California Midwinter Fair of 1894: Women’s Work and Vice

Historical Essay

by Barbara Berglund

Two Gum Girls in front of the Walter Baker Cocoa Building at the Midwinter Fair, 1894.

Photo: Private collector, via OpenSFHistory.org, wnp15.145

While rugged, independent, white manhood was literally and symbolically displayed at the ’49 Mining Camp, women workers constituted a significant part of the overall spectacle presented at the Midwinter Fair. As writer Elisabeth Bates put it in an article for the Overland Monthly, “Two distinct streams of people flow side by side at the Fair, namely, those who go to spend money and those who go to earn it.”(50) Thousands of women in San Francisco faced unemployment and “destitute circumstances” during the five-year economic depression precipitated by the Panic of 1893. Nationally, this financial crisis devastated broad sectors of the economy and an unprecedented 15,252 American businesses went into receivership. By the winter of 1893, approximately 18 percent of the national workforce was without work while those who remained employed found their wages cut by an average of nearly 10 percent. The economic crisis hit the western United States especially hard. As eastern money receded, the already cash-starved banks of the debtor West collapsed. Of the national bank failures in 1893, only three institutions in the Northeast suspended operations while 115 banks went into receivership in the West. Of these, sixty-six were in the Pacific states and western territories. Since private charities and relief efforts largely ignored the plight of working women, many “suffered severely for food and clothing” during these years.(51) Within this context, many women hoped that employment at the Midwinter Fair would at least temporarily cure their economic troubles. The Examiner reported that “in every department” of the fair there was “the same story to tell.” There was “a constant stream of applicants for work” with “girls not over twenty-two” making up “four out of every ten applicants.” They seemed “to be pouring into the city from all over the coast” as well as “from the East.” This, according to the journalist, was “a terrible mistake” as the city was “overrun with women and girls looking for work.”(52)

Women working on "Cairo Street" in the Midwinter Fair, 1894.

