Lew Welch—A Journal of Remembrance

Historical Essay

by Stephen Vincent, January 15, 1972

Lew Welch and Allen Ginsberg outside City Lights Bookstore, San Francisco, October 30, 1963, (the day of the Madame Nhu protest).

Photo: © John Doss

March 1, 1971

Dear Lew,

I’m in the beginning of teaching a course at the Art Institute that I’m calling BAY AREA ART & POETRY since WWII. (I come out of the poetry end of it and am learning a lot about the art). Anyhow we started down around Point Lobos with Jeffers, moved over into theValley with early Everson, then up into the mountains with Rexroth & going north with the earlier Snyder and Roethke. Coordinating poets, painters and photographers where possible (Weston, Morris, Graves , Toby). Anyway, in a couple of weeks, we’ll be coming down the coast to finally get into the City.

Here’s where I’m hoping we can get together. I’ll be having the class read ON OUT, and The Song Mnt. Tamalpais Sings. What I want to propose is bringing the class over to Marin County, say either Muir Beach or somewhere on the Mountain and spend a morning with you reading and rapping about the poems, any way you would like to handle it. I’d like to suggest Monday, March 22. About ten in the morning. Some students have studio classes in the afternoon, so I don’t want to cut them out, in case the thing should extend into the afternoon…

Sincerely

Stephen Vincent

3/20/71

Dear Stephen,

Unfortunately I’ll be in the state of Washington till April 1st or maybe 15th. The class sounds really great & I regret to have to miss it. I’ll phone you when I return to S.F. Is it possible to do my part in April? Ginsberg will be in town at the end of April, too. I can be reached c/o Wm. Yardes, 606 Englebert Rd., Woodland, Wash., till April 1st. I’ll be talking to you soon.

Lew Welch

II

- WOBLY ROCK RE-FELT

- Wobly Rock for Gary Snyder

- “I think I’ll be the Buddha of this place”

- and sat himself

- down

- and sat himself

- “I think I’ll be the Buddha of this place”

- 1.

- It’s a real rock

- (believe this first)

- It’s a real rock

- Resting on actual sand at the surf’s edge:

- Muir Beach, California

- (like everything else I have

- somebody showed it to me and I found it by myself)

- Hard common stone

- Size of the largest haystack

- It moves when hit by waves

- Actually shudders

- (even a good gust of wind will do it

- if you sit real still and keep your mouth shut)

- Notched to certain center it

- Yields and then comes back to it:

- Wobbly tons

It’s Monday morning. All weekend I’ve been looking for Lew Welch. A month ago we exchanged letters, tentatively agreeing that he will meet the class. However, we have lost touch. I fail to get a letter off to him in time to his temporary address in Washington. The letter I leave at Serendipity Bookshop gets rightly forwarded to Gary Snyder’s place above Nevada City while I’m off to New York at Easter, but apparently doesn’t get back to him. Back in the Bay Area, I work on a few leads. Jack Shoemaker, at the Bookshop, says to try the No Name bar in Sausalito. A week ago I start. One day one bartender says he saw him on Saturday. But that he’s gone to Nevada City. A couple of days later another bartender says he saw him last night. I leave a message for him to call. No luck. On Friday night I hear Allen Ginsberg has come to town. Lew mentioned that in his letter. Perhaps they’re together. Ginsberg must be going to the Peace March. On Saturday at the Polo Grounds, I look all over for Allen, half expecting him to be leading chants in the middle of somewhere. No luck. Just people, people, people. I call City Lights and get a clue that he might be staying up at the publishing office, up on Grant.

On Sunday afternoon, I go to the door, but no one is there. I go to the store. Ask the clerk who knows nothing. I write a note. While I’m at it, a short olive complexioned guy with a girl who has a woolen cap pulled tough style over her head, come in. The guy, happy smile on his face ups to the counter and says, “Have you seen Allen,” as if he were getting ready to put his hands on a gift. The young oriental clerk with shoulder length black hair, says, “No.” The guy, almost taking a dance step back, says, “Is he staying over the publishing office?”

The clerk, honest, says “I don’t know. I just heard he got into town.”

And I’m flashing, maybe I’m gonna pin this note on the wrong door, if Ginsberg is upstairs. So, I say to the guy, “Say, I’m trying to get a note to Allen. Did you say that place is upstairs?”

