Fight to Remediate Hunter’s Point Toxicity

Historical Essay

by Dr. Ahimsa Sumchai, 2004

Originally published in The Political Edge under the title "Put Your Head In It!, 2004"

View from former Avisadero Point over the abandoned Naval Shipyards at Hunters' Point.

Photo: Chris Carlsson, 2021

| Hunters Point is the site of extensive pollution, home to hazardous materials and polluting industrial plants. Over decades, public officials have disappointed residents through their failure to effectively clean up Hunters Point. A first-person perspective gives insight into how, particularly after mayoral candidate Matt Gonzalez lost the race in 2003, the community had to fight back against redevelopment and continued power plant operation. |

I grew up in southeast San Francisco. We lived at 27 Dakota Street in the Potrero Hill housing projects, 1726 Sunnydale in the Sunnydale housing projects and in a house on Thomas Street in Bayview. After graduating from Woodrow Wilson High School and San Francisco State University, I attended medical school at the University of California at San Francisco.

In 1982 I became the first African American woman to train in UCSF’s prestigious department of neurological surgery. I am forever left with the memory of a recommendation during the stress and frantic hurry of my surgical internship on how best to stop a closing elevator . . . put your head in it!

In the beginnning the Muwekme Ohlone Indians lived in harmony with the land on the promontory extending eastward into the Bay in southeastern San Francisco. They called it Sea Shell Point. The Ohlone Indians thrived on a diet rich in shellfish and decorated the burial mounds of their departed loved ones with sea shells. These shellmounds are documented in the archeological history of the region. The Ohlone Indians have survived for 2000 years and today are locked in legal battles over the ownership of the federal lands on which the modern day Bayview–Hunters Point district is situated.

In the 1800s Spanish explorers sailed into the Bay and named that promontory of land Point Avisadero. By the mid-1800s the California Gold Rush had ushered in an era of economic prosperity and a boom in commercial sea transport. The southeast peninsula became a vital seaport for the arrival and departure of goods, merchandise and supplies on Clipper ships for the “49ers.” The Alaska cod fish industry flourished as did the Chinese shrimping industry.

Hunters Point operated as a commerical drydock from 1869 to 1939. In 1939, eleven days before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy acquired the land and until 1974 used it for shipbuilding, repair, maintenance, and submarine servicing.

One fateful morning in April 1945 the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard was thoroughly evacuated for the arrival of the USS Indianapolis. According to the ship’s captain, the components of the atom bomb that was ultimately dropped on Hiroshima were picked up and transported to an island in the South Pacific.

Parcel E, the most toxic area in the former Naval Shipyard, seen here from Candlestick Point State Recreation Area.

Photo: Chris Carlsson, 2006

By the mid-1950s, 8,500 civilians were employed at the Hunters Point Shipyard. Many of these shipyard workers were African Americans recruited from the southern states to work in the shipyard industries during the World War II era. The navy deactivated the shipyard in 1974. In 1989, following extensive environmental investigations, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency placed the shipyard on the National Priorities List, thus designating it a federal “Superfund” site, making it eligible for federal funds to clean up toxic waste.

There are three generations of longshoremen in my family. My father, George Donald Porter, was a college-educated “walking boss.” A handsome guy with a bright smile and a zany sense of humor, one morning in February 1992 I walked into his bedroom and found him dead. He was fifty-six years old. He had pulmonary asbestosis; with his chest Xray as evidence, a class action civil suit was ultimately settled. I was very angry for about five years. My father’s death changed my life and changed my career direction.

In 1997, as an attending physician in the emergency department of the Palo Alto Veteran’s Administration Hospital, I took charge of the Persian Gulf, Agent Orange, Ionizing Radiation Registry. The VA Hospital’s health care network boasts the nation’s largest and most comprehensive toxic registry. My background in emergency toxicology, civil litigation, and environmental sciences, coupled with a two-year research fellowship at Stanford University prepared me for what was to become the most challenging experiences of my professional career, volunteering as an environmental activist in the Bayview–Hunters Point District of San Francisco (BVHP). The community I grew up in, the community I love.