Photo: Private collector, via OpenSFHistory.org, wnp15.147

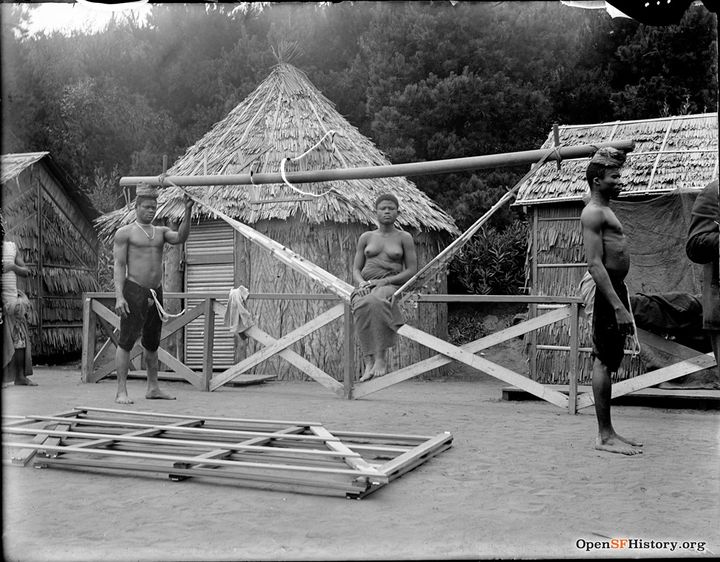

The lucky few who found jobs at the Midwinter Fair formed a workforce of women that spread all over the fairgrounds. Gum girls, dressed in blue uniforms with scandalously short skirts, traversed the grounds—smiling, singing, and selling chewing gum. Exposition cash-girls collected the admission fees for various concessions and young women staffed booths in the fair’s five main buildings. Other women found employment in the fair management’s system of “paternal espionage” in which “real nice girls, with a knowledge of business methods” were “sent among the different concessions to keep tabs on the cash taken in.” Almost all the exhibits of foreign nations and people of color employed women. Native American, Hawaiian, Samoan, and Dahomean women staffed living dioramas. At the Japanese Tea Garden, “Japanese maidens in their kimonos” served visitors “tea and sweetmeats.” At the Vienna Prater, waiter girls served liquor and Austrian dishes. In the German Village, visitors found “a concert hall, a dancing hall, a restaurant, and, of course, Culmbacher and Wurzburger and other ‘braus’ and proper German girls to curtsy and serve it.” At the Hungarian Csarda, one encountered “other girls and other beer and other things to eat,” giving the impressions that all Austro-Hungary was “a vast eating place with feminine and drinkable incidents and an occasional park to give you exercise when you want to change your beer.” Women of Mexican as well as Euro-American descent worked as dancers at the ’49 Mining Camp while the Oriental Village maintained a troupe of young women as muscle-dancing Turkish Dancers. At the Tamale Cottage, the Official Catalogue informed its readers that “handsome, dark-eyed senoritas” could “be seen busily engaged in the manufacture of the delicious tamale” while “other equally charming beauties” worked “as serving maids.”(53)

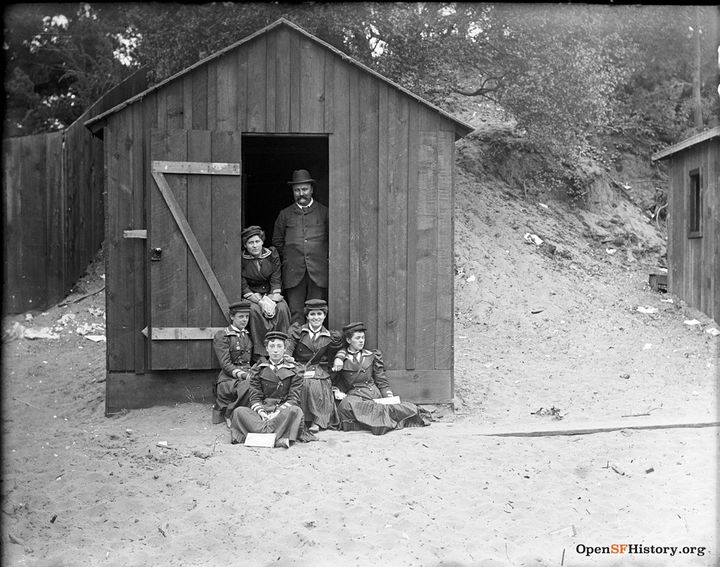

Dahomey Villagers at Midwinter Fair, 1894.

Photo: Private collector, via OpenSFHistory.org, wnp15.131

Since the Midwinter Fair brought men and women together in novel, sometimes promiscuous ways, it—like the promenades of the Mechanics’ Institute’s fairs—provided an arena in which emerging gender identities could be expressed and critiqued. Working women at the fair became vehicles through which various observers registered anxieties about women’s more public roles and the fair’s working women experienced for themselves both the perils and the pleasures of increased leisure time and new work-based peer groups. Nationally, during the final quarter of the nineteenth century, increasing numbers of middle-class women pushed into the public sphere and against the constraints of Victorian culture’s dominant gender ideology that prescribed piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity. At the same time, many young working-class women shifted from working at various types of piece-work in their own homes, in domestic service in other people’s homes, or in small, paternalistic factories to working in the more anonymous settings of large factories, offices, and retail stores. With a little money in their pockets in good economic times and new places to go for fun, some of these young women began to rebel against the gender ideologies of parents and society and to explore new identities and forms of sexual expression in part made possible by new, unchaperoned commercial spaces for heterosocial encounters. The turn of a significant proportion of middle-class men away from effete Victorian culture and their embrace of a new rugged masculinity—as seen in the ’49 Mining Camp—was, in part, a response to anxiety aroused by women’s more public identities.(54)

