A Woman's View 19th Century San Francisco Women Photographers

Historical Essay

by Mary Brown, 1997

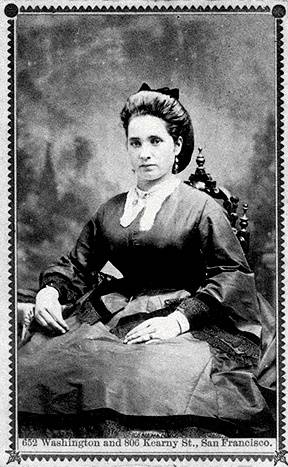

Carte-de-visite portrait (enameled card patent) of an unidentified woman, San Francisco, c. 1869-1870, by Julia A. French.

Photo: Peter Palmquist collection

In 1839 very little was happening in Yerba Buena, an unassuming Mexican town on the San Francisco Bay. It was mainly populated by cows, with a few ranchers, a grubby settlement of Yankee sailors and some unfortunate Ohlone Indians toiling away and dying off at the decrepit Mission Dolores. This same year, halfway across the globe, a most stunning discovery was announced. Frenchman Louis Daguerre had perfected his technique of combining a lethal concoction of silver nitrate and affixing it to copper plates to capture images. He named his invention the daguerreotype, the world's first form of photography.

This discovery was destined to have a profound effect on the lives of women living in the foggy, sandy hamlet soon to be re-named San Francisco. Photography became an emancipator of women on the western frontier—an exciting and viable alternative to the few work roles that were socially acceptable for the so-called weaker sex.

Women were involved with photography in SF almost since the first introduction of daguerreotypes, during the Gold Rush. They became an integral part of the trade, working as studio photographers, traveling photographers, proprietors, gallery owners, retouchers, colorists, photo-mounters, and near the end of the century they joined the swelling ranks of amateur art photographers. From 1850 to 1900 there were 77 working female photographers and 205 women earning a living in photography-related trades. An additional 52 women are documented as amateur or fine art photographers.

Women both shaped and were shaped by the advent of photography in 19th century San Francisco. The photographers described here are remarkable for their achievements, particularly so in light of the chauvinistic, male-dominated city in which they worked and lived. The women include the earliest pioneer daguerreotypist, an experimental X-ray photographer, a Chinese photographer in a divided city.

Pioneer Daguerreotypists

1850: The Gold Rush was in full swing and wild-eyed adventurers had transformed San Francisco from sleepy village, to a lawless, chaotic city of almost 35,000 dwellers. It was a city of tents, mud, and hastily slapped together wooden buildings teeming with immigrants, hope, greed, money and men. There were very few women and even fewer respectable ladies. In the midst of this turbulence, Mrs. Julia Shannon, the first known female photographer in all of California, made her appearance advertising in the January, 1850 issue of San Francisco Alta:

"Notice—Daguerreotypes taken by a Lady—Those wishing to have a good likeness are informed that they can have them taken in a very superior manner, and by a real live lady too, in Clay street, opposite the St. Francis Hotel, at a very moderate charge. Give her a call, gents."

Alongside the swarms of miners hibernating in SF for the winter, Julia Shannon joined the tiny ranks of San Francisco daguerreotypists, arriving just one year after the first male photographer Richard Carr. On his arrival in 1849 Richard recorded in his diary the exorbitant prices for common goods—boots for $16, blankets for $40, and also noted, "Yankee freedom is such that you can't get treated with civility at any price."

It seems that Julia was a jack of many trades: in later advertisements, along with daguerreotypy she also offered midwifery services. She was fairly successful and well off until the disastrous May 1851 fire that incinerated one-quarter of the town, burnt down the two houses (valued together at $7,000) she owned on Sacramento Street. Unfortunately, this is almost all that is known about Julia, as there is no further record of her after 1852, and none of her daguerreotypes are known to have survived.

It is possible that Julia was not the first woman photographer in San Francisco, since many photographers never advertised in newspapers, and only five percent of all known daguerreotype images identify the daguerreian. Also, many women worked in the family photography studio without ever receiving mention in advertisements or business directories.

In order to really appreciate what an accomplishment it was for Julia to have her own Daguerreian studio, its important to understand this early form of photography. For the first 50 years, photography was not the point and click affair that it can be today. It was a combination of science and art, two fields that were particularly unwelcoming towards women. It was difficult for anyone to master the early forms of photography: cameras were bulky and cumbersome; processing formulas were complex, dirty and exacting. Wet-plate negatives had to be coated with emulsion immediately before exposure and then developed directly afterwards in potentially lethal mercury solutions. It was hard-core, gritty work. Women in San Francisco were mastering photography in a struggle to make their own living at a time when corsets were still required clothing, years before the end of slavery, long before cars were invented and a full 70 years before women were allowed to vote.

There was very little artistic experimentation occurring in the West—in fact, amateur photographs were practically non-existent until the late 1880s. Photography was too expensive, too dirty, and too toxic to be a hobby: not many people were inclined to fiddle around with it in the name of fun. Most early San Francisco photography was straightforward, professional studio portraiture work. Studio space, in fact space in any building, was extremely scarce, and the early photographers needed large windows with bright sun exposure. Studio work was generally between the hours of 10am to 3pm, to take advantage of the best natural light. In many respects the portraits themselves are interchangeable. Daguerreotypes are notable for their uniformity: the sitter is almost always posed against a light background, from the waist up, gazing straight ahead. Yet each daguerreotype is a unique image. Unlike modern photography, which prints a positive picture from a negative, Daguerreotypy used no negative; the plate exposed in the camera is also the finished product.

Average exposures lasted 30 seconds. The sitter was admonished to stay absolutely motionless with his/her head squeezed into a head clamp (there are very few spontaneous grins in old photographs). If successful, the resulting image was protected by a layer of glass, and enclosed in a frame or velvet-lined leather case that opened and closed like a book. Holding a daguerreotype is the only way to truly appreciate the minute detail and mirror-like quality, and by tilting it to the side you can see the image laterally reverse from negative to positive. It was often referred to as the "mirror with a memory."

From the beginning, this new phenomenon had broad appeal among the working class and the wealthy. For the first time ever, even the poor were able to possess a likeness of themselves. As Susan Sontag noted, photography implied the capture of the largest possible number of subjects. Painting never had so imperial a scope.

Only one other woman besides Julia Shannon was listed in the 1850s, an unnamed photo colorist working for Freddy Coombs, (an early daguerreian turned eccentric, who became the social rival of the equally flamboyant Emperor Norton). She is mentioned in a November, 1850 advertisement in the Daily Herald:

"F. Coombs, Daguerrean, at Wells & Co.s new building, corner of Clay and Montgomery streets, has the pleasure to announce that he has secured an additional coloring Artist-- a young lady who has presided over the finishing department of the first Gallery of Boston several years. He hopes in the future to accommodate every applicant with a Picture which will bear comparison with the choicest..."

There were precious few ladies in the early years of San Francisco, clearly the presence of a woman photographer was a novelty. Women who worked were considered brazen and remarkable by some and completely reprehensible by others. Only a handful of women photographers were known to have worked in the entire state during the 1850s, but San Francisco, until well into the next century, was the hub of photographic activity in California.