Valencia's Story

Historical Essay

by Brad Wieners, 1997

22nd and Valencia, 1944.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp27.50132

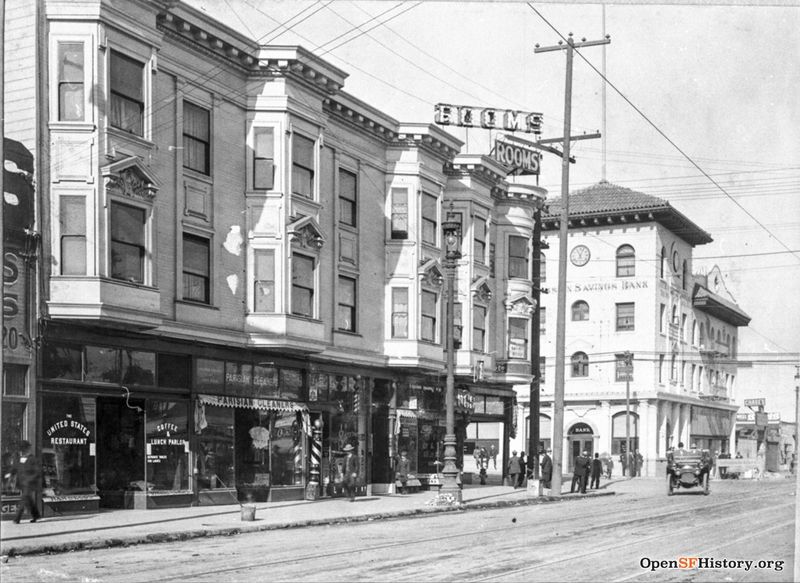

West side of Valencia Street at 16th, c. 1910.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp33.03313

Valencia Street takes its name, according to historian Louis K. Loewenstein, from either Jose Manuel Valencia or his son, Candelario Valencia. It's unclear from documents at the California Historical Society if Valencia Street pre-dates the formal naming of San Francisco, in 1847, but Valencia Street is at least 149 years old.

Jose Manuel Valencia traveled north with Juan Bautista de Anza's company from Sonora, Mexico in 1775, and when Anza returned to Mexico, it appears Valencia pressed on with a smaller group, led by Moraga, that established a post where the Presidio is today. That would put Valencia Senior in the region 60 years ahead of El Paraje de Yerba Buena, the predecessor to San Francisco.

From the beginning, Valencia Street featured an ethnically mixed population, evinced, among other things, by an 1866 court case, over a plot of land within what is now the Mission Dolores, between Paula and Candelario Valencia and John Cabot. In the late 1880s, 21st and Valencia sported one of the West's best nurseries, (according to the nursery itself), and many of the casualties in the 1906 quake were attributed to the collapse of the Valencia Hotel.

In the 20th century, if photographs don't lie, Valencia Street had already established the mix of residences and businesses it has today. Prints from the turn-of-century reveal storefronts, bars and elegant Victorians. More recently, in the late 1970s, Valencia earned a reputation as a place "where the women are." With the Women's Building, on 18th Street near Valencia, the Cafe Artemis, Amelia's, Esta Noche, and Old Wives' Tales, not to mention the transformation of 777 Valencia from a mortuary to the New College, Valencia had, by 1983, already gained notice as an "emerging bohemia." Under the headline, "The Women's District," Margot Patterson Doss of the Chronicle wrote that Valencia "looks like Lower Nowhere," yet "serves a mix that includes Mexican, Central American, South American, Native American, Caucasian, Black and other ethnic groups, as well as gay of both genders."

The Gantner-Maison-Demoergue Funeral Home at 777 Valencia Street in 1964 (later New College of California in the 1980s-1990s, now The Chapel nightclub and restaurant).

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Even as some of the establishments that identified Valencia as a gathering place for women closed over the last five years, (others like Good Vibrations, and Osento, it should be pointed out, have flourished since then), Valencia has emerged from bohemia to become a place, like Columbus Avenue in North Beach, where the entrés are. And, though picking a turning point for this latest phase is somewhat arbitrary, most of the merchants and residents I spoke to, (a few dozen over two months), think of two auspicious openings: Esperanto and Val 21. Both opened within the last 5 years.

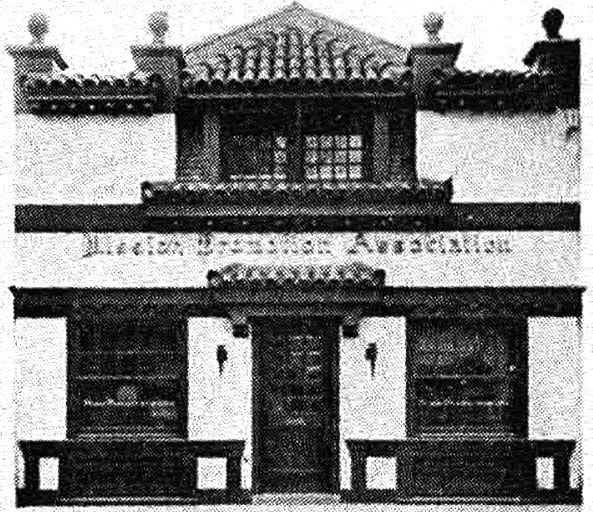

Taqueria La Cumbre, which claims to be the original inventor of the Mission burrito, is in the Spanish colonial revival structure that was the headquarters of the Mission Promotion Association in 1909 (an local business organization of mostly Irish members).

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Mission Promotion Association headquarters, 1909. Same building as Taqueria La Cumbre today.

Photo: courtesy Ocean Howell

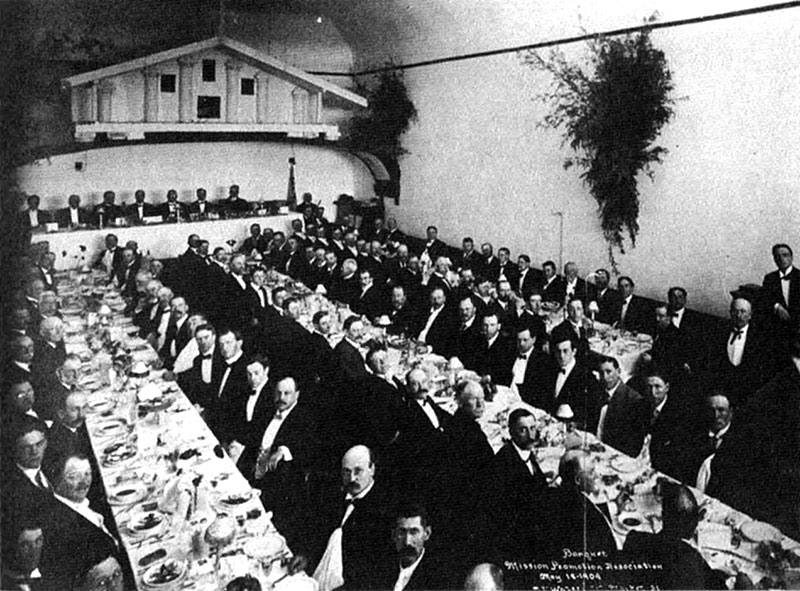

Gathering of local Irish businessmen in the Mission Promotion Association hall, 1909.

Photo: courtesy Ocean Howell

Lucca's Deli, much beloved landmark at 22nd and Valencia, seen here in 2019 before it closed for good in 2020.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Roxie Cinema on 16th near Valencia, one of the city's most stalwart small movie houses, has survived the videotape revolution!

Photo: Chris Carlsson