All women who worked at the fair were essentially on display and available for appraisal, fantasy, and flirtation in the exposition’s climate of promiscuous mingling. As some of the stories that circulated around the fair’s gum girls reveal, this public, sexualized persona treaded a thin line between representing a welcome freedom from social constraints and confirming a subordinate position vis-à-vis men for the women involved. That the fair was a place where men could gaze upon an international array of women was made clear from numerous articles that related the pleasant sights that other men had seen. Some of these even provided details of heterosocial encounters that perhaps their readers could hope for as well. An article published in the Examiner titled “Flirtations at the Fair: How Love Is Made and Unmade at Sunset City” advised male fair-goers that “for really enjoyable and promiscuous flirtations . . . the gum girls, so called, are better equipped than any other class of individuals as regards their duties, their skirts and their generally genial disposition.” Not only could they roam the fairgrounds at will but “they may stop and talk pretty things with anybody under the pretext of vending gum.”(55)

Sometimes flirtations were a source of heterosocial fun for the gum girls and their patrons. But with this kind of fun also came a certain amount of sexual danger. Giving one possible explanation for why they traveled in pairs, one gum girl said, “You see, there are two of us, and if you get badly gone on me and I don’t want you to get too affectionate, Sally here stays close around all the time, and you don’t have a show to tell a girl how much you love her or any of that sort of nonsense. But then, of course, if I give her a wink she understands and goes off to sell some gum.” Sometimes, however, flirtations were anything but fun. One gum girl, Miss Violet Eilids, warded off the advances of a souvenir-machine man by deploying “her fists in a scientific manner.” After he “sought to toy familiarly with Miss Eilids’s necktie” while she was trying to sell him some gum, she punched him squarely in the nose, leaving him with “a barked proboscis.” The paper that covered the story reported that, “She as well as the rest of the girls have to stand a great deal of guying from a class of men who think that because a girl peddles chewing gum she can endure all sorts of nonsense.” Violet had learned boxing from her brother and after seeing how well it served her, the rest of the gum girls were “thinking of taking an immediate course in the manly art as a means of self-protection.”(56)

Home of the Gum Girls in the Midwinter Fair.

Photo: Private collector, via OpenSFHistory.org, wnp15.146

Although ostensibly from Algeria, Morocco, Persia, and Egypt, the so-called Turkish Dancing Girls at the Midwinter Fair’s Oriental Village presented even more of a sexually charged sensation than the gum girls. While undoubtedly alluring in their own right, the press definitely had a hand in the construction of the dancers’ highly sexualized image that was based, in part, on notions of the heightened sensual appetites and sexual availability of colonized women of color that were part and parcel of Orientalist thinking. The Examiner described “the Oriental dames and damsels” as a “desperate class of flirts . . . who cast reciprocally amorous glances through ebony lashes” and make “callow youths feel the fire of those langorous looks and brag to one another about their conquests.” These dancers had performed at the Chicago Fair to rave reviews. There they faced fewer questions about the morality of their dancing than in San Francisco where they were besieged by the Society for the Suppression of Vice as early as mid-December 1893. On January 4, 1894, the Examiner reported that “Catherina Dhaved and Marietta, the two dark-eyed daughters of Turkey who were compelled to desist from giving public dancing performances on Market street a few weeks ago by the Society for the Suppression of Vice, visited the officers of the society yesterday.”(57)

Secretary Kane, who had witnessed the women’s dancing, had no doubt of its “rank immorality.” Nevertheless, the dancers had to endure a wait of several days before the society’s directors could manage to convene for a viewing of their dances to determine if they were in fact immoral. The “sample dances” were performed in one of the rooms occupied by the women in the Ahlborn House on Grant Avenue. The “all-male audience,” according to the Examiner, “was small, compact but interested from the start.” It consisted of the five directors and Secretary Kane of the Society for the Suppression of Vice, two members of the Society for the Prevention of the Cruelty to Children and Animals, and Captain Holland of the Police Department. “We can judge better the morality or immorality of the dance by seeing it all, I think,” said Director Morris, with no recognition that such private viewings might raise questions about the prurient interests of the audience. “The Directors,” reported the Examiner, “leaned forward and watched the excited dancer with scrupulous interest. Unconscious of them the beautiful Catherina pirouetted in a dizzy circle, and falling to her knees bent far backwards half a dozen times. Her whole form quivered with the excitement of the moment.” Director Goodkind concluded that the dance was “very picturesque but . . . hardly the thing for ladies and children to see,” leaving unremarked upon the effect of such a performance on male audience members or the fact that such a spectacle may have been designed to be more appealing to male viewers to begin with.(58)