Environmental Racism

The first health study of San Francisco’s heavily polluted Bayview-Hunters Point found that chronic illness hospitalizations were nearly four times higher than the state average. Doctors from the University of California at San Francisco and the city health department studied records from 1991 and 1992 and found that hospitalization rates for asthma, congestive heart failure, and emphysema were 138 per 10,000. The statewide average was 37 per 10,000. Rates of hospitalization and premature death for children were found to be markedly high and according to Dr. Kevin Grumbach, a UCSF researcher who headed the study, “I would not be adverse to saying the environment is a smoking gun.”

Bayview–Hunters Point contains four times as many toxins as any other city neighborhood, according to a 1995 city health department study. The area has 700 hazardous waste facilities, 325 underground petroleum storage tanks, the state’s oldest and most polluting power plant—the infamous PG&E Hunters Point Power Plant. A second power plant located in nearby Potrero Hill is operated by the private corporation Mirant. Additionally, BVHP is the site of the sewage treatment plant for the city and county of San Francisco; it is a state Superfund site and one of the most extensively polluted federal Superfund sites in the nation.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

I serve on the Restoration Advisory Board of the Hunters Point shipyard and chair the Radiological subcommittee. The Hunters Point Naval Shipyard was the site of the premier military radiological laboratory in the United States during the post–World War II era. The Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory used over 100 radionuclides. Shipyard environmental studies document a vast array of toxic chemical contaminants, including heavy metals like arsenic, mercury, manganese, lead, and the asbestos that contributed to my father’s premature death. Moreover, studies confirm the presence of petroleum products, pesticides and numerous airborne contaminants and toxic gases.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The Wizard of Oz

Two people aptly personify the traits of pathological narcissism, the fictitious Wizard of Oz and the very real former mayor of San Francisco, Willie Lewis Brown Jr.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders', people with Narcissistic Personality Disorder have a lifelong pattern of grandiosity in behavior and fantasy, and an unquenchable thirst for admiration. They are arrogant, self-important individuals—usually men—who commonly exaggerate their accomplishments to make themselves seem bigger than life. Narcissists fantasize about wild success and envy those who have achieved it. They choose friends who can help them get what they want. Their job performance may suffer due to interpersonal problems or be enhanced by their incessant drive for success. Despite their grandiose attitudes, narcissists have fragile self-esteem and fundamentally feel unworthy. Psychologists call this the “impaired real self” and its emergence is often provoked by minor insults called “narcissistic fractures.” Even during times of great personal success they may feel undeserving. As sensitive as they are, they may have little authentic understanding for the needs and feelings of others but may feign empathy in attempts to extract compliments or to further their belief that they are special.

Because they tend to be overly concerned with grooming and their youthful looks, they may become increasingly depressed with age. They may display cruelty, anger, dangerous rage or icy indifference in job settings and social situations where they are subjected to unflattering or unfavorable criticism.

State and local conflict of interest laws prohibit a public official from participating in public actions in which he has a private economic stake. One section of the state government code puts it this way: “No public official at any level of government shall make, participate in making, or in any way attempt to influence a governmental decision in which he knows or has reason to know he has a financial interest.”

The Hunters Point Naval Shipyard has been called “one of the most valuable pieces of soon-to-be-developed real estate in San Francisco.” While the site of massive environmental pollution, the former naval base offers impressive views of the Bay. The contract to develop the 500 acres of decommissioned land was awarded by the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency to Lennar Corporation of Miami, Florida. The redevelopment contract became politically controversial in 1998 because some of Mayor Brown’s close associates were hired as consultants by the companies competing for the contract, including trucking contractor Charlie Walker, lobbyist Billy Rutland, and local Democratic party chair Natalie Berg.

A San Francisco Weekly investigation revealed that Mayor Willie Brown Jr. was an investor in Live Oak Associates III and that this firm is a secondary investor in Whitney Oaks development project, a 1,000-acre golf course community north of Sacramento. A subsidiary of Lennar Corporation is paying the owners of Whitney Oaks for the right to build one section of the Whitney Oaks development.

