Politics in the Early 1890s

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

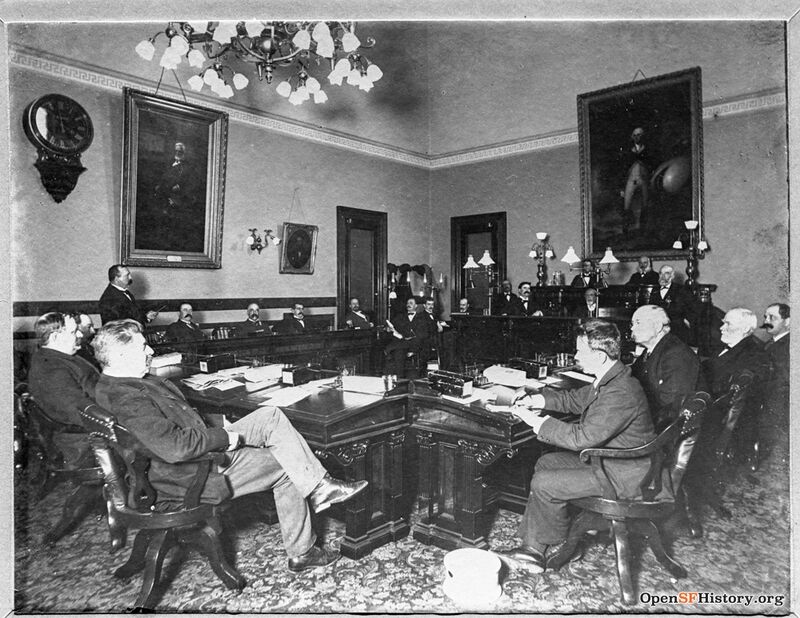

City Hall wheelin' and dealin' c. 1895.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp37.04053

In comparing the patterns of voting during the early 1890s with those before and after, the most obvious difference lies in the strong showings of independent or third-party candidates. Beginning in 1888 and continuing through 1896, C. C. O’Donnell ran as an independent candidate for mayor; he secured about 30 percent of the vote on his first four tries, and he finished a close second on several occasions. A forceful speaker who had taken a prominent part in the WPC throughout its existence, O’Donnell drew his support largely from South of Market, the Mission, and the northern waterfront, all districts where the WPC had done well and all with substantial numbers of workers and Irish. O’Donnell’s strong showing substantially reduced support for the Democratic candidate to the point where O’Donnell led the Democratic candidate several times. Not until 1896, when James Phelan (Irish and Catholic) carried the Democratic banner, did the Democrats recover their base South of Market and in the Mission. That year, O’Donnell did poorly in those areas, but Phelan got more than half their votes.(39)

Third-party candidates won the mayoralty in 1892 (when the secret ballot was used for the first time) and in 1894. In 1892, Levi R. Ellert ran on the Nonpartisan ticket, a group dominated by businessmen from both major parties. Ellert won on the strength of support from the Western Addition, Pacific Heights (where he took half the total vote in a four-way contest, his best showing), the upper-middle-class residential district just west of the central business district, and the more middle-class areas of the Mission District. The Morning Call characterized Ellert’s support as coming from “the precincts where the better class of people have their homes.” O’Donnell led South of Market, in the Mission, and downtown, the same areas where the Democratic candidate made his strongest showing. The Republican candidate did best in the same areas that gave Ellert his margin of victory. Similar patterns prevailed in 1894. Adolph Sutro, well known both for his large landholdings in the western part of the city and his recurring fights with corporations, became San Francisco’s first Jewish mayor by defeating Ellert (running for reelection as a Republican), who placed third behind O’Donnell. Elected as the candidate of the Populist party, Sutro ran most strongly in the same areas that had elected Ellert two years before but added considerable support in working-class areas—the Mission, the northern waterfront, and South of Market, where he matched or even slightly exceeded O’Donnell’s vote. James Phelan, running in 1896 as a Democrat and Citizens’ Nonpartisan, swept to victory with a coalition that cut across these previous patterns. His best showings came in upper-class and working-class areas—Pacific Heights and the northern waterfront (he got 60 percent or more in both) and South of Market and the Mission (where he got more than half the votes). Phelan ran more poorly in the Western Addition and the residential area west of the central business district, middle-class areas where both Ellert and Sutro had done well. Even in those districts, however, Phelan ran well ahead of his Republican opponent (his closest challenger), securing margins as large as two to one. Buckley’s last hurrah as a political leader came that year; his candidate, nominated by the Populists and Anti-Charter Democrats, ran fourth in all parts of the city, far behind Phelan both south of Market and in the Mission.(40)