The guy, continuing to back out the door, puts a slow smile on his face, as if he were courtier to the now secret guest, says, “I’m afraid I can’t tell you that.” Smack.

“Elitist.” The word comes flash out of my mouth. Bam. He backs out the door where his hard chick is waiting. “Elitist,” she repeats, as if trying to disown the accusation. But it’s only re-enforced when it bumbles out of her mouth. They split.

Lew Welch used to speak a lot about only writing what is ‘accurate.’ That made me feel foul after.

I leave the note on the front door, asking Allen to please call, if he can help in the search. I get home and wait. Nothing happens. I give the No Name one more call. Yes he was in Saturday night. No, they don’t know where he’s staying. I simply give up, saddened by the failure of the whole process.

About ten students show. We all decide to go anyway. We’ll go to Muir Beach and find Wobly Rock. Four cars and we’re over there by ten o’clock. Don, one of the students, brings out a big bottle of Red Gallo, and between us we have homemade bread, oranges and apples. It’s an overcast day, what the radio calls ‘high clouds,’ but not too cold. I’ve been told that the rock is at the south end of the beach, so I figure we can find it from the evidence within the poem. (Charles Olson, I hear, thought Wobly Rock was Lew’s best thing.) So off we go across the curve of sand, then into rocks, until we come to a large rock that stands on the edge of water, below the dirt cliff, at the beginning of the beaches inward curve. I look around its base. Sure enough the rock is wedged into a crater of several rocks. And yes, before this bare trunk got wedged between the high rock and the crater, it must have rocked back and forth from the pressure of the waves, at least when they began to lap hard against it, during high tide.

“This is it. This must be it,” I announce, as if I just discovered a lost landmark, or an old gold mine. Suddenly I’m self conscious in the role of teacher. The first section of the poem says, “Shut up.” And here I am talking about it, a little like the morning, after sleeping in the temple of Athena at Delphi. I woke to find an Encyclopedia Britannica filming crew making a film of the grounds, the members of the crew mimicking the different gods they remembered from school, but that I thought still inhabited the place. I was still too afraid to tell them to ‘Shut Up.’ But even now, at the Rock, with Lew’s books in hand, I still feel like the uptight French tourist being led around by his Guide Bleu.

Anyway I don’t feel right about it. It is comic that the Rock in the book wobbles, and the one here doesn’t. And I want to read the poem. And it’s a jarring contrast. The poem suddenly feels very innocent. But I work my way through it, speaking as loud as I can, giving language space there on the rocks and ledges that surround the stone. Here and there I stop to give explanation as best I can of a Zen means of perception. But it still doesn’t feel right and I wish to hell Lew were here to justify this situation I’ve put myself in. Something is all wrong. Instead of getting right away into the reading of the poem, we should have climbed around, and got a literal feel and respect for the place.

I’m doing all this standing up with my back against a shelf of rock that faces Wobly. Some students are standing, others have sat down on different stones, or on the log up close to the cliff. To try and make my sense of relationship to the poem more human, I finish this part of the morning by reading part of a little thing I wrote on Lew’s book, ON OUT, a few weeks back:

…in Jeffers (Robinson) the plea is to enter nature, become divorced from human kind. Nobility is the vital identification with energies that emanate from natural and non-human forces. Man’s presence is most often viewed as evil, plunging the planet into failure. The tone is pessimistic, excessively individualistic, isolationist. Welch comes close to Jeffers when he views how man exploits the environment, turning the planet to smoke. However he sees a community of possibility. When people are free, i.e., relate to nature unselfconsciously, there is a balanced achieved, man becomes an implicit and beneficial element of nature. The sea within becomes the sea without. A harmonious intercourse. A bliss achieved.

Much of ON OUT is designed to explore perception. How, or what is the right way to view the world, the immediate location of our existence. What is accurate. Notably he rejects artificial impositions, things that get in the way. Obviously he would be against surrealism, closer to a ‘rose is a rose is a rose.’ Again, the rose within yields to the rose without.

Then it relies on an eastern meditative stance. Exhaust all excess materials out of the head.

Make the moment of contact with reality purest by not thinking of all that other shit, past tenses and wishes.

The word is purity.

