Workingmen’s Party of California

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

Rioting workers at site of Old City Hall, today's Main Library, in Civic Center

Image: Robert Chandler, via "Chinatown Squad" (click 'books' link) by Kevin J. Mullen

Ralston’s resignation as bank president came on the heels of a run on the bank that had become a virtual panic. At the same time that the Bank of California closed its doors, silver mining stocks fell sharply. Many who had succumbed to the mania for silver stock speculation lost heavily. By 1876, seven thousand San Franciscans received assistance from the city’s benevolent associations. The following year the nation plunged into a depression, compounded in California by declining yields from the Comstock and by a drought that caused the failure of the grain harvest. This, in turn, reduced the need for labor both for harvesting and for loading on the docks. Unemployment affected at least 15 percent of the city’s work force, perhaps more. In July 1877, a railroad strike in the east and announcement of wage cuts for California railroad workers prompted a mass meeting sponsored by the Workingmen’s party of the United States, a small socialist group. Held on the “sand lots”—open, sand-covered building sites near city hall—the meeting attracted eight thousand. Before long, the socialists lost control of their meeting and the crowd became a mob, roaming the city, attacking Chinese laundries, and beating those Chinese unfortunate enough to come within the mob’s reach.(17)

Anti-Chinese Antagonism

Antagonism toward the Chinese did not spring full-grown from that mob in July 1877. On the contrary, it had developed and gathered force for more than two decades. State legislation aimed at Chinese miners appeared in 1855. With the increase in unemployment following completion of the transcontinental railroad, anti-Chinese meetings took place on San Francisco sandlots as early as 1870. “Anticoolie” organizations appeared at about the same time, sponsored initially by the Knights of St. Crispin, an organization of shoemakers. San Francisco public officials responded to this growth of anti-Chinese sentiment by passing a series of discriminatory ordinances. They closed down the Chinese school but denied Chinese children access to the public schools. They defined the carrying of baskets on a pole across the shoulders as a misdemeanor, an action aimed at Chinese peddlers. They required all lodging houses to have 500 cubic feet of air for each resident and made tenants equally culpable with landlords for violations. Police never enforced the ordinance outside Chinatown, but enforcement in Chinatown soon produced such crowding of the city jails as to put them in violation of the ordinance. Supervisors thereupon passed the “queue ordinance,” requiring that the hair of all jail inmates be cut to within an inch of their scalp (depriving the Chinese of their queues) in an effort to encourage payment of a fine rather than serving a jail term. Mayor William Alvord, elected as a candidate of the Taxpayers' and Republican parties, vetoed the queue ordinance in 1873 when it first passed; Mayor Andrew Jackson Bryant, a Democrat, signed it into law in 1876. Another 1873 ordinance levied stiff license fees on laundries that made deliveries on foot, a measure intended to harass Chinese laundry operators. Supervisors passed this ordinance over the mayor’s veto. In 1876, rising unemployment again brought mass meetings aimed at the Chinese—the largest drew twenty-five thousand people—and a revival of the anti-coolie clubs. Just as in 1870, these brought in turn municipal actions aimed at pacifying the citizenry by enforcing the cubic air ordinance, reviving the queue law, and discriminating against Chinese laundries in the granting of laundry licenses.(18)

By July 1877, mass meetings at which speakers declaimed against the supposed evils of Chinese immigration had become staples of San Francisco life. The appearance of an anticoolie club at the socialists' rally in July 1877 surprised no one, but the riot that followed added a new element. Many in the mob knew that in Pittsburgh a crowd recently had put the torch to cars and buildings of the Pennsylvania Railroad. In San Francisco, the mob tried to burn Chinatown; they had been told for a generation that the Chinese caused low wages and unemployment. Although the mob failed to reach their objective, they frightened the city's commercial and political leaders. The next day a large group of the city’s business elite met with the mayor and police chief. William Coleman, leader of the Vigilance Committee of 1856, took the chair. Mayor Bryant announced that city police could not cope with the emergency, and Darius O. Mills, head of the reorganized Bank of California, proposed a Committee of Safety under Coleman’s leadership. Faced with illegal actions by a mob, the city’s commercial leadership responded as it had twenty years before—it undertook extralegal action of its own. The committee rapidly enrolled 5,500 members, collected more than 2,000 rifles and carbines, and secured pledges of $75,000; Coleman also had 6,000 hickory pick-handles converted into impromptu police clubs. After patrolling the city for a few days, the Pick-Handle Brigade disbanded, considering its immediate work complete.(19)

