Amanda Genung: San Francisco’s Own Pistol-Packing Pioneer Photographer

Historical Essay

by Sean William Nolan

Amanda Genung

On February 28, 1864, San Francisco’s second female photographer was in court, being granted a divorce from her husband of 25 years.

This notice in the Marysville Appeal brings up more questions than it answers. Putting aside the fact that Genung’s surname is misspelled (a common occurrence) and that it was Amanda who abandoned him, how could she be granted a divorce from a marriage of 25 years and simultaneously admit that she had been divorced four times in the interim? She would be admitting to bigamy, trigamy, or worse. This is one of several mysteries about her life, a life with more twists and turns than the intestines of a yak.

Amanda Genung was a square peg in the round hole of Victorian America. From a freethinking family in upstate New York, she traveled without a male escort through the Panamanian jungle. Once in California, she refused to accompany her husband when he decided to return east. She was a professional photographer at a time when all other photographers in the state were men. She worked in China for a year. She lived with two different men before marrying one of them, a man 17 years her junior. She may have been captured by pirates. She definitely had a Colt pistol.

When discussing photographers, I will refer to her as “Genung.” In the context of her family, I shall use “Amanda” to distinguish her from her first husband Oshea and her son Charley.

Although Genung’s career lasted over a decade, few surviving photographs are attributed to her, and none are signed. She was a photographer when the odds were against her. In the 1850s, only one in 50 photographers were women. In California, Genung was preceded only by Julia Shannon (circa 1812 - July 1854), a midwife who advertised as a daguerreotypist in two 1850 issues of San Francisco’s Daily Alta California. Julia Shannon lost two buildings on Sacramento Street in the Great Fire of 1851, which presumably ended her photographic career. Not until 1856, when Genung worked in Downieville, would California have another female photographer. Not until 1860, when Genung moved to San Francisco, could that city make the same claim.

Penn Yan

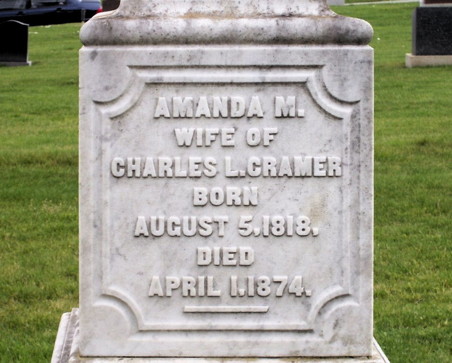

Amanda M. Baldwin was born on August 5, 1818 in Penn Yan, which lay in the midst of the “burned over district” of upstate New York, an area was so named for the fiery religious and reform movements which flourished there in the early 19th century. Two poles of religious opinion can conveniently be represented by two men in Amanda’s life—Dr. Alfred Baldwin and Oshea Genung. Baldwin, her uncle, was described as “a man of strict integrity, though noted for his disbelief in revealed religion.” Oshea Genung, Amanda’s future husband, was a religious tyrant who would quote Bible verse while whipping their son Charley.

Amanda and Oshea married in 1839; it was probably a shotgun wedding, as their only child Charles, or “Charley,” was born on July 22, 1839.

That same year, a French artist named Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre announced a hard-to-believe invention. His daguerreotype was the first photographic process, made on a highly polished silver plate. “I have heard that a man in France has invented a mirror which retains your image,” a young man announced to his father. “If you believe that, you are an even bigger fool than I imagined” was his father’s reply. Everywhere, the announcement of the daguerreotype was greeted with astonishment. Here were detailed drawings made without the hand of an artist. “Bridges and trees drew themselves” in Daguerre’s camera. Within a year or two, exposure times were short enough that portraits were practical and daguerreotype studios opened in major cities across across Europe and America.

In 1845 Amanda’s son Charley contracted whooping cough, weakening his lungs. This prompted the family to move several times in an attempt to find a healthier climate. In the fall of 1853, they headed to California.

There were three routes to choose from. Traveling overland in a covered wagon took about five months, with the risk of Indian attacks, accidents, and starvation along the way. The safest, but most expensive, route was by ship around Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America. The quickest route was to take the shortcut through Panama, but this exposed travelers to malaria and yellow fever as they crossed the jungle. Crossing the isthmus in 1853, before there was either a railroad or a canal, required a difficult eight-day trek by dugout canoe and mule. This is how Amanda and 14-year old Charley travelled while Oshea went overland.