So I shut up. We bring out the bread, wine, apples and cheese. And people begin to feel the place out.

I sit watching and eating, trying to chew the rhetoric off my tongue, and just get a sense of being there. The grey above begins to break and sun comes casually through on the waves and rocks. I sense the ocean more and the light sharpens the white color of the foam on the waves, as the tide begins to lap in. But, good academic soul, I keep running into irony. In section four of the poem, it begins:

- Yesterday the weather was nice there were lots of people

- Today it rains, the only other figure is far up the beach

- (by the curve of his body I know he leans against the tug of his fishingline:

- there is no separation)

Below the flat rock where the wine and food sit, I reach down and pull up the broken handle of a fishing rod. Craig, looking between two other rocks, finds the split and shredded yellow-white bamboo of a complete rod. We give a weird chuckle at what seems like another break in the poem. While Jim and Donna are up climbing around the edge of Wobbly, they discover a dead seal and say, “God, it stinks!” Later Jim comes from another sandy part of the beach with little pieces of plastic, from bottles and such, that he says he keeps finding all over the place. Jeff and Ken, both from New York, lean against a boulder and talk about New York. Only Wen, a Chinese girl from Hong Kong, who rarely ever speaks, appears content. She is wearing an orange sweater and brown corduroys. She sits on the rough-shaped stones and, first, juggles two oval-shaped stones back and forth in little loops in the air. I ask her if she knows how to juggle. She says no and stops and begins to build what looks like one dimensional pagodas beside her knees. It’s nice to watch as Don, the large photographer and I talk about sailing and photography, and how photographers can be exploitive and sadistic. He tells me a story of how his class came out to this same place a month ago with three models. And how one must have really been loaded on something, the way she kept moving around all afternoon, jumping across and diving into the surf. The models were all nude and this one scratched herself horribly, scraping herself bloody against the rocks. But how she was the best one, the way she got into it and kept moving.

“It sounds horrible,” I say.

“It was.”

And now all the students come back, except Wen who’d wandered by herself down the beach. The sun is out full now and she’s picking up rocks and going through the slow motions of discuss thrower. I pick up Lew’s most recent book, THE SONG MNT. TAMALPAIS SINGS, and between the stanzas, as I again read out loud, I occasionally look down the beach at the orange and brown figure going through the careful smooth motions of throwing the rocks. There is such a disciplined, quiet grace about her whole sense of movement.

From the book I take, “SONG OF THE TURKEY BUZZARD.” I read the poem strong. The fresh air has finally filled and relaxed my lungs, so I feel deeply into the making of each phrase. Everything in it feels tangible:

- I hit one once, with a .22

- heard the “flak” and a feather flew off, he

- flapped his wings just once and

- went on sailing.

- Bronze

- (when seen from above)

- as I have seen them. All day sitting

- on a cliff so steep they

- circled below me, in the up-draught

- passed so close I could see his

- eye.

- However, as I tell the class, the completion of the poem really disturbs me;

- II

- Praises Gentle Tamalpais

- Perfect in Wisdom and Beauty of the

- sweetest water

- and the soaring birds

- great seas at the feet of thy cliffs

- Hear my last Will and testament:

- Among my friends there shall always be

- one with proper instructions

- for my continuance.

- Let no one grieve,

- I shall have used it all up

- used up every bit of it.

- What an extravagance!

- What a relief!

- On a marked rock, following his orders,

- place my meat.

- All care must be taken not to

- frighten the natives of this

- barbarous land, who

- will not let us die, even,

- as we wish.

- With proper ceremony disembowel what I

- no longer need, that it might more quickly rot and tempt

- my new form

- NOT THE BRONZE CASKET BUT THE BRAZEN WING

- SOARING FOREVER ABOVE THE O PERFECT

- O SWEETEST WATER O GLORIOUS

- WHEELING

- BIRD

And I read to the class what I had written in response:

Lew’s tone changes here, Religious, priester taken his vows, no more questioning, but into that Jeffers thing so deep that the world is beyond human repair, because of basic, human flaw (i.e., witness what we have done to the planet). Only the vultures, again as in Jeffers, are pure, clean. Though he doesn’t reject what has been joy in his own life, the negative thrust is there; the only dignity that remains is owned by those birds who turn human garbage into the beauty of their own flight. Though I think the poem stands on a language of its own, I don’t see the point of view as terribly different from Jeffer’s poem, Vulture:

- … how beautiful he looked, veering away in the sea – light over the

- precipice. I tell you solemnly

- That I was sorry to have disappointed him. To be eaten by that beak

- and become part of him, to share those wings and those eyes—

- What a sublime end of one’s body, what an enskyment;

- What a life after death.

