45 Westpoint: A World of Possibilities

"I was there..."

- "Foundsf.org is republishing a series of "Tales of Toil" that appeared in Processed World magazine between 1981 and 2004. As first-hand accounts of what it was like working at various jobs during those years, these accounts provide a unique view into an aspect of labor history rarely archived, or shared.

by James Tracy

—from Processed World #2.005, published in Winter, 2005.

Photo: Joseph Smooke

Thanksgiving Morning 2003. At the intersection of 30th and Mission an odd assortment of humanity gathered—even by San Franciscan standards. Homeless families, most with strollers in tow, cautiously mingled with trade union activists. College students tried out their Spanish on Latino day laborers. Street punks, checked out the non-profit workers with a sneer that acknowledged “I’ll probably be you one day.” The crowd of about 140 had diversity written all over it—elderly and young, and enough ethnicity to make even the most jaded observer speak about Rainbow Coalitions as if the idea was just invented five minutes ago.

Protest signs handed out casually read “Let Us In!” below a cartoon of a global village angry mob. The mood remained mellow, maybe strangely so for a group of people who, in an hour’s time would be participating in an illegal takeover of vacant housing; one unit among thousands owned by the San Francisco Housing Authority—the often troubled agency that is charged with providing homes for the city’s most impoverished.

Announcements are made: the bus chartered to bring the protesters to the secret takeover site is late, but will arrive shortly. The driver of the bus had been reached by cell phone and reported a hangover from which he’d just woken up. He would be stopping for a strong cup of coffee. Even on Thanksgiving Day, there was more than one protest going on in San Francisco. A couple of hundred feet away, United Food and Commercial Workers members picketed Safeway in the ongoing battle over the company’s attempts to do away with healthcare benefits. A delegation went over to wish the unionists well as one nervous housing protester tried to conceal the Safeway logo on her fresh cup of coffee.

The press showed up early to search for a spokesperson, played today by Carrie Goodspeed, a twenty-four-year-old community organizer with Family Rights and Dignity (FRD), part of the Coalition On Homelessness. She’s nervous at first but then relaxes. “The Authority owns over one thousand units of vacant housing that could be used to house families. We will risk arrest to make this point.”

“Is this the right thing to do?” blurted one reporter. There’s silence and an expression on Godspeed’s face of someone with second thoughts. Suddenly that expression disappears.

“Definitely. It’s the right thing to do.”

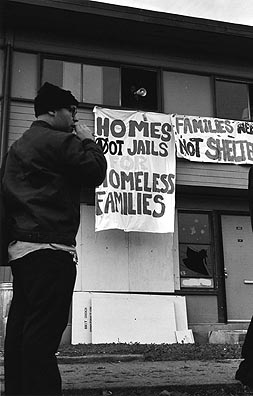

TAKEOVER! The caravan consisting of five autos, some bikes and the long-awaited bus arrived at the tip of the West Point Housing Development. Banners in the windows proclaim: “HOMES NOT JAILS FOR HOMELESS FAMILIES,” and “THESE UNITS SIT VACANT WHILE FAMILIES SLEEP ON THE STREETS.” The dwelling was opened up the night before by a team of members of FRD, Homes Not Jails (HNJ), and other assorted individuals. Some were there to pressure the SFHA into rehabilitating the vacant units and have a very politically correct Thanksgiving. Homeless people added another thoroughly practical aspect: “If I get busted, I sleep inside. If I don’t, I sleep inside,” one person remarked.

A speakout commenced in front of the building. Camila Watson, a resident of the development took the microphone. Watson is one of the reasons this action landed here—due to her outreach most of the neighbors are reasonably supportive.

When Watson was homeless, she turned for help to Bianca Henry of FRD, one of the women occupying the apartment. Watson’s name had “disappeared” from the SFHA’s waiting list. Extremely aggressive advocacy on Henry’s part, coupled with a clever media event the previous year, had helped the agency to “find” Watson and offer her a place to live.

“I used to come by here and think ‘Why can’t I live in apartment 41, or 45, or 47. Give me paint and a hammer and I’ll fix it up.” With housing, other good things have come to pass. Watson now holds down a job, and is doing well at City College. The experience left her determined to fight for those still stuck in the shelter system.

Photo: Joseph Smooke

“They say these units are vacant because people don’t want to live here. I haven’t met a mother yet that wouldn’t move here over the streets and the shelter.”

Another woman told a story of how her homelessness began the day the government demolished the public housing development she lived in, and reneged on promises for replacement housing for all tenants. One resident remarked how she feared taking homeless family members into her home, since her contract with the SFHA made that act of compassion an evictable offense. A young poet named Puff spoke in a style that was equal parts poetry slam, evangelical and comical. By the end of her microphone time she managed to connect homelessness, minimum-wage work, consumerism, police abuse, war and genocide. From someone with less passion and less street experience, it might have been indulgent. From Puff, it was a clear-eyed ghetto manifesto, and a call to arms.