The San Francisco Redevelopment Agency Commission, appointed by Mayor Willie L. Brown Jr. gave development rights for Hunters Point Naval Shipyard to a team led by Lennar Corporation, abandoning the recommendation of an outside consultant. The city retained Peat-Marwick to analyze three development proposals for the shipyard. The Lennar team, which is also developing Mare Island in Vallejo and had also won development rights for the Treasure Island development under Brown’s mayoral reign, won a unanimous vote by the seven-member commission, beating out Catellus Corporation and the Peat-Marwick consultants’ pick, Forest City Enterprises. They said Lennar had done a better job of mustering community support.

The Job Myth

On November 7, 2000, a declaration of policy was passed by 87% of San Francisco voters. Proposition P was formulated by a committee chaired by Hunters Point Shipyard Restoration Advisory Board community cochair Lynne Brown. Its original wording enshrined the mandatory requirement for community acceptance of environmental clean-up standards under the Federal Superfund law.

“The United States government should be held to the highest standards of accountability for its actions . . . the Bayview–Hunters Point community wants the Hunters Point Shipyard to be cleaned to a level that would enable the unrestricted use of the property—the highest standard for cleanup established by the United States Environmental Protection Agency.”

On November 2, 2000, Mayor Willie Brown and Secretary of the Navy Gordon England signed the HPS Memorandum of Agreement between the city and the navy. This action triggered an avalanche of debate among a vast array of community, government, and private interests regarding the health risks, economic benefits, and legal authority of the proposed phased cleanup and development of the shipyard.

In 1992 the Navy, state and federal regulators divided the Shipyard into six parcels to facilitate the environmental clean-up process. The parcels are sequenced A through F based on information available at that time and by the anticipated level of clean-up that would be required. Parcel A was touted as being the least environmentally challenged. Since that 1992 agreement extensive evidence has surfaced negating the navy’s claim that Parcel A meets standards for unrestricted residential development and reuse. Six radiation-impacted buildings are sited on the parcel and challenges have been filed to the original clean-up standards that led to the 1995 “no further action” determination of the Parcel A Record of Decision.

Most significant, two years after the August 2000 fire on the Parcel E industrial landfill, flammable and explosive methane gas was detected in concentrations exceeding 80% in air less than 100 feet from the Parcel A boundary with the extensively contaminated Parcel E.

Even more seriously contaminated than Parcel A is nearby Parcel B, where a former submarine base was found in a 1992 navy investigation to harbor soils that emitted gamma radiation more than 1.5 times greater than background. On analysis these soils were found to contain elevated levels of the radionuclide radium. This region of Parcel B has been designated for mixed use and community development under Lennar’s HPS Phase I Development Plan. It has been preposterously proposed as the future site for homes, “health care services,” and artist studios in the Environmental Impact Report surreptitiously generated by the Planning Department in November 2003, and adopted by the Redevelopment Commission as a “negative declaration” in April 2004.

A Civil Grand Jury investigation of the Hunters Point Shipyard was conducted and its findings and recommendations were issued in a 2001 report. Perhaps its most astute finding centered on the need for immediate implementation of Redevelopment Agency, navy, and city contract policies and programs that prioritize training and hiring in shipyard clean-up and development agreements.

Vehement dissatisfaction was expressed by community residents with regard to the passionless, visionless, directionless leadership and oversight of District 10 supervisor Sophie Maxwell. The most legitimate concerns focused on Maxwell’s blatant and negligent disregard for shipyard remediation and pressing health and safety concerns. She has paid little attention to measures that would create immediate job opportunities in the shipyard clean-up process.

The public has demanded that HPS remediation and development transaction agreements with the city and the Redevelopment Agency incorporate equal opportunity programs, nondiscrimination contracts, prevailing wage, minimum compensation programs, health care accountability, and the city’s First Source Hiring Program. According to the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency, “the HPS Conveyance Agreement requires to the maximum extent allowed under federal law that the Navy use its best efforts to give preference in contracts for remediation of the Shipyard to locally owned and minority- and woman-owned businesses in the Shipyard vicinity.”