But the class disagrees when I say the poem comes off to me as weird death wish that I can’t understand. Welch is still in his forties, and seems to me a strange time for a man to be making a last will and testament. When I ask what people feel about the poem, and if they agree with my sense of it, several people shake their heads, as if my viewpoint is too narrow. Paul seems to sum up the objection quickly. “As I see it,” he says, “the poem is just one more acceptance of Death,” and the poem, from his hearing of it was, “more just an acceptance of the cycle of Death and it was liberating to listen to because it didn’t try to reject Death as part of the cycle of things.” The way he paints it is that both Lew and the poem are at just one point in a large pattern that is only partly visible to us. And the act of the poem is just preparation and acceptance of the next step.

Suddenly the poem becomes Asian again. Bigger than I had ever been willing to accept it or see it. My original response now was coming off as the thin, Western humanist. That is, operating out of a concern for daily and secular obligation. (Maybe that’s the answer that lies behind Lew’s refrain, ‘What are we gonna today/today, today, today’). In any case, in a funny way, Paul’s response brought me out of the bind I felt myself in when I brought my class down to the rock in the first place. That is, my weird consciousness of having to perform some academic pedagogic duty, or, literally do something to the stone to make it valid. But now gradually I was getting to a point where I could see things in a way that wasn’t always ironical (the rock that wouldn’t rock, etc). Of course Wen had already begun to locate me there, to make the event literal, as opposed to literary.

So, since all ears feel open, I finish by reading all of the HERMIT POEMS. Then I get up and really begin to enjoy the place, the feel of wind, the sun. I climb up the side of Wobly, check out the smell of the seal, its skin rotting in the crevice of the crator. Everybody is climbing all over the place now, up the cliff, the other shelves of rock. I climb up one shelf, sit Yogi style, and figure this is the one the poem was meditated upon. A full view of the beach, the rock, and the way the ocean ripples across the stone boulders that appear planted in the sand:

- 2

- Sitting here you look below to other rocks

- Precisely placed as rocks of Ryoanji:

- Foam like swept stones

- ...

My mind flashed back to Wen building the little rock houses. Lew is right. They do look like photographs I’ve seen of boulders in Buddhist rock gardens:

- Or think of the monks who made it 4 hundred and 50 years ago

- Lugged the boulders from the sea

- Swept to foam original gravel stone from sea

- (and saw it, even then, when finally they

- all looked up the

- instant after it was made)

And there is a beautiful flash that takes place in my head and body when I suddenly equate the fact of the poem with the glazed water and foam drifting between the black boulders and sand. It’s so rare to find. I hear the word ‘legitimate.’ Any how.

After a while, it feels like ‘time to go.’ I turn around and look up the cliff. Ken, the New Yorker, is up in a tall, shallow cave. His elbows are at his sides with his hands up in the air, looking like the tucked in wings of a vulture. Everybody else is climbing around the beach playing with stones, or just watching the movement of the ocean. Nobody has a watch when I ask what time it is. Somebody says, “How does a mountain or a rock tell time.” Then I say, Wouldn’t it be surreal to put a watch around a mountain.” And somebody says, “we better go.”

We pick up all our garbage and split, several of us saying it would be better if we had all our classes

Outside

III

The Monday after the visit to Wobly Rock, I get a telephone call in the middle of the class. It’s Lew. His voice sounds flat and distant. It’s difficult for me to talk because we are in the middle of an hour with Jack Gilbert who is talking about his sense of the fifties. Lew wants to know if he can still come to the class. I have to tell him it’s too late. David Meltzer is scheduled to come the next week, and there are no classes after that one. Actually it’s more complicated. In truth I’m telling him he can’t come because we already spent two weeks on his work, and we have three or four more poets to cover. A history of local literature in miniature that, at one time, he could have parodied (as in, “A Round of English” for Philip Whalen in ON OUT). At the same time I feel guilty because I’m telling a human voice that I value that he can’t, even if he wants to, come up with his goods anymore. I tell him we went to Muir Beach last week and I wrote something on it and would he like it, if I sent it to him? He says sure and to send it in care of Don Allen, his editor. I complete the call by saying we’ll get him a reading this fall at the Art Institute to which he seems interested. Then I get back to the class and Jack Gilbert.