Denis Kearney and the Workingmen's Party

Denis Kearney

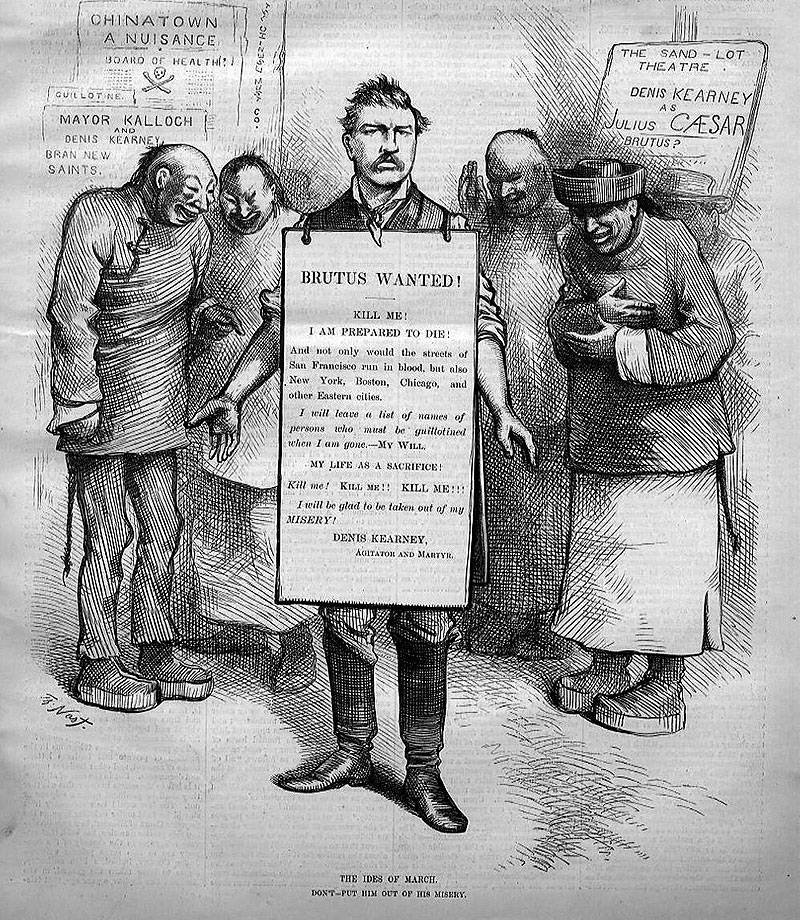

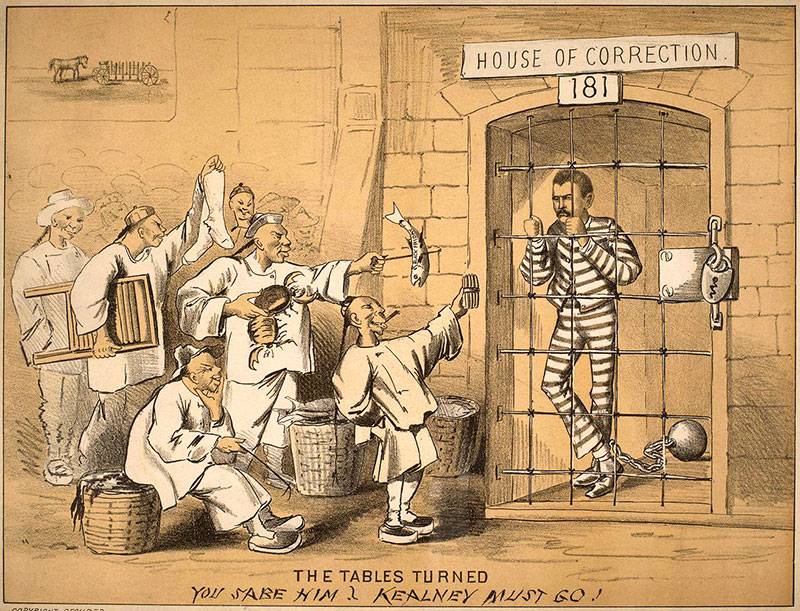

A month later, Denis Kearney, one of the members of the Pick-Handle Brigade, tapped the emotions that had motivated the July mob in order to build a political movement with himself at its head. Kearney, an Irish-born drayman, later stated that he had no sympathy with the July meeting because he was “opposed to strikes.” Drawn into politics, by his own account, because the deplorable condition of city streets made his draying business difficult, in August he took a leading role in the formation of the Workingmen’s Trade and Labor Union of San Francisco, a group intended initially as a “price club.” The organization expanded in October as Kearney harangued crowds at sandlot meetings, his message usually the same: the rich used the Chinese to drive down wages, workingmen suffered from both the millionaires atop Nob Hill and their minions in Chinatown, monopolies must be destroyed, and—always his closing—“The Chinese must go.” Not the first to advocate burning Chinatown or destroying the docks where Chinese immigrants entered San Francisco, Kearney repeated slogans long popularized by members of the city’s political establishment. Kearney, however, tied anti-Chinese rhetoric to attacks on the city’s business elite and gathered huge crowds who seemed eager to do his bidding. The police repeatedly arrested him for inciting to riot, and martyrdom increased his fame. By early 1878, the Workingmen’s Party of California (WPC) had become a major political force, both in San Francisco and elsewhere in the state.(20)