An earnest desire to rid the city of indecency—which included safeguarding the ordered environment created by Midwinter Fair organizers and cracking down on the Barbary Coast—motivated the Society for the Suppression of Vice. For the Turkish dancers, however, the Society’s decree that deemed their dances to be beyond the bounds of respectability and prohibited their performance meant a disruption in their capacity to earn a living. “In Chicago everybody liked us,” Catherina Dhaved told the Examiner, “We made a big hit in the Midway Plaisance; thirty-five an’ forty dollar week; plenty to eat, plenty sleep, plenty everything—plenty money.” Since coming to San Francisco, however, the girls had experienced “perilous times.” By early January they had earned about $1,000 in the employ of two different leisure entrepreneurs in the weeks before the fair opened but had not “received a cent of it.” “First an Armenian man hired us,” Catherina continued, “Twenty-five dollars a week, on Market street. We work one, two three weeks, no money. Then an American man, Crosby, hired us. We work one, two, or three weeks more, no money. We owe plenty money at the hotel, and now we cannot dance and cannot pay what we owe.” During the time they waited for the directors to convene in early January, the women lived on “short rations.” When the dancers finally performed for the Society for the Suppression of Vice, the proprietor of their hotel was also present as “an interested witness.” According to the Examiner, “He told the Directors that the girls owed him about $100 for back board and he did not propose to keep them any longer unless he was assured that they would be allowed to dance and make some money.”(59)

Several days later after the “sample dances” at the Alhorn Hotel, on January 7, 1894, the Society for the Suppression of Vice paid a visit to the Turkish Dancing Girls performing at the Midwinter Fair. Although the fair did not officially open until later in the month, by early January so many concessions were open that thousands of people were paying to pass within its gates. Once again Secretary Kane expressed displeasure at what he saw, especially since “the dancers had received strict instructions to tone down their performance to suit Western audiences.” A “sample” of the entire dance was again presented that same day for “the edification of the secretary.” To guard against errors in either leniency or severity, two other agents of the society accompanied Secretary Kane as well as “a newspaperman or two, a company of Turks, and a few chosen friends.” The Examiner reported Kane’s findings on January 10, “In the muscular contortions of the majority of the ladies he found nothing to object to seriously; but in the closing measures of the danse du ventre, as rendered by the dusky Egyptian Hamede, he found grievous cause for complaint.” Kane remained steadfast in his judgment even though the press cited the chief of the Midwinter Fair police as one among many admirers of the dance who did not object to it. The Examiner’s reporter captured the way that Hamede’s gyrations left Kane unnerved to the point of scrambling for words to describe what he had seen. “The muscular dances and the spinning exercises of the majority of the ladies can go on,” he was reported as saying, “but the -er-er-er the eccentric convolutions of the little brown lady must be curtailed.”(60)

