Experiencing the 1906 Earthquake

"I was there..."

by Doris Bepler Sharp, 1986, with contributions from Eva Knowles, 2024

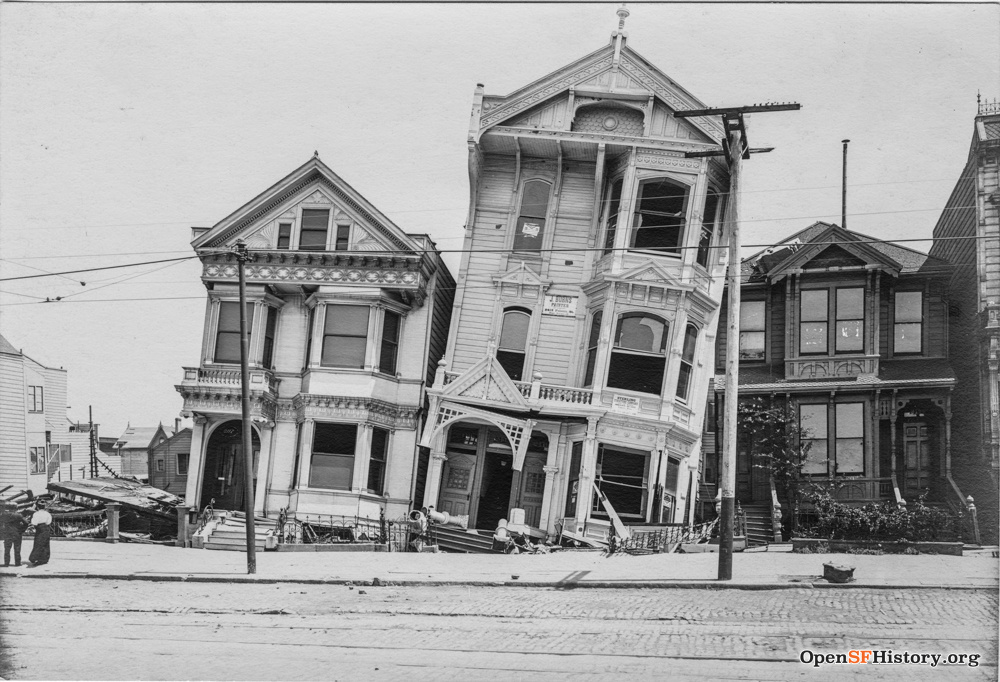

Tilted houses on South Van Ness near 17th Street.

Photo: OpenSFHistory / wnp27.1384

| Doris Bepler Sharp tells the story of her experience of the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake, including the quake itself; her family’s escape to the East Bay as fires swept across the city; first views of the devastated landscape left in their wake; and the problems faced within refugee camps nearby to her home. |

Doris Bepler Sharp was ten years old when the San Francisco Earthquake struck in 1906. She and her family—her parents and five sisters—lived at 60 Portola Street, (now Potomac Street) running into Duboce Park. She self-published a narrative of the earthquake and its aftermath in 1986 when she was in her nineties. Excerpts from this narrative offer an evocative picture of what it was like to live through this historical event.

Just after 5:00 am on April 18, 1906, San Francisco began to shake. The 7.9-magnitude earthquake, whose center is now known to have been offshore of the City, could be felt all the way in Oregon to the north and Los Angeles to the south. The quake lasted less than a minute, but to those like this young woman experiencing it, it was perceived as nothing less than Armageddon.

It was the end of the world. I knew it even before I opened my eyes. The awful rumbling, the violent shaking, these were all foretold in our Children’s Bible Stories. My eyes confirmed my fears. They saw my familiar bedroom, but now it was a room gone mad. The gas jet hanging from the center of the ceiling with its glass globe was swinging frantically. The heavy gilt framed portrait of my mother hanging beside my bed was crazily gyrating, leaping from the wall, twisting viciously on its wires. I crouched on my pillow as far as possible from that threat dangling over me. I kept one wary eye on it as I prayed, “Dear God, if this is the end of the world please take me to Heaven.”

Smoke from Buena Vista Park, a few blocks away from Duboce Park.

Photo: OpenSFHistory / wnp27.0344

Some became homeless instantaneously; San Francisco’s unreinforced buildings and densely-packed wooden Victorians were not equipped to handle such an impact. Those whose homes and businesses fared better found themselves without water or electricity. Furthermore, the threat of fires sweeping across the city quickly dashed any sense of security.

