Mission Rebels in Action

Historical Essay

by Ethan Asher, 2021

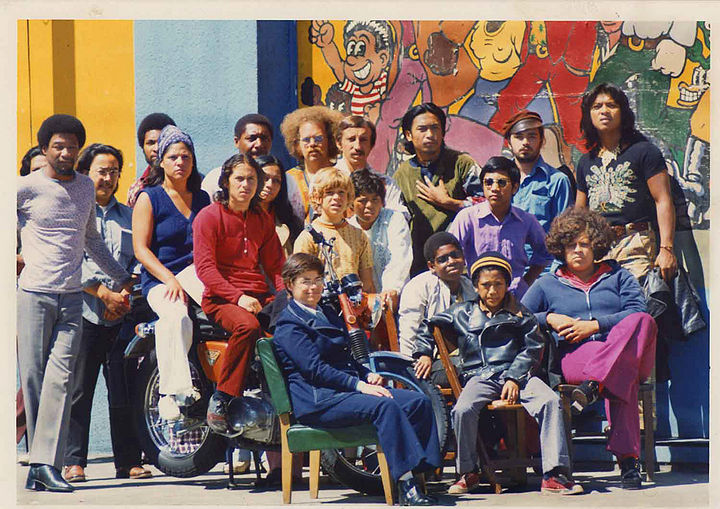

Mission Rebels, c. 1970.

Photo: El Tecolote archives

Throughout the 1960s San Francisco’s Mission district saw a dramatic upswing in grassroots organizing and activism. The Mission Rebels was founded in 1965 by “Rev.” Jesse James. The Rebels were a group of mostly high school and college-aged young people from the Mission, working with James and a host of adults to advocate for and provide job placement and educational programs, as well as to do general community work. The Mission Rebels’ tactics were known to create tension with other community organizations and unions; despite this, the Mission Rebel students successfully ran an organization which for years provided hundreds of low-income students with counseling and educational services, trained teachers to work in inner-city schools, and provided safe community space for hundreds of young people.

In a 1966 KPFA interview with Jesse James and several other Mission Rebels students and staff, done about a year after the Rebels had gotten started, James shares that one night he’d been approached by two teenagers asking him to buy them alcohol, after he’d recently worked to turn his own life around.(1) James understood that often young people felt like adults were there to let them down, or just say no, so he asked those two boys what they “really wanted.” The boys' overwhelming response that what they really wanted were better jobs, better opportunities, and simply for adults to care about their problems, which led them to found the Mission Rebels.(2)

James had grown up in Harlem, where he dropped out of school at an early age, mainly due to challenges with drug addiction. He was released in 1964, after spending 15 years in a New York state prison for his involvement with armed robbery. After his release, he started to work with David Wilkerson who ran an organization called Teen Challenge, an evangelical group that worked with at-risk youth in New York. James described the experience as life changing, and was eventually sent by Wilkerson to open a chapter of the organization in San Francisco, bringing him to the Bay Area. He left the organization following disagreements over his mentoring style, but was able to learn from the experience and use his expertise from both the streets, and Teen Challenge to build up the Mission Rebels.(1)

In 1966 the San Francisco Chronicle said the Mission Rebels were “staging a very attractive rebellion.”(2) The group had received over $80,000 in grants from the City and the new Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, in part for their mission of helping place high school students in part time apprenticeships and jobs as a tool to “prevent dropouts.” A wealthy individual in the Mission had donated a three-story former warehouse on South Van Ness Ave. to the group, which recruited college students from the neighborhood and local college professors to offer classes in typing, art, drama, and more subjects.(2) The building hosted dances and small parties every Saturday night, where every young person in the community was welcome—and often showed up. While the Rebels didn’t restrict access by race, the organization, like the Mission, was made up primarily of Black and Latino youth. At the time of the radio interview they had about 350 regular participants in the programs, with most classes having 40-50 students depending on the night. The key to getting young people engaged and excited about the organization was to let them lead it, as their Board was made up of 5 adults and 7 students, and almost completely directed by youth.(2)

Much of the group's initial focus was on improving the employment opportunities for young people in the Mission. Over 90% of the students involved in the Mission Rebels were characterized as “at-risk.”(2) The adults in the Rebels worked with local businesses, community leaders, and employers to place students in apprenticeship programs, prepare employers for working with Mission youth, and fight racist and ageist ability and employment tests.