Denis Kearney presented as martyr for the cause in contemporaneous editorial cartoon, c. 1878

The WPC reached the height of its state power in mid-1878 and remained a potent force in city affairs through the end of 1879. In January 1878, the new party elected its candidate to fill a vacant assembly seat across the bay in Alameda, won another assembly seat the next month, swept municipal elections in Sacramento and Oakland in March, and scored victories in other municipal elections in April and May. In June, the entire state voted to elect delegates to a constitutional convention. Throughout the state, Republican and Democratic party leaders coalesced on a joint slate, termed “nonpartisan” but in reality bipartisan and anti-WPC. Nonpartisan delegates formed the largest group in the convention, numbering eighty-one of the 152 delegates; the WPC counted fifty-one, and the rest wore various party identifications. Of those not aligned with the WPC, a number affiliated with the Grangers, who held antimonopoly views similar to those of the WPC. Although the WPC and the Grangers might have formed a majority, they achieved no real coalition. The convention met for some five months and produced a document that Henry George described as “a mixture of constitution, code, stump-speech, and mandamus.” George felt it was “anything but a workingman’s Constitution” because it disenfranchised transitory workers, levied a poll tax, and entrenched vested rights in land. Conservative groups, however, reacted with alarm to provisions on taxation and corporations. The new constitution also contained many restrictions on the Chinese and on the right of corporations to employ Chinese workers, sections quickly declared contrary to the U.S. Constitution and hence void. The ratification election in the spring of 1879 saw intense efforts on both sides, with the WPC and Granger groups working for approval and business groups and traditional political leaders opposed. Large majorities favoring ratification in agricultural sections of the state overcame opposition of urban areas, and the constitution took effect.(21)

Kearney is taunted by caricaturized Chinese while he's incarcerated for inciting riots against the Chinese population...

Image: The Wasp

September 1879 saw elections for both state officials and San Francisco city officers. The WPC and the Republicans shared in the victories statewide, the Republicans taking the governorship and the WPC candidate winning as chief justice of the state supreme court, the San Francisco city election, like so many events in the late 1870s, seemed almost a return to the chaotic 1850s when politicians settled with gunshots controversies they could not resolve through politics. The WPC chose Isaac S. Kalloch, pastor of the Baptist Metropolitan Temple, as its candidate for mayor. His nomination provoked strong opposition from Charles de Young of the Chronicle, which had previously been the only paper in the state even mildly supportive of the WPC. De Young published repeated attacks on Kalloch, likened him to “an Unclean Leper,” revealed he had once stood trial for adultery, and added other charges. Kalloch used his pulpit to reply in kind, labeling the de Young brothers “moral lepers [leprosy seemed a popular charge] . . . hybrid whelps of sin and shame, . . . [and] hyenas of society.” He brought the de Youngs’ mother into the fray by referring to their “bawdy house breeding” and “guttersnipe training.” The next day Charles de Young shot Kalloch in the chest and side, but the minister survived and won the election from his sickbed. Undaunted, de Young published a pamphlet repeating charges of Kalloch’s licentiousness, and in late April 1880 Kalloch s son shot and killed Charles de Young. A jury acquitted young Kalloch when a witness—later convicted of perjury—claimed de Young had fired first. Kalloch. as mayor, faced a hostile majority on the Board of Supervisors (Republicans held three-quarters of the seats), and by the time he left office, the WPC itself had died.(22)

The WPC and the Voters

During its heyday, the WPC commanded the loyalty of half the voters in San Francisco. James Bryce ascribed this success to support

by the Irish, here a discontented and turbulent part of the population, by the lower class of German immigrants, and by the longshore men, also an important element in this great port, and a dangerous element (as long ago in Athens) wherever one finds them.

