City Workers Strike of 1976

Historical Essay

by Nancy Snyder, 2024

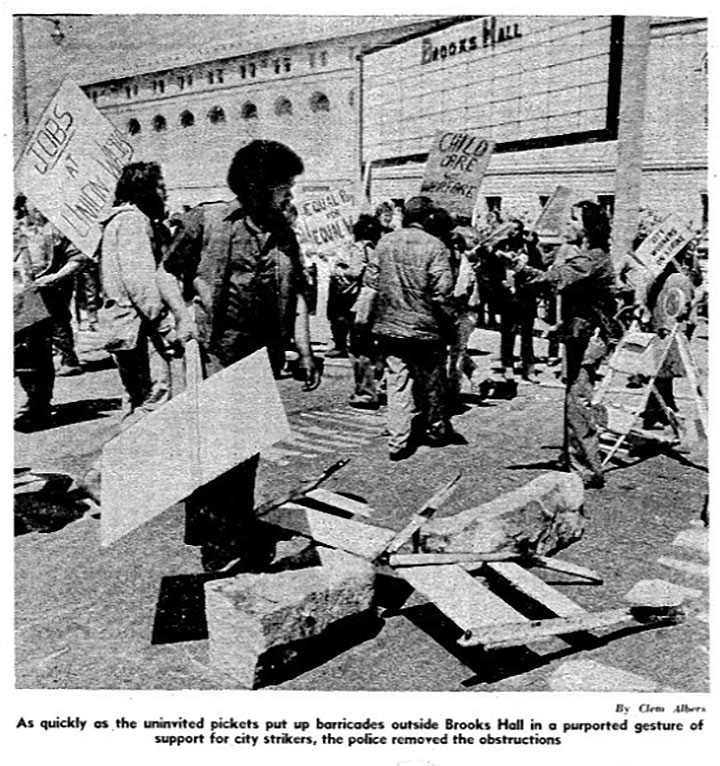

Photo by Clem Albers, San Francisco Chronicle

Mayor Joseph Alioto, who served as San Francisco Mayor from 1968-1976, was determined that all strikes be settled quickly. Therefore, when the police and fire departments went on strike in the summer of 1975, Mayor Alioto was able to utilize an obscure section of the City Charter and imposed his own settlement on the striking police and firefighters. Mayor Alioto’s move did not sit well with the other elected officials and City management—who clung to the belief that City workers should not be able to strike (an angry conviction that many wanted codified into law).

In the fall of 1975, despite the economic precariousness of San Francisco, the Board of Supervisors deemed it wise to place a measure on the November ballot that would lay the foundation for the municipal workers’ strike the next year.

The pay parity formula, which for decades set municipal employees’ wages under a public negotiator, was to be changed. Now the Board of Supervisors would determine their wages and working conditions.

State Senator George Moscone was elected Mayor at the end of 1975 with significant support from labor. However, a loud and proud conservative from the west side of San Francisco, Quentin Kopp, received the most votes among the Supervisors and thus became the President of the Board of Supervisors. His vote total was slightly greater than the new Mayor’s, a fact that Kopp continually reminded the Mayor privately and the public via the compliant San Francisco Chronicle.

During the winter of 1976, the questions of whether the crafts workers would stage a walkout lingered over the Labor Council. On March 22, a rally was called by the San Francisco Labor Council to strengthen labor’s resolve to walk off the job on April 1. Unless there was some movement forthcoming from the City to avert a 10% pay cut, the San Francisco municipal crafts workers would be walking off the job. There were many fiery and rousing speeches that day, making every unionist feel empowered to face the City’s onslaught of pay cuts and cutbacks as one union.

That would change a few days later when the Service Employees International Union would meet with their membership three days after the rally. In the 1970s, the Service Employees International Union represented the blue-collar workers of San Francisco. SEIU was primarily comprised of janitors and hospital porters, laundry workers and cashiers, clerks and telephone operators. The SEIU citywide locals included Local 400, Local 250, Local 66A and Local 535. They were called together for a meeting run by President Joan Dillon and by Vince Courtney, Acting Executive Secretary the SEIU citywide locals, where they were presented a contract given to them by the City’s management. The contract was a sweetheart of a deal; there were raises of 7%–11% and, to the members’ surprise, a no-strike clause. This all-important no-strike clause included the provision that would terminate any City employee (after a hearing) who supported any strike against the City. The SEIU leadership reassured their understandably angry members that if the remaining City unions were unable to settle, this contract would be null and void, and a new contract would be open for negotiation.

