work in the middle of the night, and their boats move out the Golden Gate before dawn in a long parade, the lights flickering across the dark surface of the San Francisco Bay like the beacons of some phantom fleet.

The San Francisco Bay and its offshore approaches are their life and livelihood and will continue to be, as long as crabs can be hauled from the ocean floor and the leaping silver salmon rise to the bait.

Why do you think they call it Fisherman's Wharf?

Photo: Brett Reierson

Fishermen working with cargo.

Photo: courtesy Jimmie Shein

Fisherman's Wharf in 1956.

Photo: Russ Moore

Fisherman's Wharf

by Chris Carlsson

Fisherman's Wharf is one of San Francisco's most famous sites, a must-visit for most tourists in the 21st century. In fact, San Francisco was home to a large fishing fleet from its mid-19th century beginnings all the way to the late 20th century. Great efforts were made in the 1960s and '70s to save the working part of Fisherman's Wharf from being completely overrun by ticky-tack tourist shops and hotels, even while the Port of San Francisco sought to facilitate the development of tourism as a way to offset the loss of shipping after the 1960s.

View from northern end of Pier 45 back at Fisherman's Wharf, 2013.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Today's Pier 45 state-of-the-art fish processing facilities are partly thanks to funding that followed damages during the 1989 earthquake, but are also thanks to the diligence of Port and City officials who remained committed to saving the historic working fish industry on the northern waterfront. Herring, salmon, crab, and sports fishing are the primary businesses of the remaining fishing fleet, though traditional Italian family names like Alioto and Sabella still dominate the area's old restaurants and shops.