The Octopus and the Big Four

Historical Essay

by Ben Ratliff

May 9, 1869: Crowds celebrate completion of Transcontinental Railroad at Montgomery and Washington Streets.

In 1859, Theodore Judah convinced four relatively unknown merchants in Sacramento to invest in his proposed railroad to run from the gold mines through the treacherous Sierra foothills toward the eastern seaboard of America. At the time, the investment was a considerable gamble on something few people thought likely to pay off any time soon. The four investors--Leland Stanford, Collis P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins and Charles Crocker--had to wait a few years for the pay-off on their seed money for Central Pacific.

When the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, the four investors laughed all the way to the bank. They had effectively laid the groundwork to establish one of the most comprehensive and oppressive monopolies in American history. The four merchants eventually dubbed themselves The Big Four and their many-tentacled empire of railroads and freight lines was renamed Southern Pacific Railroad in 1884, although its detractors preferred to call it the Octopus.

In 1862, Congress approved the Pacific Railroad Act which awarded government contracts to two companies--Union Pacific and Central Pacific. The plan was for the two companies to build toward each other, from Omaha and Sacramento respectively, until they met. The federal government had a vested interest in the railroad and it generously subsidized the Central Pacific Railroad, aiming to get its slice of the Golden pie to help fund its war against the South. In addition, the Big Four created their own construction company and charged the United States inflated amounts to turn a healthy profit while they advanced their operations.

Unfortunately for the Union, the railroad wasn't complete until long after the Civil War had ended. On May 10, 1869, the fabled golden spike was driven into the final tie at Promontory, Utah and the United States eastern and western coasts were summarily linked. The illustrious golden spike can be viewed today at the Stanford University Art Museum.

The landscape of the Bay Area lent itself nicely to exploitation by the Big Four. With the completion of the transcontinental railroad, a new era of overland commerce in America had begun, linking the formerly isolated West Coast with the manufacturing-intensive East Coast. Central Pacific was the only company that had laid track going east. In addition, the Big Four started building railroads that linked the Bay Area with outlying communities that provided raw goods for San Francisco. The peninsula of San Francisco--insofar as it had no bridges to the mainland--was an island, for all purposes of trade with the east coast. Any such commerce necessarily happened vis-a-vis ships and ferries that ran across the Bay.

The Big Four eventually exploited this bottleneck by purchasing the majority of ferry and steamship lines that ran from the East Bay to San Francisco--the seat of commerce and wealth in California. By the early 1870s, they had established a de facto monopoly on California shipping by establishing control in San Francisco, leaving producers and retailers no option but to meet Southern Pacific Railroad's exorbitant costs or have their product rot in the warehouse.

As the name indicates, the Octopus was not popular with the general public. Although railroad advocates had hyped up the potential financial gains to be had from the railroad, its actual impact was resoundingly negative. In 1868, Henry George had written an editorial for the Overland Monthly predicting a recession for San Francisco once it became directly linked with the larger economy. He was proven correct. San Francisco suffered one of the worst depressions in its history when the railroad was completed. The Big Four, however, did not suffer, as manifested by the opulent mansions that began to sprout up on Nob Hill. Through corruption and force of momentum, Southern Pacific retained its monopoly on California commerce into the twentieth-century. Finally, in 1910, San Francisco elected a reform government that managed to break the stranglehold of the Big Four and a rival railroad began operating.

Leland Stanford (1824-1893)

Leland Stanford was one of those fabled souls that went West (young man) and made his fortune. In 1852, Leland came out to Sacramento to help his brothers run a thriving grocery business. After gaining control of the grocery, Stanford hit a lucky roll when one of his customers went belly up and paid off his debt to the grocery with gold mine stock. Shortly thereafter, the mine went bonanza and Stanford soon had a small fortune of half a million dollars.

In 1859, Stanford invested in the grand railroad scheme of Theodore Judah that was destined to make him a wealthy man. When his investment started reaping seemingly boundless returns, Stanford had a mansion built on Nob Hill in 1876. Until then, Rincon Hill had been the site of choice for the well-to-do in San Francisco because it was more accessible. After the first cable car was installed in 1873 (on Clay street), Nob Hill became the new hot spot for the moneyed class and Rincon Hill fell from prominence, destined to become a mere nub holding up the Bay Bridge. Leland Stanford was the first to lay out his spread on the hill, followed by his cronies at the Big Four club. The opulent Stanford mansion burned to the ground in the unremitting San Francisco fire of 1906. Today, the Stanford Court Hotel stands where the mansion was.