At the Labor Council, before the walkout set for April 1, head of the Plumbers Union, Larry Mazzola, was emphatic when he informed the SEIU reps, “We don’t want your people to go out.”

In the San Francisco Labor Council of the 1970s, Mazzola’s word, formally given or not, was unquestionably followed by the rest of the Labor Council. The Building Trades Council held the most leverage within the Labor Council, and the prospect of the craft workers receiving a more generous settlement if the SEIU locals did not strike, was the motive behind Mazzola’s actions.

The Board of Supervisors appeared to be taunting the craft workers to go on strike. On March 30th, the Supervisors voted to reduce their pay by ten percent.

On April 1, the first day of the strike, there was a major problem with the toilets and the plumbing at the San Francisco International Airport along with a lack of heat. 1,900 city employees had walked off their jobs.

As expected, the strategy of misinforming the San Francisco public—which had actually been in place for years—took a nastier turn after the crafts workers walked off their jobs.

The Supervisors expressed the most anti-union sentiment ever uttered in San Francisco history. They counted on a public fed up with city workers going on strike. This would be the third public employee strike in four years (the City’s nurses had gone on strike in 1972 and in the summer of 1975, the police and fire had walked off the job.)

The San Francisco Chamber of Commerce insisted on the layoff of City workers and the diminishment of City services instead of supporting new business taxes to bolster the City budget.

Board of Supervisors President Kopp took the lead as spokesperson for the Board of Supervisors during the strike. He reiterated the common talking points (“union members receive too much pay from the good people of San Francisco”; “San Francisco is not going to model themselves after New York”) and reveled in his new capacity as the righteous angry conservative bringing the truth to San Francisco residents. Board of Supervisors President Kopp loudly ridiculed the prospect that the strike, with only the crafts workers involved, would be successful. It was up to the citizens of San Francisco to quash the power of labor by saying “no” to their demands.

“Labor’s days of running San Francisco is over,” declared Kopp. “It’s even okay to criticize labor leaders now,” he crowed.

On the second day of the strike, Mayor Moscone moved into his office at City Hall and announced he would remain there for the duration of the walkout. From his temporary home at City Hall (that operated without hot water or heat), Mayor Moscone talked with the San Francisco Chronicle. The Mayor was confident that the San Francisco public supported his stance against the walkout. The Mayor referenced the hundreds of letters and phone calls from the City’s citizens who were supporting him in his decision not to capitulate to the strikers.

Mayor Moscone encouraged San Franciscans to essentially ignore the strike: the negotiators for the City and negotiators for the unions were meeting at that very moment to end this inconvenience of a walkout.

The scope of the craft workers’ walkout on the City was tremendous. “And that meant all the people who worked landscaping, it meant the plumbers at the airport, at Golden Gate Park, at the Academy of Sciences, it meant the electricians at every place. It meant the Hetch Hetchy water system with all of its employees who were part of one craft or another,” stated Supervisor Kopp.

The craft workers walkout was not just a minor inconvenience that could be bypassed, but an organized challenge put forth by San Francisco’s municipal workforce over how the City was going to determine wages and working hours for their essential workers.

The second day of the strike was the first day that San Francisco’s MUNI public transit system’s workers decided to stop running the City’s buses in support of the craft workers’ walkout.

“And then the MUNI Railway employees went on strike as a show of loyalty and devotion to their labor brethren and sisters, although there weren’t many sisters in 1976,” sniped Supervisor Kopp.

The 750,000 San Francisco residents were finding alternative modes of transportation while the streets grew more crowded. The springtime tourists still flocked to the City—the only deterrent to their fun times being the loss of a cable car ride.

When the strike entered its second week, twenty-five fire hydrants were vandalized, causing a temporary flooding of some of San Francisco’s streets. Also during the strike’s second week performances from the San Francisco Symphony were canceled for the duration of the walkout. Mayor Moscone delivered the bad news that the opening day of the San Francisco Giants baseball team appeared “bleak” and did not offer any rescheduling for the City’s diehard baseball fans.