The San Francisco Labor Chorus rallied the group in rousing renditions of post-revolutionary holiday favorites such as “Budget La-La-Land,” stretched to fit “Winter Wonderland,” and “Share the Dough,” set to the tune of “Let It Snow”. At first the very white group of trade unionists seemed a little out of place in the projects.

As many neighbors stopped by, a trio of young men came down the hill.

“Is that where the homeless people are going to live?” the tallest one asked.

“We hope so!” yelled Bianca Henry from the second floor window.

“How many rooms?”

“Three!” Henry replied.

The youngest looking of the three flashed a smile gleeming with gold caps “Happy Thanksgiving, yo!” as the trio continued down the hill.

The San Francisco Housing Authority and Hope VI

Life as San Francisco’s largest landlord and last line of defense against homelessness has never been easy. Born in 1940, the agency initially housed returning servicemen and their families. Over the years, it has grown to operate over 6,575 units of housing and administer another 10,000 units in conjunction with other providers.

In the 1980s then-Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Jack Kemp announced the creation of the Housing Opportunities For People Everywhere (HOPE) program that would tear down public housing and rebuild it. HOPE was intended to get the feds out of housing provision by transferring ownership to resident cooperatives. President Clinton took most of the hope out of the HOPE program (now called HOPE VI) when requirements for resident participation, return, and unit replacement were stricken from the federal record.

In San Francisco the HOPE VI program produced very mixed results. When it worked, it worked because tenant organizations forced it to work. Some developments lost units and the agency’s own numbers show that not every former tenant made it back to their former neighborhood. Many residents, some who lived through the “urban removal,” of the 1960s saw the demolition as one more attempt to kick Blacks out of town. It was widely believed that then Executive Director Ronnie Davis gave free reign to his staff to evict outspoken tenants, forge documents, and take bribes. Davis was never convicted of any wrongdoing while in San Francisco, but was convicted of embezzling from his former job—the Cayahuga Housing Authority in Cleveland, Ohio.

Today, the SFHA is led by Gregg Fortner, who is regarded by most as honest, if a bit inaccessible. Continued federal funding cuts have kept vacated units vacant—about 905 vacant units or 16%, total. To meet the deficit in operating costs, the agency requested proposals from both for-profit and nonprofit developers to redevelop eighteen properties—again raising the specter of displacement—dubbed “The Plan” by activists and residents.

This Town is Headed for a Ghost Town?

Ted Gullicksen, a co-founder of HNJ, knows how to use a bullhorn. Speaking from the broken window he invites the press and anyone else to check out the apartment. “It won’t take thousands of dollars to fix it up.”

Gullicksen, a working-class Bostonian helped to create HNJ to add a direct action complement to the San Francisco Tenants Union, which he directs. HNJ helps several “survival squats” (buildings seized for shelter not protest) in San Francisco. 45 Westpoint is a “political squat” used to protest the housing crisis, popularize demands, and generally raise a ruckus.

This ruckus is usually raised on major holidays, especially the very cold ones. San Francisco’s press is usually quick to broadcast sensationalistic stories about homeless people using drugs or having mental health episodes in public places. Such “journalism” has played a major role in mustering public support for punitive anti-homeless legislation.

On takeover days, the camera is forced to observe pictures of homeless people at their most powerful, not at their most vulnerable. Images of poor people and their allies repairing broken apartments replace one-dimensional images of addiction. HNJ specializes in the strategic use of a slow news day. Throughout the day facts, figures and theories on homelessness are thrown about, yet one message remains constant: “Nothing about us, without us.”

What about the former residents of 45 Westpoint? What happened to them and who were they? The house holds a few clues. Stickers on the upstairs bedroom door read “Audrina loves Biz.” Judging from the demographic of the development, they were likely Black or Samoan. Large plastic “Little Tykes” toys left behind suggest a child, probably two. A sewing machine, a conch shell and a broken entertainment center might be what’s left of a ruined family, but who knows?

What caused their exit? Maybe the family left in response to the gang turf wars that periodically erupt on the hill. They may have been recipients of the federal “One Strike Eviction,” Clinton’s Orwellian gift to public housing residents. “One Strike” passed in 1996, allowing eviction on hearsay for crimes committed by an acquaintance. Grandparents have been evicted for alleged crimes of grandchildren. A woman in Texas lost her home after calling the police to end a domestic violence incident in her unit.

Beyond “Services”

Bianca Henry surveys the Thanksgiving rebellion with pride, a grin playing at her lips. This is the first time she has ever committed an act of non-violent direct action. For someone who was raised in the projects and knows first-hand the over-reaching arm of the law, the fact that she is purposely risking arrest for the cause is a small, but dramatic personal revolution.