That was the first Monday of May and the last time I ever spoke to him. Three weeks later, on May 28, the San Francisco Chronicle reported his disappearance:

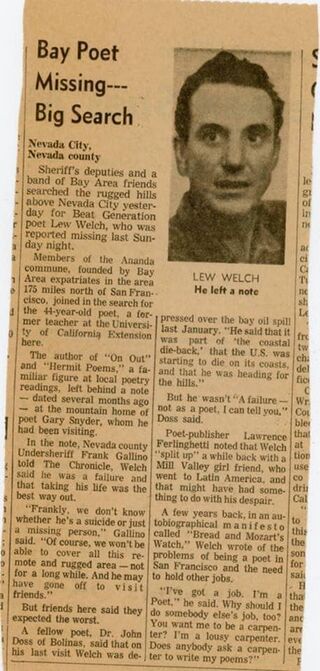

BAY POET MISSING – BIG SEARCH Sheriff’s deputies and a band of Bay Area friends searched the rugged hills above Nevada City yesterday for Beat Generation poet Lew Welch, who was reported missing last Sunday night….

Early in April, when I first tried to get in touch with Lew and had been reading his works as closely as I could, I had this dream:

It’s not a happy dream. Actually cold. I’m on a beach that I’ve never seen. A blankness, an unkempt quality about it. It is an era of desolation. I’m waiting there for no particular reason. Like there is nothing else to do. I’m with a couple of friends but our friendship does not even seem to be particularly significant. Then Lew shows up.

He’s dressed only in his trunks. A tall, slender figure, tanned by the sun. His head is higher than mine, and his neck is craned back like that of a horse permanently broken by unkind reins. It is impossible to establish any sense of personal location with him. His face will not receive the personal or, any longer, reciprocate with such. He does not say a word.

So I am still lonely on the beach. He’s merely a new figure on the beach for me to watch. He knows what he wants to do. There is a low platform made out of white driftwood. It’s on the upper-edge of the beach facing the horizon. It’s early afternoon. He walks over and out to the platform where he lies down with his knees bent up in the air.

It’s the end of his part in the dream. It’s as if he’s waiting to be carried across the sea in some ancient rite. There’s no use talking anymore. It’s only time to wait, to bake in the sun, before taking that ultimate journey.

I lose interest in watching. There is a fence across the beach. On the other side is the beautiful wife of an ex-friend. She is smiling that I come to her. When I go around the fence, we take hands and begin to dance, like spiders, back and forth across the hot sand. Lew’s muse. She must be, Lew’s muse. He has left her. I pursue her in love. She is black. The dream dissolves in dance.

In May, and over the summer, there are reports in the newspaper and by word of mouth that Lew has re-appeared. That he was seen in Nevada City, that he was in Sausalito, that people had talked to him, etc. By September, it’s obvious to most, that he’s never coming back.

How did we get here? How did we get to this voice? Why Lew Welch? Why should he be important to me, to us?

For me it goes back to 1965. I was in the City, just beginning to hear my own voice, in my own poems. I was just 24 and had two poems published. A very tenuous entrance into the world of poets. I and my friends had given a couple of readings at the Blue Unicorn, a coffee shop on the edge of the Haight, where I and my girlfriend also lived. None of us know where we are going. I was in the writing program at State, but that was coming to an end. In the world there was the war, the draft, the question of what to do. My body refused to continue to go to school. In music there was Dylan, Coltrane. But they were far away. Local examples seemed remote. Spicer, Loewinsohn, Meltzer, Snyder, Whalen. They all seemed large and unapproachable. Especially to those of us still in school.

