Raising the Stakes: Complete Disarmament

Historical Essay

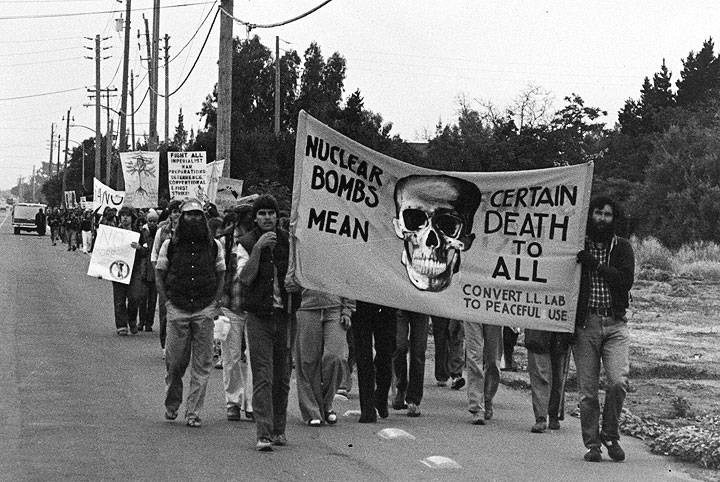

by Tom Athanasiou, James Brook, Marcy Darnovsky and Steve Stallone, with thanks to Louis Michaelson and Bob Van Scoy; originally published in the Ground Zero Gazette, an August 1981 insert into It's About Times, the Abalone Alliance newspaper

The demand for complete nuclear and conventional disarmament is a much more direct challenge to ruling institutions than most other reforms. Because the power of every political and economic elite ultimately depends on the force of arms, the demand for disarmament calls into question the existence of the nation-state itself. This implies looking at the need for radically different forms of social and economic organization.

Photo: It's About Times newspaper

This is not to say that all strategies for ending the arms race that fall short of social revolution are worthless, but rather that the disarmament movement must find a politics sufficient to the logic of its own demand—not an easy task. Unfortunately, a strange combination of pragmatism and desperation often leads the disarmament movement to embrace the most moderate and simplistic solutions.

There's a political aspect to arms control that warrants careful consideration: The state offers the prospect of arms control to disarmament movements in order to weaken them, confuse them and shut them up. The US recently conceded to hold arms control talks with the Soviets, for example, but only after European governments repeatedly insisted that the negotiations were necessary in order to sell the new weapons to their openly skeptical populations.

It's a good bet that a powerful movement that unequivocally demanded total disarmament would elicit plenty of compromise proposals from the ruling elites themselves. These proposals would be made to seem “reasonable” and “practical” and might reduce the number of warheads, but they wouldn't seriously reduce the threat of mass destruction.

In its attempts to appeal to everybody without offending anybody, the disarmament movement also plays the game of reasonableness and moderation. The "respectability" insisted on especially by the church and pacifist-influenced wings of the disarmament movement is supposed to avoid alienating and frightening the many people who have never been politically involved. But the real divisions in society—for, example, between those who fight the wars and those who start them—are politely ignored. A movement too timid to confront these divisions may well wind up preserving them. A movement afraid of open opposition won't be effective in the long run.

The recent efforts on the part of American disarmament activists to try new and different approaches are heartening. But for the most part they all stay within a framework of cultural assumptions that may be part of the problem. The movement will never overcome its current insularity unless it becomes culturally open to many different kinds of people. The granola-and-limp-rock image that caricaturizes the antinuclear power movement, for example, has smothered its vitality and crimped its ability to draw in people whose lives aren't so "simple" and "natural."

The disarmament movement, rather than appealing to intelligence, self-initiative and inclinations to raise hell, spends itself on herding the masses around from ballot box to boring rally to Bomb therapy group. This thoroughly run-of-the-mill institutional approach may be well meaning, but it’s unlikely to generate any excitement and is almost sure to drain the life out of any spontaneous resistance to militarism. The organizers may elect a Congressperson here and there but disarmament will remain one of those beautiful impractical dreams—like clean air and a cancer-free old age. Or even an old age.