In reality these goals were never met. A navy-sponsored economic development workshop was held in March 2004. A navy representative provided a dismal economic report. In fiscal year 2003, the navy spent $38 million on the shipyard and $700,000 locally. In 2004 the navy will spend $28 million on the shipyard, $2.5 million to local truckers and $144,000 to local businesses. In 2004 only twenty-eight local hires were made. In 2003 only thirty-nine local hires were made. Contrast this to the naval shipyard of the 1950’s where 8,500 civilians were employed, people like my father.

Newly elected Gavin Newsom perpetrated the shipyard development job myth and narcissistically credited himself with “breaking the log jam of the HPS Conveyance Agreement” in an article he authored in the local media. Peak homicide and unemployment rates among African American men in the southeast sector during the early months of 2004 further fueled the neighborhood’s willingness to be taken in by the Job Myth.

An analysis of the HPS Phase I Development by Arc Ecology planner and economist Eve Bach challenged the shipyard plan’s realization of job opportunities. In the years since the plan was first proposed by home-builder Lennar Corporation, light industrial and maritime development was phased out of the plan in favor of building additional housing units. In Bach’s words, “Although the project description observes that non-residential uses would be reduced by two thirds, it needs to be pointed out that this reduction would be achieved by eliminating all industrial and maritime development from Phase I. We believe that the city should be clear that in revisions to the Reuse Plan the Community’s job-creating strategy that prioritized light industrial development has almost completely vanished from Hunters Point Shipyard Phase I development.”

Under the proposed BVHP Redevelopment Plan Amendment, blighted portions of the BVHP Redevelopment Survey Area would be arbitrarily added to the Hunters Point (Hill) Redevelopment Project Area. The basis for the addition of these private homes and properties in the neighborhood surrounding the shipyard was the designation of the existence of deterioration or blight. Arbitrary “blight designations” like this have been used repeatedly by the Redevelopment Agency to remove specific populations. This same bureaucratic mechanism was used in the 1960s to target the African-American Fillmore district when it was at its peak of vibrancy as a West Coast Harlem. It was also used to remove the retired longshoremen and seamen from the area now known as Yerba Buena Gardens.

The San Francisco Redevelopment Agency and Mayor Gavin Newsom tout the BVHP Redevelopment Plan and the Shipyard Conveyance Agreement as the answer to joblessness and a boost to the local economic vitality of the southeast corridor. But the community is not “buying in” to the development process and the reality of forced relocation of multigenerational inhabitants. There is a growing belief among residents that the BVHP Redevelopment Plan is fundamentally a grand exercise in ethnic cleansing and in the words of SF Bayview publisher Willie Ratcliff, “negro removal.”