Actually I only met and talked to Lew once in my life. I shouldn’t say talked. I really listened, but maybe it was the first time I learned I could get high listening to someone, just through rhythm and voice. It was in April of ’65. I had just heard him read and sing in the Gallery Lounge at the College. It was a benefit for Dizzie Gillespie for President campaign. There, I had loved it, the phrasing of his line, a cross between song and natural voice. Plus, what he was using in terms of content, related a lot to the feel I got from living in the City. The language was airy and salted, from somebody who really liked to relate to the public life of the street. It had a clean, liberated feeling about it. Plus there were also poems about driving cab which I was also doing at the time. Like the poem “IN ANSWER TO A QUESTION FROM P.W.,” how it ends:

Like the sign over the urinal: “You hold your future in your hand.”

Or what the giant negro whore once said, in the back of my cab:

Man, you sure do love diggin’ at my titties, now stop that. We get where we going you can milk me like a Holstein, but I gotta see your money first.

Lew was someone who actually had dug and given form to what I was digging, listening to all those stories out of the back of the cab, while I was doing it for a living.

So one night when I and Margaret (my girl friend at the time), and Tom Schmidt and Maria and Bill Howard, three other friends, were in the Juke Box, a bar on the corner of Haight and Ashbury, when I saw Lew up at the bar, it was about ten o’clock, I naturally went up and invited him to come back and sit and talk with us. When I got to the bar, I had to wait a minute. The Juke Box was on, something by Dinah Washington, and he was busy describing to Harry, the black bartender, how Dinah’s voice was sounding just like a trumpet at this one point in the song. It was obvious that he not only loved music, but lived in relationship to it like a warm coat that kept his feelings alive and intact. The pleasure he took in depicting the quality of her voice, made the music seem like a nipple that he sucked with precise and everchanging delight.

But he was happy to come back with me to the table. He was terribly high from teaching. He had just come from the Medical Center where he was giving a course on Gertrude Stein. It was the sound of a voice of a man in love. It was ten o’clock and for the next three hours he rapped on everything imaginable. Starting with Gertrude, moving to music, then relating to poets, he talked of people, things he had done. Much of it I guess was preachment. He was asserting a way to live. Definitely not like his mother, gripping his hand out in front of us, “She wanted us to be clean as a bar of soap. She’d even say that!” How he was in awe of John Handy, the alto-saxophonist, who knew so much about the history of jazz, that he was still afraid to approach him. And how poets could be like jazz musicians around younger artists, cooking as hard as they could to keep the younger ones out of the circle. Six years later now it’s hard to recapture content. I just know and remember how well it felt to listen. Our questions and remarks were like drum beats behind the musical pictures they helped provoke him to draw.

I felt great for at least three days after. Energy coming out of every pore. Completely free from all that City Paranoia. He’d given us all a good start.

We got to literally see each other a few days later. At that time Doug Palmer and Gary Snyder had started an IWW local for poets and other artists. On that Saturday, down in a Second St. alley loft, we had a benefit to pay the rent, I was one of several people scheduled to read, Lew and Gary were the top readers. Since I was driving taxi, I could only come in for an hour in which I could read and listen some. I read at nine-thirty and Lew was there. I read for ten minutes as well as I could, or perhaps the best I had ever done. When I finished, there was a good applause and I felt pleased, in fact proud. Lew was by one wall with a couple of people. Instead of walking over to him, I just looked across the room and smiled hello, half way imagining that he’d walk over to me and say what he thought. He didn’t. He just raised his eyes, with a tight lipped grin hello. He looked pleased. But I still didn’t go over. My own pride holding me and turning me to talk to a friend.

I remember that. Anyway, I soon left the City. The Peace Corps as my out. Two years in Africa, Nigeria, I shared ON OUT with anybody I thought liked poetry, often telling my friends of that night in the Juke Box.