When the disarmament movement does turn on the hard sell, it resorts to horrifying its audiences with the gory effects of nuclear holocaust. It believes that by violating the taboos against thinking and talking about nuclear disaster it can break the barriers of denial and "psychic numbing." But because it does not incite anger at the perpetrators and planners of mass destruction and avoids "politics" and hard analysis of the social roots of war, horror-mongering, can backfire. It can induce an undifferentiated terror—the Bomb becomes supernatural and inevitable rather than a consciously manufactured instrument of social control.

Dr. Helen Caldicott, for instance, has adopted nuclear hysteria as an organizing tool. But is war primarily a medical and psychological problem, as Caldicott claims? Doesn't the shock treatment tend to inhibit rational consideration of the issues? Following the doctor's orders may be a first step in the wrong direction.

In their search for credibility, many disarmament activists accept and promote the idea of "legitimate national security." This rhetoric relegitimates the nation and nationalism, the very concepts that have always served to promote universal identification with the interests of the ruling elites and to justify war. The national “we” is a deadly pronoun.

To oppose resurgent militarism with pandering appeals to national security is playing with fire. The managers of consciousness manipulate patriotism to their own advantage, as the sudden remission of the "Vietnam Syndrome" after the dose of American nationalism surrounding the events in Iran showed.

This poster was placed in BART trains during the early 1980s, dramatizing the absurdity of claims of surviving nuclear war.

Pressure groups or popular movements?

A successful disarmament movement must defend its autonomy and refuse to be sucked into the kind of politicking that converts radical dissidents into reasonable constituencies. To be effective, it will have to change the definition of what is reasonable.

Short-term goals must be chosen so as to encourage radical perceptions and actions, not reliance on a political process that, by absorbing and diffusing opposition, functions as a key part of the apparatus of social control. Immediate demands should be grounded in a critique of the class relations underlying war and empire. Then we could at least imagine a disarmament campaign growing into a movement capable of confronting the roots of war.

In contrast to these sorts of demands, consider the Nuclear Weapons Freeze. The Freeze is a product of desperation on the part of disarmament activists over destabilizing weapons like the MX, the Trident and the Cruise missile and destabilizing policies like counterforce.

Advocates of the Freeze, which is presented as bilateral, simply assume that the USSR would accept it. This assumption, which appears highly dubious to many Americans, refuses to acknowledge the existence of groups within Soviet society that promote and benefit from militarism. Public pressure is suggested as the means of forcing the US ruling elites to accept the Freeze, but no mechanism is proposed for convincing or coercing Soviet leaders to agree to it.

Even if the Freeze was implemented, it would do little to alter the structure of international power. The ability of the superpowers to wage war would not be seriously impaired. Thirty thousand strategic warheads on "our" side—and a comparable number of Russian nukes—are plenty. Interventions in any country that didn’t have its own nuclear arsenal could still be undertaken with relative impunity.

Clearly we don't yet have the collective power to successfully demand a Freeze, so the strategy must be evaluated first of all in terms of the basis of the deeper political education it will provide and the kind of movement that will be encouraged by its promotion.

The Freeze, like many other disarmament strategies, is based on the political theory that the most successful demands are those that appeal to the lowest common denominator. It's obvious that the disarmament movement must, reach much greater numbers of people, but the Freeze seems to share the assumption that inoffensiveness is the best selling point. It is possible that focusing the movement on a limiting demand like the Freeze will tend to eclipse more radical, more inspiring, more substantial responses to our collective predicament.

The power of the disarmament movement will stem from its ability to disturb, paralyze and delegitimate important social institutions, for example through protests and worker and student strikes. Its resources are its commitment to the widest possible democracy in decision making, unlimited and public discussion, and an aggressive pursuit of its aims, rather than the acceptance of symbolic stop-gaps.

Disarmament will remain an impossible demand as long as the movement is kept on a leash, nationalism is masqueraded as opposition to war and the frank discussion of the real causes of war is suppressed.