Breath of Fresh Air

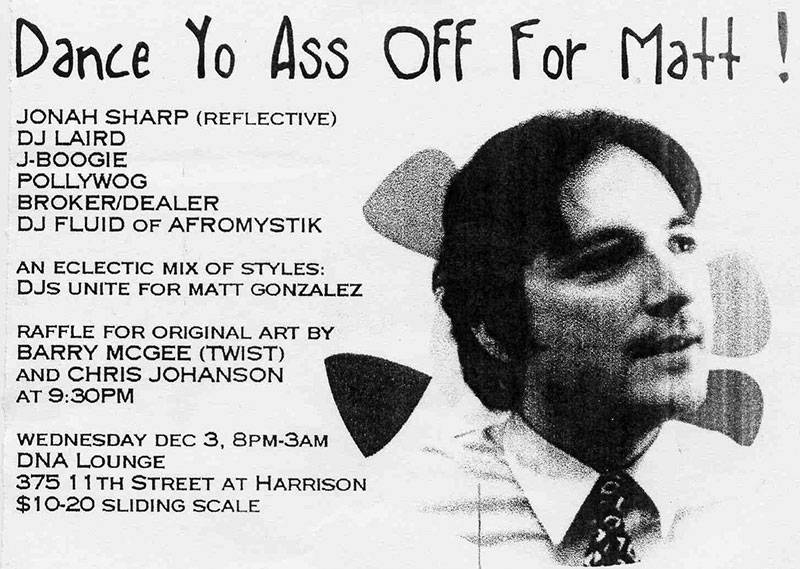

It was easy to fall in love with Supervisor Matt Gonzalez. He was a Green Party activist and potent political force whose message resonated harmoniously with my personal and political philosophies. He was a breath of fresh air. I had never met an elected official who was passionately concerned about the plight of animals, genuinely supported same-sex marriage, and was universally opposed to the death penalty. He was the Sir Lancelot of environmental protection. He was a respectful and enlightened man. Additionally, he was fiercely honest, humble, unpretentious, sensitive, and one of the most articulate and intelligent men I had ever met. His temperament was remarkable in the face of extremely stressful, long committee meetings.

It was easy to fall in love with mayoral candidate Matt Gonzalez. He was a man of ethnic and cultural heritage who always looked as if he needed a girlfriend to iron his suits, massage his back, prepare his lunch, and make sure he got plenty of exercise. He also enjoyed a good glass of wine.

The juggernaut of the 2003 Matt Gonzalez for Mayor campaign was launched in the basement of the Horseshoe Café one Saturday morning in August. I was there. It spread like wildfire throughout the Mission and Bayview–Hunters Point districts where two additional campaign offices were soon situated. Willie Ratcliff, publisher of the S.F. Bayview newspaper— the only paper that endorsed Matt in the primary race—donated the space for the Gonzalez for Mayor campaign office on Third Street and Palou.

Matt Gonzalez became the prodigal son and darling of the progressive left and galvanized a ragtag army of left-wing enthusiasts, many of whom had been pushed to the sidelines of San Francisco politics for decades. Another battalion of troops emerged from the freshly inducted new generation of young political thinkers and idealists who saw Gonzalez as the champion of leadership for the new millennium.

The Gonzalez for Mayor campaign took on a religious fervor and with every media attack or political slight his core group of apostles broadened. The Gonzalez for Mayor campaign was fueled by a People of Color coalition. Early on, the campaign drafted an Environmental Justice platform that drew mainstream media attention to issues in the Bayview, including the closure of the Hunters Point Power Plant, the clean-up of the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard and the need for clean, alternative, renewable energy sources including Gonzalez’s own proposal for tidal energy.

When Matt Gonzalez lost the mayor’s race and announced his decision not to seek a second term as supervisor it was as if the circus had left town without us. Left behind were the colorful remnants of a political fairground that once promised to bring redress to a host of political, social, ecological, and economic injustices we have endured under the arrogant machine of Democratic politics in San Francisco.

An avalanche of disasters hit Bayview–Hunters Point in the months following the corrupt inauguration of Mayor Gavin Newsom. The homicide rate reached a zenith. Newsom announced plans to site three additional peaker plants in Potrero Hill, and the Hunters Point Power Plant was granted a five-year reprieve for continued operations. Newsom announced the signing of the Conveyance Agreement to transfer the heavily polluted Hunters Point Shipyard for residential development. Using eminent domain, the Redevelopment Agency threatened to bulldoze the private homes and businesses of the dwindling and endangered African American community’s final political stronghold in San Francisco.

The community fought back. Legions of attorneys showed up at community meetings to volunteer time and consultations. The submissive District 10 supervisor faced two recall efforts. The Project Area Committee members for the Bayview–Hunters Point Redevelopment Agency were served with subpoenas for recall. The Conveyance Agreement and the shipyard transfer were held up by threats of legal action. The siting of the new peaker plants as well as the continued operation of the polluting Hunters Point Power Plant were met with fierce political opposition and legal challenge.

The fight continues but the elevator door is closing on the neighborhood I grew up in and on the friends and family and people I love. I am left with the saying from the stress and frantic hurry of my surgical internship, “the best way to stop a closing elevator is to put your head in it!”

published originally in The Political Edge ed. Chris Carlsson (City Lights Foundation: 2004)