Three months later, on April 9, 1894, the Turkish Dancing Girls had their day in court. As the Call reported, “Under the glare of the gaslights and in the suffocating heat of Judge Conlan’s courtroom the muscle-dancers of the Cairo village last night illustrated their peculiar dance for the benefit of the jury impaneled Friday last.” Secretary Kane’s testimony about the dance demonstrated that he “had studied it pretty thoroughly” and the description provided by Frank D. Gibson, a hardware clerk, likewise “showed keen powers of observation and perception, and that he had the dance down finer than even Secretary Kane.” Nevertheless, despite the fact that the dance had been made familiar to officials through two sample performances as well as shows on Market Street and at the fair, the dancers’ attorney requested that one of the dancers, Belle Baya, “give a representation of the dance.” She agreed to perform to the packed courtroom despite the fact that she was not outfitted in her dancing costume but in a “lilac silk dress, lace fichu and white straw hat with green and white ostrich feathers.” As the Call described, “Belle Baya followed in her dance, taking a silk handkerchief in each hand and the castanets on her fingers. The solitary fiddler mangled ‘La Paloma’ with frightful barbarity as an accompaniment. As the handsome Baya went through her dance the auditors went wild with excitement, and a clapping of hands was sternly rebuked by the court.” Order was restored in the court in the wake of Belle Baya’s dancing and proceedings in the dancers’ case came to a close soon after. Her performance had apparently satisfied the jury that there was truly nothing immoral in her dance. “The case was submitted without argument,” reported the Call, “and the jury retired at seven minutes past 11, returning five minutes later with a verdict of ‘not guilty.’ ” The jury, it seems, had a much different opinion than the Society of what constituted the kind of indecency that would mar the city’s image or detract from the glory of the fair.(61)

The Society for the Suppression of Vice’s policing—combined with the dishonesty of a couple of leisure entrepreneurs—was more successful in impeding the Turkish dancers’ ability to earn a living than in protecting them or their audiences from danger or immorality. Clearly, however, both the Turkish dancers and the gum girls were vulnerable to various forms of harassment as women working in the world of commercialized leisure. In July, the society turned its attention to another Midwinter Fair scandal that involved a woman worker who was so egregiously exploited by her male employers that she was actually in need of their efforts. On July 9, the Examiner reported that “the indecency of the danse du ventre and the grossness of the hula-hula were eclipsed last evening by an exhibition at the close of the Midwinter Fair which it is not permitted in the columns of a daily newspaper to describe further than by saying that the dancer was a nude woman.”(62)

More than five hundred men had witnessed two such performances at Alexander Badlam’s Aquarium on the Midway. The first evening the admission price was set at twenty-five cents “but there wasn’t room in the Badlam building for the crowd that was willing to pay that price.” As a result, the price on the second night was doubled “but the four-bit rate made little difference in the patronage.” Spielers on the Midway had openly announced the upcoming events and apparently fair officials not only knew about the performances, but a number of them, including Colonel T. P. Robinson, the director of amusements, were in attendance. In fact, at the performances, “every class was represented. The majority of those on the benches were well-dressed attorneys, merchants and clerks.” Also present were “concessionaires, sports, hoodlums, and men about town.” While the press reported that the “room was dirty and the atmosphere stifling,” the arena was also strategically equipped with an emergency door and a number of portholes that allowed for all but a few of the men present to escape arrest when the show was raided.(63)

Moreover, the Examiner’s account of Jennie Johnson’s dance and her subsequent arrest suggests that she was not operating under her own free will but was coerced by the manager of the event, Al Morris. “The sound of a violin drew attention . . . to the curtain which at the same moment was pulled aside revealing a woman seated in a chair enveloped in a dark cloak,” the newspaper explained. “At the sound of the music she sprang to her feet revealing herself perfectly nude. Her head and face were veiled in a black scarf. She thus displayed herself for a few moments. Suddenly the sound of the violin ceased and the ‘dancer’ sank into her chair.” As this account suggested and the press later confirmed, Jennie Johnson was not a professional dancer. Her performance did not even involve anything that could really be considered dancing. That she veiled her head and face with a dark scarf suggests she was ashamed enough of what she was doing that she did not want to be recognized. It is likely that she was also fearful of the arrest that might follow if she revealed her identity.(64)