From 1966 to 1974 the Federal Government implemented the Model Cities Program, designed to fund programs which fought urban poverty around the country.(3) In 1967, following previous redevelopment programs in the Western Addition district, which displaced many Black residents and razed entire neighborhoods, the organizations of the Mission District banded together. Their initial goal was to prevent two new high-density towers from being built on 16th and 24th streets, near the BART Mission expansion.(4) These organizations pursued collaboration after this initial success, and formed the Mission Coalition Organization (MCO). Their goal was to be recognized as the collective voice of the neighborhood, and responsibly distribute funds from the Model Cities Program.(3) Some organizations, namely the Mission Rebels as well as the Mission Tenants Union, had disagreements over the tactics and control of the MCO, taking grievance with larger, more powerful organizations wielding control over the Model Cities Fund.(5)

At the first MCO convention in October 1968, the Mission Rebels took over the stage and sound system in front of almost 700 organizers, admonished the convention, and proceeded to nominate their own slate of leaders.(6) The group employed this radical tactic to make a statement about the welfare system and its perceived tendency to cause additional harm, beyond just inefficiency. The conflict was only partially resolved by keynote speaker Cesar Chavez, who appealed to the group in an attempt to quiet any infighting. Following Chavez’ speech, Jesse James again took the floor and called out the leaders of the convention; however the vast majority of the 60 organizations sided with the MCO establishment. The Rebels remained in opposition to the MCO, and did not ultimately support the efforts of the coalition, but did continue their work on parallel issues in the neighborhood.

In addition to their work on employment, the Rebels are remembered for their teacher training program. In the Spring semester of 1969 Derrick Hill, the head counselor of the Rebels, offered a class through the Experimental College of City College of San Francisco for their staff and professors.(7) The course included seminars with gang members and other guest speakers, and was designed to expose the staff to the life of youth in the city at the time. After receiving positive feedback, the Rebels received grants from both the City’s Economic Opportunity Council, and the Education Professions Development Act (EPDA) to expand a Teacher Education Institute run by the Rebel students and adults into the summer of 1969. The institute paired up Rebels youth with teachers and empowered the young people to immerse the teachers in the reality, both good and bad, of the neighborhood.

The Mission Rebels played a critical role in the lives of young people in the city, and their work coincided with an overall increase in community mobilization around the Bay Area, especially among students. In 1967 the Black Student Union (BSU) at San Francisco State College began to organize for increased admission of Black students and a department for Black studies. The conflict between Black students and the University escalated, and by 1968 students from the BSU, Latino student organizations, and the Asian student group joined to form the Third World Liberation Front. They actively organized for their collective demands at San Francisco State and UC Berkeley, and the organization integrated into the growing national movement for racial equality.(10)

The Mission Rebels stayed active through the 60s and into the early 1970s, however the departure of Jesse James in late 1968 due to personal struggles with alcoholism and drug addiction weakened the leadership of the group.(1) While the rebels are no longer an active force in the city, their impact is still being felt. In 2007 then-Mayor Gavin Newsom formally recognized the work done by Horizons Unlimited, a community group that serves mostly Latino residents in San Francisco. The groups’ youth service and focus on employment programs has been credited as an outgrowth of the Mission Rebels program and structure. The Mission district has seen enormous change in the decades since the Rebels, but their legacy lives on.

Notes

(1) Taylor, Michael. [ www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Rev-Jesse-James-street-tough-turned-youth-2663448.php “'Rev.' Jesse James —Street Tough Turned Youth Advocate.”] SFGATE, San Francisco Chronicle, 21 Jan. 2012

(2) “A Groovy Rebellion.” Created by Al Silbowitz, KPFA, 18 Nov. 1966.

(3) “The Truth Behind MCO: Model Cities--End of the Mission” Basta Ya!, Nov. 1970

(4) Marti, Fernando. [static1.1.sqspcdn.com/static/f/633596/9137878/1288129554673/Mission+District+History.pdf?t The Mission District – A History of Resistance]. Asian Neighborhood Design, Dec. 2006.

(5) Carlsson, Chris, and Lisa Elliott, editors. Ten Years That Shook the City: San Francisco 1968-1978.

(6) Sandoval, Tomas. “MCO and Latino Community Formation.”

(7) DeNevi, Don. “The Mission Rebels As Trainers of Teachers.” Peabody Journal of Education, vol. 47, no. 5, 1970, pp. 286–289. JSTOR. Accessed 23 May 2021.

(8) Welch, Calvin, and Hank Chapot. “Los Siete.”

(9) Caldwell, Earl. “Coast Radicals Rally Behind 6 Latin Youths on Trial in Slaying of Policeman.” New York Times, 11 Oct. 1970.

(10) Strike Chronology