Today we saw nothing but a mass of black smoke rising into the flawless blue sky. “The city is on fire,” Aunt Anita told us simply. The rest of that warm sunny day we children spent in the Park. From there we could see that ominous cloud of grey smoke billowing into the April sky. Like the Genii, I thought, in the story of the Great Horned Spoon that Father read to us from the Saint Nicholas Magazine. We all had a feeling of uneasiness and so we sat close together on the grass and pulled Father's traveling robe over our heads. Under this we sang Up, Up in the Sky Where the Little Birds Fly, My Country 'Tis of Thee, Onward Christian Soldiers. From time to time one of us stuck her head out from under the rug hoping that the smoke clouds would have disappeared. But no, each time the black Genii seemed nearer and nearer.

View of the ruins from Nob Hill, including the Beplers’ route down Van Ness to Fort Mason.

Photo: OpenSFHistory / wnp28.080

Many San Francisco residents fled the fire-ravaged eastern side of the city for the north and west. Refugees could find food and shelter in Golden Gate Park and the Presidio in established Army camps, and many makeshift camps popped up in other parks and among the ruins. Some, like the Bepler family, chose to flee the City altogether until it was deemed safe to return, heading across the Bay via barge to Marin, Oakland and Berkeley. This mass exodus towards the water was not without chaos:

Word passed through the crowds that fire fighters were trying to stop the conflagration by blowing up the buildings on the east side of this wide avenue. Turning north on Van Ness Avenue, we needed no urging to hasten on. The tempo of the crowd became faster and faster as we heard blasts to our rear. Poor Mother and Father were desperately trying to keep us together so that we would not be lost in the ever thickening crowd. We no longer walked on the sidewalks, but overflowed into the street interfering with the few horse drawn vehicles. As we approached the pier we were hemmed in tighter and tighter as the road narrowed toward a gateway. We saw a barge at the end of the wharf, and, relieved, we pressed forward as fast as the crush permitted. We stumbled toward the escape that was just a few feet away. But as we neared the barge a barrier was thrown across our path, and there before our eyes we saw the barge move out into the bay. Were we to be left in this burning city?

Refugees leaving Presidio landing.

Photo: San Francisco Historical Photograph Collection / AAC-3670

The Bepler family sought shelter in the homes of friends and family living in the East Bay, searching by streetcar and on foot. They spent a period with friends of the children’s grandmother in Berkeley, where they observed others displaced from San Francisco.

If we were lucky we might see refugees alighting from the train. We could tell that they were refugees because they always carried many bundles, battered suitcases tied with rope, perhaps a plant, perhaps a birdcage with parrot or canary. But most commonly they were laden with pillowcases stuffed with all sorts of knobby objects.

San Francisco fires from the East Bay.

Photo: OpenSFHistory / wnp37.01226

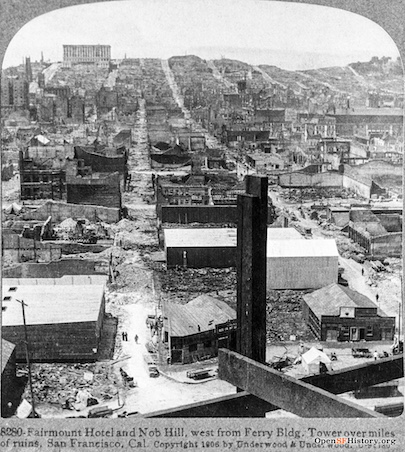

View of the ruins from the Ferry Building, 1906.

Photo: OpenSFHistory / wnp37.01073

When refugees like the Beplers returned home to San Francisco, they were unprepared for the devastation that lay before them. The fires ultimately destroyed almost 500 city blocks, leaving hundreds of thousands of people homeless.

A scene of desolation lay before us as we emerged from the Ferry Building. No structures, only skeletons of what used to be buildings. Below the level of the streets we looked into basements littered with heaps of bricks and stones, twisted steel beams, stumps of chimneys and walls. Small wooden and canvas shacks were already rising here and there hiding some of the rubble. We girls stood in a huddle wondering how we would ever reach home. We saw that the tracks for the horse drawn streetcars that we usually rode were too hopelessly mangled to be of any use. We were in a nightmarish and unfamiliar land. … The streets and the air were thick with grey dust. Often I sank into holes to the tops of my high laced shoes. My eyes smarted from the whirls of grit that each step stirred up, and when a vehicle passed we could hardly see our way through the clouds of fine powdery dust and ashes. When I dared lift my eyes from the uncertain road I darted frightened glances to right or left. There was nothing familiar––no houses, no shops, on cheerful billboards whose words I was learning to read.

Earthquake survivors cooking outside on Shotwell Street.