Soon after Jennie Johnson returned to her chair, she was arrested by an officer of the Society for the Suppression of Vice who “sprang upon the stage.” Although initially quite calm, soon, amid a flood of tears, she exclaimed, “I was forced into it. The man said I would be arrested if I did not give this dance.” Apparently, the manager of the show, Al Morris, had convinced Jennie Johnson that if she did not perform she would be arrested for breach of contract. He had also “made her drink a liquor” before her performance. Morris also had refused to be specific about how much he would pay her, promising only “to make it all right with her” after she “danced.” Jennie Johnson was about twenty years old and a resident of the Tenderloin district, one of San Francisco’s rougher and poorer neighborhoods. It is possible that she was one of the many working-class and poor women facing exceptionally dire straits as a result of the economic depression. In such circumstances, the threat of a lawsuit might have been especially terrifying to her and maybe whatever Morris was willing to pay her was better than nothing. It is also possible than Jennie Johnson worked as a prostitute and perhaps she felt that displaying herself nude was a better job than having sex for money. Whatever the answers to these questions might have been, Jennie Johnson confessed that she had been “duped by an enterprising spieler—that his promise was as deceptive as any fake on the Midway.”(65)

Notes

50. Bates, “Some Breadwinners at the Fair,” 374–384.

51. These figures on the Panic of 1893 are from the Utah History Encyclopedia located at: http://eddy.media.utah.edu/medsol/UCME/p/PANIC1893.html; Chronicle, January 10, 1894.

52. Examiner, January 6, 1894 and Call, July 13, 1893.

53. Chandler and Nathan, Fantastic Fair, 21, briefly discuss the gum girls; Examiner, February 11, 1894; Examiner, January 28, 1894; Official Catalogue of the California Midwinter International Exposition, npn. Dahomean women were from Dahomey, Africa.

54. For discussion of places of amusement as sites of gender politics see: Kathy Peiss, Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure in Turn-of-the-Century New York (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986); Elaine Tyler May, Great Expectations: Marriage and Divorce in Post-Victorian America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980); and John Kasson, Amusing the Million: Coney Island at the Turn-of-the-Century (New York: Hill and Wang, 1978).

55. Examiner, February 11, 1894. See also Examiner, January 28, 1894.

56. Examiner, February 11, 1894; Chronicle, May 6, 1894. The women who worked at the Tamale Cottage were also said to “flirt coquettishly with the patrons who sit around the tables eating tamales,” Official Catalogue of the California Midwinter International Exposition, npn. That the climate of heterosociability could proved dangerous was attested to by the results of a contest, run by The Irish Whiskey, in which one of the “young ladies employed in various capacities in the Agriculture building” was judged the “Most Popular Lady, Midwinter Fair, ’94,” Chronicle, June 21, 1894. Mrs. Bessie Findlay, the winner, was subsequently shot and wounded by her abusive, idle, and alcoholic husband in a fit of jealousy prompted by her victory as well as the fact that she and a girlfriend were escorted home by two boys they had met in the Manufactures Building, Examiner, July 9, 1894.

57. Examiner, February 11, 1894; Chronicle, November 29, 1893; and Examiner, January 4, 1894.

58. Examiner, January 4, 1894 and Examiner, January 6, 1894. See also Nathan and Chandler, Fantastic Fair, 22–23.

59. Examiner, January 4 and January 6, 1894.

60. Chronicle, January 8, 1894, and Examiner, January 10, 1894. The danse du ventre is also known as belly dancing.

61. Call, April 10, 1894.

62. Examiner, July 9, 1894. See also Chandler and Nathan, Fantastic Fair, 63–65.

63. Examiner, July 9 and July 10, 1894.

64. Examiner, July 9 and 10, 1894.

65. Examiner, July 9 and 10, 1894. On July 10, 1894, the Examiner reported that there may have been a different dancer for the first performance and thus cast doubt on the credibility of Jennie Johnson’s assertions that “Al Morris, the spieler who had charge of the exhibition, threatened to have her arrested for taking part in the dance on Saturday night.” Although the press suggested that Miss Johnson may have been trying to “evade some portion of the responsibility resting upon her,” the evidence still points to coercion. This was not an example of an empowered sex worker.

Originally published in chapter 5 “Imagining the City: The California Midwinter International Exposition” in Making San Francisco American: Cultural Frontiers in the Urban West, 1846-1906 by Barbara Berglund (University Press of Kansas: Lawrence KS 2007)