The ticket splitting of the early 1890s resulted in part from the nature of the issues and candidates and in part from the disarray of the dominant Democrats. Another important element was the new Australian (secret) ballot law, which guaranteed that every voter could choose among all the declared candidates without having a party retainer peering over his shoulder. The 1891 legislature approved the new ballot law only after a long battle, led by the Democrats and the San Francisco Labor Council. Republican leaders in the legislature delayed until virtually the last minute, then finally yielded to the pressures from the minority Democrats and the virtually unanimous press. The Australian ballot law was an important chink in the armor of the parties. Now a corps of party workers did not need to stand outside every polling place. A candidate with only a weak party organization but a high degree of personal popularity—Sutro is a good example—could win overwhelmingly even though the remainder of his party ticket had no significant support. Even though the Australian ballot law helped to elect Sutro in 1894. in most other ways parties remained as formidable as before. Parties still controlled access to office, through the primary and convention system, and the Australian ballot law did not apply in those intraparty affairs—witness the devious methods used by reformers and regulars alike in 1892. Even the use of secret paper ballots in a party meeting could produce surprising results; in the 1895 Democratic general committee meeting, the 292 committee members present cast 338 ballots, 184 for the reform candidate and 154 for the candidate of the regular faction.(41)

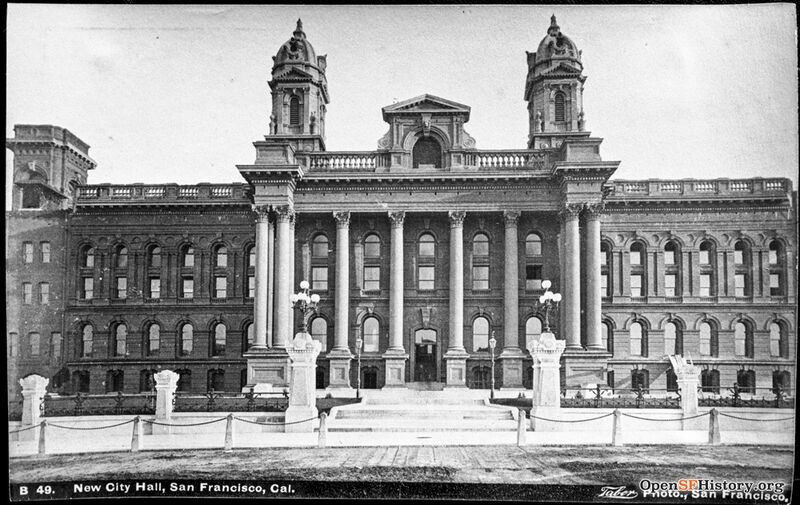

View south from McAllister towards the then-main entrance of Old City Hall, late 1880s.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp37.04042

With a few exceptions, basic patterns of politics after the defeat of Buckley remained much as they had been before. Much of the process of campaigning still consisted of identifying and mobilizing one’s supporters, and South of Market boardinghouses still formed potent centers of political support. For South of Market residents, politics remained a diversion, a social activity, and a potential channel of mobility. Neighborhood political clubs still provided, on occasion, “clam bakes, bull-head breakfasts and the like” and still sought to act as “an employment agency on the most wholesale scale possible.” Chris Buckley had vividly demonstrated how politics could lift a stonemason’s son to riches, and many working-class young men knew that through campaign work “a good fellow could gather in a few simoleons without overtaxing his strength.” Politics could still produce patronage positions for the fortunate few. Newspapers had publicized the fact that when Buckley’s slate entered city hall in 1883, his father became principal office deputy for the superintendent of streets, his nephew entered the police force, a cousin by marriage was named chief assistant to the head of the carpenter shop in the school system, and his bodyguard became superintendent of the House of Correction.(42) Politics, for the South of Market working class, could also be an instrument of protest, as shown by the WPC in the late 1870s. Although South of Market provided the bone-and-sinew of party organization, direction came largely from lower-middle-class businessmen: saloonkeepers like Buckley, Higgins, and Maguire, hotel clerks like McNab, draymen like Kearney.

