Introduction to the SOMA

Historical Essay

by Gayle S. Rubin

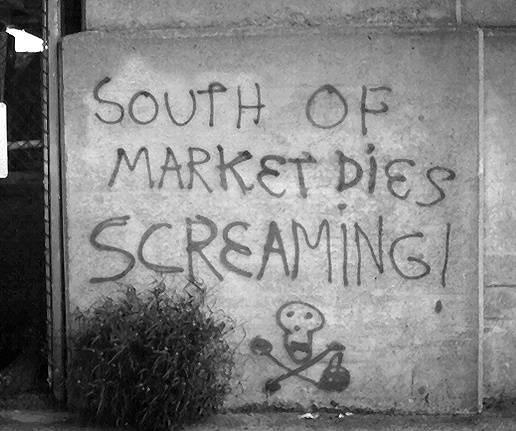

Graffiti in the SOMA: South of Market Dies Screaming!

Photo: Gayle Rubin

More than any other neighborhood in the city, South of Market is the part that contains the whole: the one matrix that subsumes unto itself every successive layer of urban identity in the history of the city. Here indeed is the anchor district of San Francisco: the site of all of its early institutional life: churches, orphanages, schools, unions, hotels, and public institutions. Here is the residential district of its most diverse population. . . . South of Market was an urban district containing the full formula of the city.

--Kevin Starr, South of Market and Bunker Hill, California History (Winter 1995-96).

Market Street is one of the primary corridors of San Francisco. It cuts a sharp diagonal across the city from the Ferry Building to the base of Twin Peaks. The trolley rails along Market Street have long marked a physical and psychological boundary (the Slot) between the area north of Market, where the local centers of political and commercial power are situated, and the predominantly poor and working-class area South of the Slot.

The South of Market was first settled during the Gold Rush: A tent city sheltering perhaps a thousand would-be gold miners, it was called Happy Valley for its sunshine, shelter from prevailing winds, scrub oaks, spring water, and carefree inhabitants. (Bloomfield 19956, 372) Much of the present neighborhood was then a marshy swamp or entirely under water. Like most of San Francisco's shoreline, the South of Market was largely manufactured through the liberal application of landfill. Most of the city's early industries were located here, including iron foundries, boiler works, machine shops, manufacturers of bullets and shot, breweries, and warehouses. The wharves South of Market were a focus for shipping and shipbuilding. The residential population worked in these industries or in other nearby commercial enterprises. (Bloomfield 1995-6, Averbach 1973)

Leveled by the 1906 earthquake and fire, the South of Market was quickly rebuilt, and became part of San Francisco's commercial downtown. The South of Market did not, however, match North of Market in uses. Here there were no major department stores, fashionable boutiques, banks, or except for the Palace, leading hotels. The owners did not anticipate such high-rent tenants and they built accordingly. (Bloomfield 1995-6, 387) While the postquake South of Market sheltered many working-class families, it was also an area with a high concentration of single working men and seasonal laborers. This had been the case since the Gold Rush days, when miners and field hands wintered in San Francisco, and seamen and transient workers stayed when they were between jobs or looking for work. (Averbach 1973)

Southerly along 9th Street at Howard, July 18, 1933.

Photo: [http:/www.sfmta.com/photo SFMTA Photo Archive U14123]

This pattern intensified after the 1906 earthquake and fire. Most of the labor force that rebuilt San Francisco lived in the South of Market and much of the housing constructed there after the quake consisted of residential hotels. The city's shipping industry continued to dominate the eastern portion close to the waterfront. Seamen and dockworkers lived nearby, and service businesses in the neighborhood catered to them. The headquarters of maritime unions were in the South of Market, and the area seethed with labor activism. (Issel & Cherney 1986, Bérubé forthcoming)

World War II brought new working populations. Averbach notes that:

South of Market emerged in 1950 with almost nine times the black population it had held before the war. . . . This recently arrived group was part of the great wartime migration of workers who followed numbers of Chicanos who had begun to move into South of Market in the early 1930s. . . . During the 1950s, the southwestern half of South of Market served as a reception area for a Filipino population of seasonal migratory workers. (Averbach 1973, 215)

While the ethnic composition of the transient poor changed, the general character of the neighborhood remained relatively stable until the 1950s. Then came the era of slum clearance and urban renewal.

excerpted from "The Miracle Mile, South of Market and Gay Male Leather 1962-1997" © 1997 by Gayle S. Rubin, in Reclaiming San Francisco: History, Politics, Culture (City Lights Books, 1998)