Stanford used his financial clout to the end of political power. In the nineteenth-century it was easier to buy a public office than it is today. Stanford was governor of California for two years during the Civil War. He became a U.S. senator two decades later by bribing state legislators to elect him. State senators were not elected by popular vote at that time.

Leland Stanford also built the now-famous Stanford University in honor of his only son, who died of typhoid in 1884. The university was located on his farm in Palo Alto. In spite of the astronomical wealth Stanford had earned, his university was almost forced to close in 1893 when Stanford died in debt. However, his wife Jane managed to keep it open.

Collis P. Huntington & Charles Crocker

Huntington and Crocker also followed Leland Stanford up Nob Hill and planted their own ostentatious mansions. Huntington, however, was in Washington most of the time, bribing high-level Congressmen to be favorable to the Southern Pacific in their legislation. Crocker built not one, but two, mansions on Nob Hill -- one for his son as a wedding present. He ran into a problem, however, when one stubborn German undertaker named Nicholas Yung would not sell his property to accommodate the Crocker spread. Crocker had been able to buy out everybody on Nob Hill save for this one gentleman.

Crocker, enraged, retaliated by building a 40-foot fence around the back of Yung's house, obliterating sunlight and Yungs nice view of San Francisco. The notorious spite fence became a rallying point for San Francisco citizenry as a symbol of big business oppression of the common man.

Mark Hopkins

Under goading from his wife, Mary, Mark Hopkins commissioned an excessively elaborate mansion to be built near the Stanford estate. Mary had a taste for the Gothic and ordered up a host of turrets, spires and other excessive ornamentation to be built. Unfortunately, Hopkins died before his fabulous mansion was completed and he never had a chance to enjoy it. Hopkins' mansion then became the Hopkins Institute of Art and then burned in the 1906 fire, along with the rest of the Big Four's mansions. Today, the Mark Hopkins hotel now occupies the site.

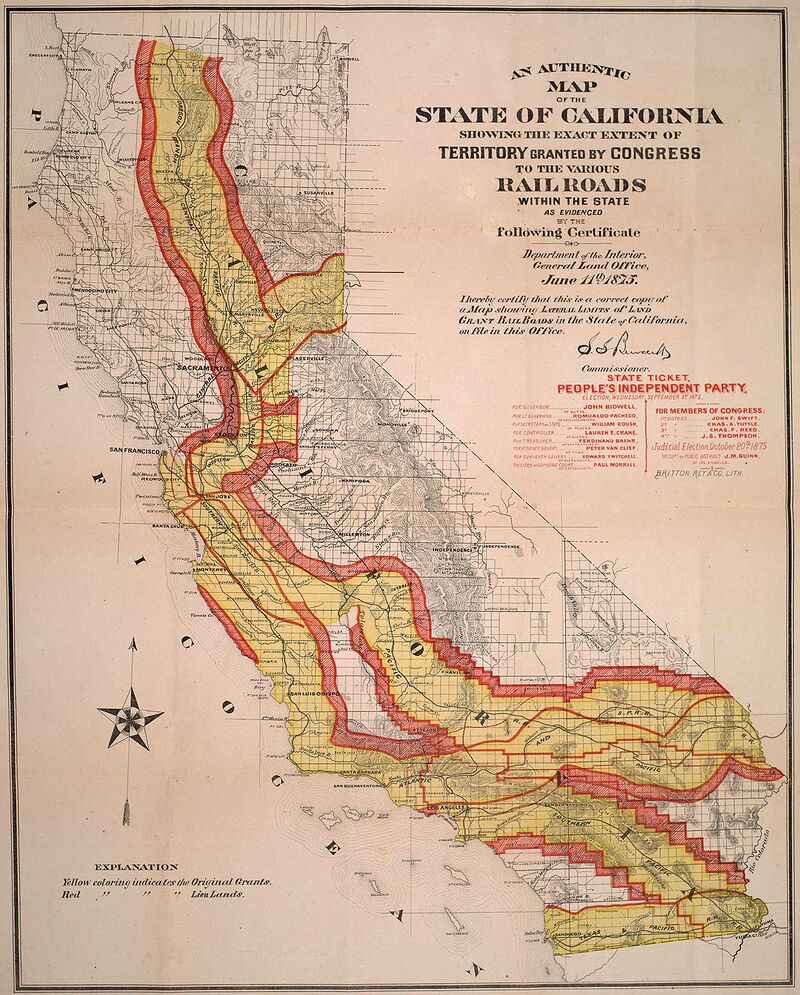

Dept. of Interior General Land Office map of railroad land grants in California, June 11, 1875.

Map: Online Archive of California