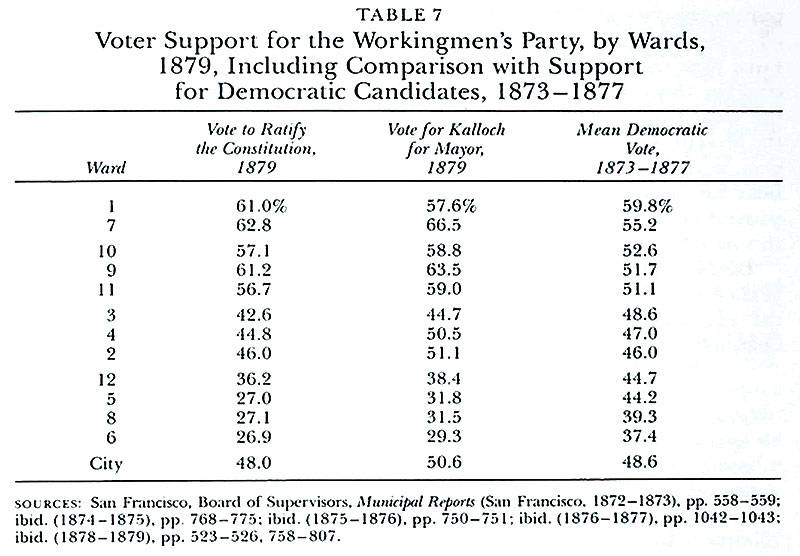

Bryce added, however, that Kearney also drew support from “the better sort of working men, clerks, and small shopkeepers,” no doubt the group Henry George referred to when he wrote that Kearneyism attracted “people who never joined the clubs or visited the sand-lot . . . people who were so utterly disgusted with the workings and corruptions of old parties as to welcome ‘anything for a change.’” The Democratic party virtually disappeared in San Francisco—“scarce a grease spot was left to mark its place” according to one prominent Democrat—as the WPC seized the support of normally Democratic voters. Bryce, George, and others agreed that the WPC benefited greatly from the attention given it by the newspapers, especially the Chronicle, which supported the movement until Kalloch’s nomination.(23)

If the vote to ratify the constitution and Kalloch’s vote for mayor are used to analyze the base of WPC support among the voters, patterns emerge that verify the observations of both Bryce and George. Table 7 summarizes the WPC strength by ward and also includes the mean Democratic vote for 1873-1877.(24) The WPC clearly drew the bulk of its support from the same areas that had given the Democrats majorities before 1879, and the WPC did poorly in areas that had been—and remained—Republican. In nearly every instance, however, the WPC provoked a more cohesive response than had the Democrats. In working-class areas along the waterfront and south of Market Street, the WPC received a larger share of the vote than had the Democrats; in middle-class and upper-class areas, the WPC did worse. The sharpening of class antagonisms by Kearney cut through some of the non-economic bases for party affiliation that had previously operated.

Table 7, showing Workingmen's Party vote distribution.

By August 1881, Kearney himself admitted that “there is no Workingmen’s Party now.” The WPC plunged to its nadir as rapidly as it had soared to its zenith. The reasons for the party’s decline include the Kalloch–de Young shootings, splits within the WPC leadership over party policy and over alliance with the national Greenback party, and general disappointment over the outcome of the WPC agitation. Kearney, most observers agreed, lacked the ability to build a permanent organization, and, equally serious, he lacked the depth to propose and implement measures that would relieve the economic suffering that gave him his South of Market base. Henry George, as early as 1880, understood that Kearneyism posed no serious threat to the political order. He found the new constitution “destitute ... of any shadow of reform which will lessen social inequalities or purify politics.” WPC candidates, he felt, “have been no more radical than the average of American politicians.” Most important, Kearneyism contained no viable alternative to the economic and social factors that produced both the July Days and Kearney. The WPC proposed instead, George wrote, “merely the remedy which their preachers, teachers, and influential newspapers are constantly prescribing to the American people as the great cure-all—elect honest men to office and have them cut down taxation.” At the same time that the WPC suffered schisms and the younger Kalloch stood trial for shooting de Young, the elder Kalloch faced a hostile majority on the Board of Supervisors, the economy of the city slowly improved, and the level of unemployment fell. The WPC had fed on the distress of depression, and the unemployed and destitute had thronged to the sandlots to hear Kearney speak. With the return of more prosperous times, Kearney proved unable to attract the crowds of earlier days, and the WPC lost even this base.(25)

Despite the sound and fury of Kearneyism and the WPC, within two years it signified but little for the city’s politics. Bryce expressed surprise at the ease with which such volatile political currents returned to familiar channels:

The game of politics between the two old parties goes on as before. . . . The city government of San Francisco is much what it was before the agitation. . . . After all. say the lawyers and bankers of San Francisco, we are going on as before, property will take care of itself in this country, things are not really worse so far as our business is concerned.

“Neither,” Bryce continued, “are things better,” and for a time in the 1880s, they became worse.(26) San Francisco politics during the 1880s differed from previous patterns in one major regard: power was concentrated more than before (or after) in the hands of one person, Christopher Augustine Buckley.

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 6 “Politics in the Expanding City, 1865-1893”