Henry’s pride in her work as an organizer is evident throughout. The takeover is part of an ongoing campaign to force the SFHA to house and respect families. Together with other parents, she has done one of the hardest things a community organizer can do: inspire poor people to move beyond “Case Management,” and “Services,” and take things to the next level: collective action, risky, scary, but potentially wonderful.

By design, the action is separated into two zones: the Arrest Zone (inside the house) and the Safe Zone (on the grass outside). It assumes a social contract with the police to respect Arrest and Safe zones. Henry knows first-hand that even minor brushes with the law can bring the wrath of the C.P.S., I.N.S., P.O.s and PDs and various other Big Brother-like institutions adept at tearing families apart.

Henry knows that if you want to get anything done, you can’t just wait for the next election. She might have been a Panther in the 1960s but there’s a pragmatic streak in her as well. She can effortlessly rattle off obscure public policy points and arcane aspects of the Code of Federal Regulations as they pertain to housing poor people.

Starr Smith is Bianca’s co-organizer. A single mom who came to work with FRD when she was still homeless, she’s on the outside fielding questions and dealing with the dozens of unforeseen snafus cropping up by the minute. They make an interesting team. Henry grew up in the thick of gangs and her neighborhood was devastated by the crack cocaine industry. She exemplifies the Tupac generation of young people who grew up in the era where every reform won during previous upheavals was being stripped away. Smith came of age following the Grateful Dead in the final days of Jerry Garcia. Both faced down long-prison sentences and have built the FRD’s housing campaign from scratch. In many ways the eclectic crowd is a reflection of this partnership.

Later in the afternoon one neighbor the group forgot to outreach to is steaming pissed—the President of the Tenants Association. She confers with Jim Williams, Head of Security of the SFHA. He in turn, asks Jennifer Freidenbach of the Coalition On Homelessness, to please call the agency when the protest is over.

“We’re not leaving, we’re moving more people in,” Freidenbach answers.

“Yeah right.” Williams retorted.

“Really.”

“Well…Why don’t we have our legal people call yours?”

Within the next 24 hours, the San Francisco Police Department had indeed cleared 45 Westpoint and the other units that had been reclaimed. This “Autonomous Zone” was finished, but the world of possibilities opened through good old fashioned mutual aid and a crowbar remained.

Rebuilding the Left One Block at a Time

“More often than not, reliance on voting in periodic elections has sidetracked them from the more powerful weapons of direct action. By engaging in the continuous struggle for justice and human welfare, workers will gain a realistic political education and cast the only ballot worth casting—the daily ballot for freedom for all.” —Bayard Rustin, New South…Old Politics

After the 1999 anti-WTO protests in Seattle, Elizabeth Betita Martinez, wrote an influential essay entitled “Where Was the Color in Seattle?” Unfortunately, one never needs to ask that question about prisons, slum housing, and homeless shelters. These are some of the most integrated institutions in the United States. Nevertheless, the loosely dubbed “Global Justice Movement” and those actually at the receiving end of global injustice are usually separated by vast cultural, political, and economic spaces.

For a day or so in San Francisco, this wasn’t the case.

In September 2003, the U.S. Department of Labor reported that over 34 million people lived in poverty inside the United States. This statistic should have annihilated propaganda that the cause of poverty is personal pathology. In a more honest world, factors such as a shift towards a low-wage service sector, welfare reform and out-of-control military spending would replace such distractions as marital status and personality in discussions of homelessness.

It could be a very good time for economic justice organizing in this country. Yet, as elections near, actions such as housing takeovers remain isolated by the liberal Left—marginalized by the urgency to “Elect Anyone But Bush.”

The women of Family Rights and Dignity and the squatters of Homes Not Jails aren’t waiting for the next election. They embody a spirit of past movements, such as the Unemployed Workers’ of the 1930s, which is rooted in the everyday needs of community members. They build direct democracy with crowbars as their ballots and vacant housing as their ballot boxes. Election strategies might occasionally produce short-term good—but survival politics outside of the formal legislative system are better at producing organizers from the ground-up. That builds movements without illusions—ready to rumble no matter a Bush or Kerry victory.

As an action initiated mostly by working-class women of color it also shows alliances can be built between America’s different dissident factions. It begins with supporting self-organized actions such as this and respecting the fact the communities who find themselves under the boot of poverty need people to have their back—not to act as spokespeople for their cause. Despite gentrification spasms, the city functions in a way similar to factories of old: a place where people of disparate backgrounds can meet, find common grievances and hopefully common collective action.

P.S. 45 Westpoint was made available to homeless families in late February 2004.