Coming back to the City, however, in 1968, the relationship stopped feeling the same. Though I heard through other poets Lew was not writing any new stuff; the bottle was overtaking him. I still held him in the same kind of awe that I believe he held for John Handy. I was afraid to get close, because I felt he knew so much, and I wanted to know more before I approached him again. I didn’t want to be in the position of disciple. At the same time, the city and the country were going through heavy changes. The Panthers, the Strike at State, the dissolution of the Haight-Ashbury, changes from acid to speed, everything going at collision force, as both political and artistic off-spring from the revolutionary prophecies of the late fifties and early sixties, it was getting terribly difficult to keep our heads above water. In getting away from poetry, Lew had gotten into visionary prose. It was always beautiful to read, the few pieces that I saw in the Digger papers and the Oracle. He had become a cross between an urban anthropologist and ecologist. I remember he read one of them at an event in the Nourse auditorium. The passage always sticks in my mind where he talks of walking through the Mission with Philip Whalen and he goes into a bar to take a leak and his shoes are an inch deep in piss on the john floor. It was his metaphor for decline and fall, the erosion of San Francisco. But everything he was writing was going in that direction. Out from the City. Long hairs, in new families and tribes, leaving for the country, to create new and decent lives, while the cities destroyed themselves. On the surface, the vision of survival was optimistic. It was still as if the holiness of the vision that takes place in Wobly Rock could come to pass. But underneath it was despair. It might have been deeply personal, but in rejecting the City, he was also rejecting the source of his music, and the source of his language. The voices and sounds that fed him were from the City, and he no longer felt he could be fed.

And I was, and continue, to try to hold on in the City. And the visions, no matter how accurate in description, now failed to pull me. I wanted to hear the old voice singing a more personal song. If the social whole was quite literally falling apart, revolutionary energy aside, I wanted to hear a local, an immediate voice help get us through, at least, one to one. But in 1969, I hadn’t even got that far yet, I was, in consciousness, somewhere between the Panthers, the State Strike and People’s Park. I had stopped writing. The answers for me had become urban and collective. I wasn’t heading for any woods.

Then I didn’t hear of him for a long time. By Nixon year II, energies on a social level had really begun to collapse. Collective visions had become a set of fictions, or, at most, commercially co-opted. I had begun writing again. Quiet exile in Berkeley and Oakland after a heavy house rip off in the City. My despair.

Then, out of nowhere, it happened. An ecology benefit that was given in the Pauley Ballroom in November of 1970. It was probably the best poetry reading to a large audience (at least a 1,000) that has been given in the Bay Area in some time, Gary Snyder, Howard McCord, David Meltzer, Mary Korte, Keith Lampe and Richard Brautigan. There, Lew read much of THE SONG MNT TAMALPAIS SINGS. It was an incredibly beautiful performance. The voice sounding pure and full, so that you could sense the audience rising, falling and moving in the direction of the line, language being the hypnotic master of the event. He took us up the mountain and made it speak in such a way you could hear the wind touch the shapes and crevices of the rock:

- This is the last place. There is nowhere else to go.

- Once again we celebrate the great Spring Tides.

- Beaches are strewn again with Jasper,

- Agate and Jade.

- The Mussel-rocks stand clear.

- This is the last place. There is nowhere else to go.

- Once again we celebrate the

- Headland’s huge , cairn-studded fall

- into the Sea

- This is the last place. There is nowhere else to go.

- For we have walked the jeweled beache

- at the foot of the final cliffs

- of all man’s wanderings.

- This is the last place.

- There is nowhere else we need to go.

There was something convincingly Holy about the experience which now makes his final despair, no matter what might have been his personal problems, be very legitimate. When you have found the Altar, and through the Altar, you hear such pure, life giving sounds, it must be next to impossible to acknowledge and live with forces that you are convinced are going to completely wipe out that Altar, or what has become the singular source of your life.

IV

The ecological awareness must have worked heavily to destroy him. The other forces are more clearly viewable in the interview with David Meltzer. But, it appears, I’m having trouble ending this. What did he mean to me? Why do I feel like I’ve grown away from the first offering? Why do I still want to stand back?

I hope this comes off as praise. What he uncovered and opened up, the energy there gave me my first genuine lift into the whole act and love of poetry, not as a diversion, but an on-going statement of life. It’s just that the statement finally got too narrow for me. In a sense Lew became his own mountain, high and removed from the world of the City, the language of his which first attracted me to both the man and his work. Indeed he was deadly accurate about the forces of erosion, those who would eliminate the possibility of what is gentle and pure and only act in terms of greed and destruction, the vision or the place of the vision simply got too narrow. Not that he lost consciousness of the world, but he lost that urge to participate, to try and become at one with us in participation in that world. In short, we no longer need the voice of the teacher (and God knows we’ve had too many martyrs). We need, if I can preach, voices that can listen to each other and, again, make possible survival here.

But let me end this in praise. Praise for a voice, a mountain of a voice. I loved to hear.