The yellow school bus drivers’ had voiced their opposition to crossing a picket line set up by city workers. Similar picket lines had kept the MUNI bus service idle from the onset of the strike.

The Yellow Cab Company, the most prominent cab service in San Francisco that operated 500 of the 800 taxis in the City, came to a standstill. At the beginning of the walkout, Yellow Cab was served with a writ of attachment ordering the taxis not to operate, stemming from the long-standing debts Yellow Cab had incurred to the Teamsters Union. However, the outstanding debts were soon settled by a mediator and the Yellow Cabs reappeared on the San Francisco streets.

By the end of the second week of the walkout, Mayor Moscone made the same announcement he made on the second day of the walkout: the City and the unions would not stop negotiating until the dispute was settled.

A tense anxiety settled on San Francisco: the walkout was now approaching its third week, and labor and management remained intractable—there was no resolution in sight.

By the beginning of the third week of the strike, John Crowley, the head of the San Francisco Labor Council, announced that a vote for a general strike covering the entire workforce of San Francisco would be forthcoming. The Labor Council’s strike vote passed, but there was no further action by the Labor Council to actually prepare for a general strike.

Mayor Moscone claimed that the unions were not serious about a general strike. Mayor Moscone tried to convince the public that the unions wanted the San Francisco public to react in fear and loathing at such a suggestion. Mayor Moscone assured the public that if there was a citywide walkout, the City had plans to immediately quash it.

“It was a tough time for George Moscone,” Supervisor Kopp stated. “He was indebted politically to labor.”

On April 13th a court order stated that public workers did not have the right to strike and ruled the strike illegal. It was ignored by the strikers. The pickets remained outside of some of the city buildings; services were diminishing.

The latest wage offer made from the city, which was not that much different than the 10 percent wage cut, was rejected by the craft workers. About twenty-five percent of San Francisco’s 18,000 public employees honored the picket lines of the 1,900 striking craft workers.

By this time, residents of San Francisco were angry and divided regarding the 1,900 craft workers walking off their jobs. The inflationary costs of running city government along with the strike less than a year ago by the city’s police and fire departments, probably soured voters to the needs of their municipal workers. Their own basic economic needs were becoming harder to meet with no relief from the inflationary prices in sight.

Perhaps the craft workers had overestimated their strength at this given point in time given the relentlessly bad economy. Like the rest of the country, San Francisco in the mid-1970s was experiencing an inflation rate that had tripled from what it had been a decade before. Wages did not keep up with inflation. The impossible task of getting gas in the car became a national nightmare during the oil embargo of 1974—by 1976, things were still difficult, and gas was more expensive than ever.

Added to the economic hardships of San Franciscans was the property-tax assessment that was due to rise in 1976.

To understand the economic battles of the various craft workers, the San Francisco Chronicle did one good article portraying city cement mason 32-year-old Terry Webster who was interviewed walking a picket line outside a downtown city-owned building. The pay settlement offered by the city would cut his pay by $4,400 from the $22,000 he had expected to earn. Webster also has to pay the new property tax assessment.

One thing was certain, the San Francisco public did not want to pay a penny more for taxes. Gerald Crowley, President of the San Francisco Police Officers Association stated the obvious, “This is all a master plan to break the unions.” And, considering the influential weight downtown business held over the Board of Supervisors, it appeared that Gerald Crowley, influential voice within the Labor Council, was correct.

The persistent approach of the Board of Supervisors President Kopp before and after the 1976 strike was to list the salaries—which he wildly inflated to drive his rhetoric into the minds of the City’s population—of the overpaid and pampered City employees.

The end of the second week of the walkout revealed the blowback for San Francisco’s students: as a result of the MUNI walkout in support of the craft workers, the school buses stopped picking up San Francisco’s schoolchildren. Over half of the City’s students would not be picked up for school. By the end of the strike, there was a 400 percent drop in attendance at the City’s junior and senior high schools; 15,000 elementary school students were stranded and couldn’t attend school.

Unlike the two previous city strikes that were settled quickly, the 1976 craftworkers strike had no end in sight.