Businessmen and professionals of the upper-middle and upper classes seem rarely to have understood the political value of clam bakes and bullhead breakfasts. Most would have been awkward and uncomfortable performing what Martin Kelly described as essential duties in his work:

He must swagger into a saloon, slap down a twenty, call up the house and tell the bar-keeper to freeze onto the change. . . . He must dispense the cold bottle and the hot bird. ... He must never forget his lowly retainers, for whom he must find jobs, kiss their babies, and send them Christmas presents.(43)

Nor did the residents of Nob Hill or the Western Addition value politics as a channel of mobility. Most of them already had a greater degree of material prosperity and higher social standing than they could possibly achieve through politics. Nonetheless, some of them did take part in politics. For some, participation came grudgingly and out of a sense of party loyalty. In 1880, George Hearst bought the Examiner to provide the city with a Democratic daily newspaper, and he subsidized it continually for the next several years.(44) For some, as well, there were abstract principles and issues that usually reinforced their party loyalties and often kept their political attention fixed on Washington and Sacramento.

Beyond and in addition to party loyalty and principle, businessmen and professionals seem to have entered politics for three main reasons: a quest for preferment, a defense of their enterprises, and a desire for status. Many of these directed their attention away from city politics. Quests for preferment took the form of subsidies (usually state or federal), franchises (at any level), or contracts. Such preferments had the potential for turning modest fortunes into sizable ones. The Big Four stood as the leading examples, but others could be found without effort—the Slosses and Gerstles of the Alaska Commercial Company; Claus Spreckels, who secured important concessions from King Kalakaua of Hawaii and turned them into a sugar fortune; or Adolph Sutro, whose tunnel franchise in the Comstock made him a wealthy man. Once secured, preferment had to be protected against those who might overturn it. Regulation was virtually nonexistent, but threats of regulation or even government ownership posed constant dangers. The status of high office, especially in the U.S. Senate, allowed one to combine party loyalty, high principle, quest for preferment, defense, and membership in the nation’s most exclusive club. If competition in California became too intense, there was always Nevada, a route to the Senate taken by Francis G. Newlands, who moved to Nevada in 1888, was elected to Congress in 1892, and to the Senate in 1903, following in the footsteps of his father-in- law, William Sharon.(45)

For members of San Francisco’s upper class who sought preferment, had to defend their turf, wished to demonstrate their party loyalty, or hoped for the status of high office, the customary method of participating in politics in the late nineteenth century was not the hustle of South of Market politics, but the rustle of greenbacks and the clink of gold. One English visitor to the city in 1877 wrote that “it would, in reality, be no exaggeration to state that men (voters) are standing on the public sidewalk, with the price of their votes marked on their sleeves.’’ Abraham Ruef, a young lawyer cutting his political eyeteeth in 1890, recalled that in that election “five dollars was said to be the ruling rate for single votes [for Stanford-pledged legislators], though as high as ten dollars was paid for voting the ‘straight’ tickets.” Officials, like voters, charged for their support. Martin Kelly justified such behavior in the case of franchises:

When men of wealth came to us for gifts which meant golden fortunes for themselves, does any fool suppose we didn’t ask for a modest “cut”? Of course we did. Was it not equitable and just?

Just as Huntington believed it “just and fair” to buy a vote in order “to have the right thing done,” so bosses and officeholders felt it “equitable and just” to charge for the services they could deliver.(46)

Closely contested elections and controversial legislative decisions rarely passed without someone—usually on the losing side—attributing the outcome to the purchase of votes. The claims appeared so frequently and gained such wide publicity that many assumed that the purchase of votes was inherent in the system. Some looked to the dominance of political parties as a major part of the problem and began efforts to break that power. The Australian ballot law marked the beginning of the attack on the power of parties, but the full-scale assault did not come for another two decades.

Some reformers sought to solve urban problems through the improvement of education, hoping to produce an educated and responsible electorate. Many hoped that the problems of the city could be solved simply by replacing corrupt officeholders with honest ones. Others hoped to induce respect and orderliness in the public through construction of imposing and inspiring civic edifices. Some condemned the saloon and brothel as agents of corruption in the body politic and demanded their abolition as essential to civic and social purity. One group of reformers sought changes in the structure of city government, finding the source of corruption in the weakness of the mayor, limits on the supervisors, and the consequent need to centralize decision making outside the formal process of city government. The new state constitution of 1879 had provided that San Francisco might draft a replacement for the Consolidation Act, and three proposals for new charters were placed before the voters, in 1880, 1883, and 1887. Buckley opposed these efforts, and voters defeated all three. Few reformers, however, addressed the central question posed by Henry George in 1880:

When, under institutions that proclaim equality, masses of men, whose ambitions and tastes are aroused only to be crucified, find it a hard, bitter, degrading struggle even to live, is it to be expected that the sight of other men rolling in their millions will not excite discontent?

His answer was equally disquieting:

The political equality from which we can not recede, and the social inequality to which we are tending, can not peacefully coexist.(47)

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 6 “Politics in the Expanding City, 1865-1893”