Photo: OpenSFHistory / wnp15.1070

The family and their neighbors set to work repairing their homes. The pipes had been repaired but the chimneys were not yet deemed safe, so cooking was done outside, resulting in a neighborhood camaraderie.

I remember the street with a cooking arrangement before almost every dwelling. Sometimes one saw only a grate set on bricks, sometimes a potbellied stove from a basement laundry. We girls were sure that we had the neatest and largest kitchen camp. Mother and the neighbors visited one another, peering into fragrant pots, discussing menus and recipes, and tasting little samples of food.

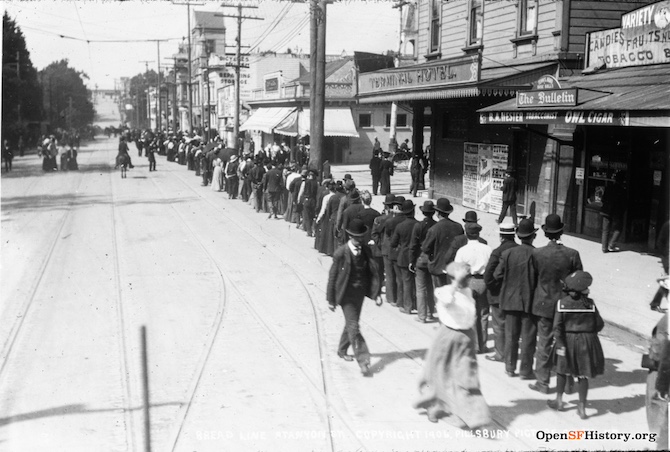

Bread line at Stanyan and Haight.

Photo: OpenSFHistory / wnp59.00115

Some areas of the city had begun to settle somewhat by the end of the summer. The Bepler family was able to cook inside, and schools were to reopen that August. However, others displaced by the earthquake and fires who had lost their homes and material possessions altogether remained in refugee camps, including in Duboce Park. Various services were provided for the refugees, including bread lines in the park.

A call went out for clothing, especially for school children. I urged on Mother some of my dresses that I disliked for the collection. I was not completely successful. Louise and I carried the bundles to our Hearst Grammar School just two blocks from our home. Imagine my sensations when on the first day of school I spotted one of my discarded dresses on a girl in the schoolyard. I felt sorry for her. She had to wear that old green dress that wouldn't fasten properly at the back.

Refugee camp in Duboce Park, looking northward toward homes on Potomac Avenue.

Photo: OpenSFHistory / wnp15.1725

Refugees also suffered from—and were blamed for the spread of—various diseases and ailments. Soon the rebuilding of physical infrastructure became just one concern among many for San Francisco families.

Mother heard of various health hazards, and so we were not allowed to walk through that part of the park where tents were still inhabited. We had to go the long way around to school. Even so, we did not escape some of the difficulties that were prevalent. Probably the most distressing was pinkeye, which infected all six of us. For weeks we could not open our eyes in the morning. Mother placed a saucer of boric acid solution by each bed. With eyelids stuck tight, we groped until we felt the wad of absorbent cotton next to the saucer, fumblingly dipped it into the solution, and washed off the hardened crust that glued our eyelashes. Another health problem: Alice came from school one day ominously scratching her scalp. Mother examined her hair carefully and found to her horror what she feared. Then began a daily torment for all of us. One by one we stood over a large white sheet of paper while Mother or Grandmother went through our hair with a fine toothed comb.

At the same time, the bubonic plague reappeared in San Francisco. Having first broken out in 1900, it had been centered in Chinatown and was contained by 1904. This reemergence, however, had no center; instead, cases broke out randomly throughout the city.

Newspapers carried alarming tales and precautions to take against the threatening plague. Dr. Blue, Surgeon General of the United States, came from Washington. Mother heard his report at a Parent Teacher Association meeting at our school. She added one of his suggestions to her already active anti-flea campaign. She bought a bottle of carbolic acid and with a medicine dropper squirted a little of the stuff on the back of our undershirts. The effect was instantaneous. The wet spots came against our skin and we all howled with the burning pain.

Amid these fears was the heavy yet exciting feeling of historical significance. Bepler Sharp describes a conversation she had with a U.S. Navy crew member that altered her outlook on the earthquake and her place in it.

“What wonderful people you are to have rebuilt most of your city in these last two years. I'm sure glad to have visited your brave city.” And so he led us to the gangway and bade us farewell. Now history was my favorite subject at school. But I felt sad that it was all so long ago and so far away. How I longed to live in historic times! But all the way home on the launch and on the streetcar I began wondering. If that nice sailor thought that what we had lived through was so important and so interesting, why perhaps I was actually living with the history of my city of San Francisco.