When the strike entered its third week, it was obvious to anybody working closely with the negotiating teams that they were near an impasse and needed to make the decision to form a committee to determine the facts behind the potential deadlock between labor and their city employers. Fact-finding committees are utilized to analyze a conflict between two parties and then produce a substantive report to resolve the conflict. The fact-finders are impartial experts in their field, and need to be approval by both parties to be seated on the committee.

The fact-finding committee for this deliberation consisted of five representatives chosen by the Board of Supervisors and five chosen by labor representatives. Mayor Moscone was chosen as the eleventh member of the fact-finding committee: Board of Supervisors President Kopp convinced his colleagues that the critical tie-breaking eleventh member to be an elected official who would face reelection. Kopp was emphatic that should Mayor Moscone run for re-election, he would have to face the voters regarding the cost of the strike. The fact-finding committee began their work as the public grew hostile to the union’s positions.

During the walkout, the Board of Supervisors and their downtown big business allies, had been busy crafting two ballot propositions to go before the San Francisco voters for the November election of 1976. The Board of Supervisors were developing a few prospective ballot measures that were intended as pure retribution for the MUNI workers. The proposed ballot measure would follow the same pattern as the craft workers: their past pay parity formula would be wiped out and MUNI’s future wages and benefits would be determined by the Board of Supervisors. Both ballot measures were focused on punishing municipal strikers. Proposition E called for the immediate dismissal of any city worker who “instigates, participates in, or affords leadership to a strike or engages in any picketing activity in furtherance of such a strike” against the City and County of San Francisco. Proposition K called for the ten percent cut in the craft workers’ salaries to be codified into the City Charter. By placing the wages and hours of the craft workers into the City Charter, it would need a two-thirds vote of the people of San Francisco to be removed from the Charter. Business interests and the Board of Supervisors were certain that their transitory advantage over the unions could be enshrined forever within the city’s arcane and voluminous Charter.

It was the fact-finding committee that settled the strike. At 2am on Sunday morning, May 8, the 39-day strike carried out by 1,900 municipal craft workers ended when the City’s Board of Supervisors voted to approve a back-to-work agreement accepted earlier by the union’s leadership. The agreement, which would become final when put to a vote of the union’s full membership, called for the return to work for all city workers at their current pay and without retribution. In exchange, the city agreed to remove the severe and punitive ballot measures E and K from the June 1976 ballot.

That Sunday, pickets were removed from the San Francisco Zoo and the San Francisco airport. The city’s workers began to repair the machinery and clean their facilities that had gone without maintenance for six weeks by the mechanics, carpenters, gardeners, laborers, plumbers and other blue-collar city workers. In the end, the crafts received a modest raise.

“The City is back on its feet,” declared Mayor Moscone.

After three public employee strikes in the 1970s happening within four years, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors had become unnerved. Forty-eight years ago, the Board of Supervisors could come up with no other plan than a no-strike clause to solve their employment problems. Nearly a half century after the no-strike clause was imposed on the San Francisco employees, it was found to be unconstitutional and was null and void. For the first time in forty-eight years, city employees would now be able to leverage their position in contract negotiations with a potential strike.

Local 1021, the SEIU union that represents the 16,000 San Francisco city workers in 2024, organized its members to avoid a strike and build a contract that would serve the members and serve the needs of San Francisco. The communication from the negotiating teams to the members worked efficiently; in March, there was a “strike school” attended by 1,600 SEIU members that informed members of how to plan and prepare for a strike—should it happen.

By April 12, 2024, the threat of a citywide strike was over: the 16,000 San Francisco city workers represented by SEIU Local 1021 reached a very favorable contract agreement. The largest bargaining unit of SEIU, the “classified” SEIU workers that represents most of the City workers in numerous departments, gained substantial improvements to contract language to mitigate the use of contracting out city services; a $25 hour minimum wage for all city workers; a 13% cost-of-living adjustment to cover the three-year span of the contract; and provisions to strengthen retention, recruitment and safer working conditions. The contract passed with 91% SEIU approval.

A few weeks later, the San Francisco nurses ratified their contract with 86% of union nurses voting yes. Safety issues stemming from understaffing the public health clinics and General Hospital were one of the biggest issues facing the nurses, and provisions attempting to rectify the situation were put in place.

In a City that is now home to dozens of arrogant, self-important tech billionaires, it is satisfying to witness how San Francisco is still, in 2024, a strong union town.