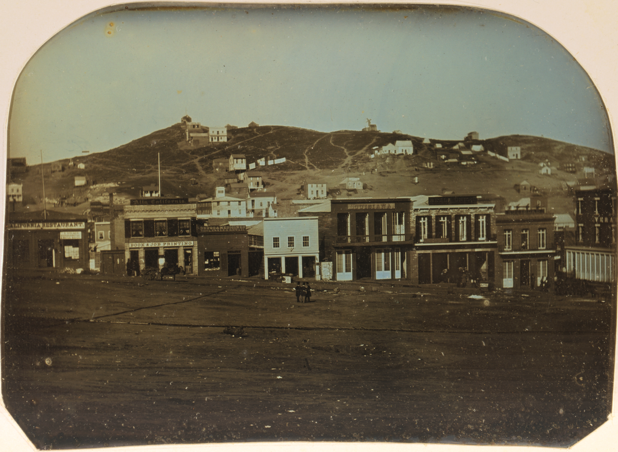

The city Amanda and Charley arrived at was new. Seven years prior, the settlement then named Yerba Buena boasted a population of only 250. On February 2, 1848, the city, as well as the entire Mexican Cession, became American territory. Within days, news leaked out about the discovery of gold at Sutter’s mill. The Gold Rush was on! The trickle of new settlers became a flood, and by 1850 the city had grown to 25,000. With local government unable to maintain order, a self-appointed Vigilante Committee enforced rough justice. By 1851 the ramshackle city had been nearly destroyed by fire seven times.

Portsmouth Square, 1851.

Courtesy Library of Congress

By 1853, when Amanda and Charley arrived, San Francisco was relatively civilized. The first fireproof building had been built and the Vigilante Committee was temporarily disbanded.

By the end of 1853, [San Francisco] had many hotels, public boarding and lodging houses, restaurants, bakeries, and public markets. There were also banks, insurance companies, public schools, churches, fire companies, lodges of benevolent societies. There was a chamber of commerce, a mercantile library association, a number of merchant, literary, professional, religious and social societies, a gas company, a water company. There were consuls from 27 foreign governments, twelve daily newspapers, six weeklies and two monthlies. There were theaters, a music hall for both concerts and other exhibitions, two racecourses and a gymnasium.

—John Rose Putnam, My Gold Rush Tales blog

When Oshea arrived in San Francisco, he was not similarly impressed:

“Goddamn it, who can live in this godforsaken hellhole!” Amanda recalled [him saying]. “He disliked everything, the frame structures, the canvas houses, the roisterers trampling the streets day and night. It was so unlike Penn Yan [New York]. 'Sodom and Gomorrah,' he'd say. Then he had a run-in with that gang of Australian toughs, the 'Sidney Ducks.' Everybody says they started the fires. And those ‘Hounds' who posed as patriots 'to hound all foreigners' turned out just as bad. They looted and murdered and burned. Oshea said the fires were the judgment of God. Sodom and Gomorrah … Babylon … God's judgment.”

Oshea and Amanda Genung

The Genungs found work on a ranch near Marysville. It was probably at Robert H. Vance’s Marysville studio where Oshea and Amanda Genung had their joint portrait taken. Oshea, in character, appears disapproving and obstinate. The bird-like Amanda engaged the camera more directly and appears ready to spring up or crack a smile. This is the only known photograph of Amanda but Oshea can be identified from a later Carte de Visite taken in Penn Yan, New York.

Having your picture taken in 1854 was not trivial. Nearly all photographs were taken indoors at professional portrait studios; there were no snapshots. Robert H. Vance was California’s predominant photographer; he owned a chain of studios under his name and hired “operators” to work them. Larger studios such as Vance’s main studio in San Francisco were run like an assembly line. Customers might be braced with a head clamp to ensure that they remained still during the 10-second exposure. After exposure, the plate would be developed over hot mercury. These photographs are black and white, so a colorist might touch up jewelry in the image with gold paint, add a color wash to clothing, or add blush to the lips and cheeks. Finally, the delicate daguerreotype plate would be matted, placed under glass and put in a leather case. Each picture might cost $5 ($100 today).

Lotta Crabtree

Amanda and Charley moved, without Oshea, to Grass Valley, California, in the Sierra Nevada foothills. There Charley had a milk route, where he would be followed by a young Lotta Crabtree, who would sing and dance as he made his rounds. Lotta was a child at the time, just beginning her career as an entertainer in the local theater. Years later in San Francisco, Lotta, who according to Charley was “wild about him”, would search out Charley and drag him to see a fortune teller before they began their separate journeys—he to Arizona and adventure, she to New York City and stardom. Lotta Crabtree (1847–1924) would become the highest paid American actress of her generation and a generous philanthropist.

Lotta's Fountain with its new coat of paint and the restored facade of the DeYoung Chronicle building behind, 2013.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

In 1875 she donated Lotta’s Fountain, which still stands at intersection of Geary, Market and Kearny Streets.

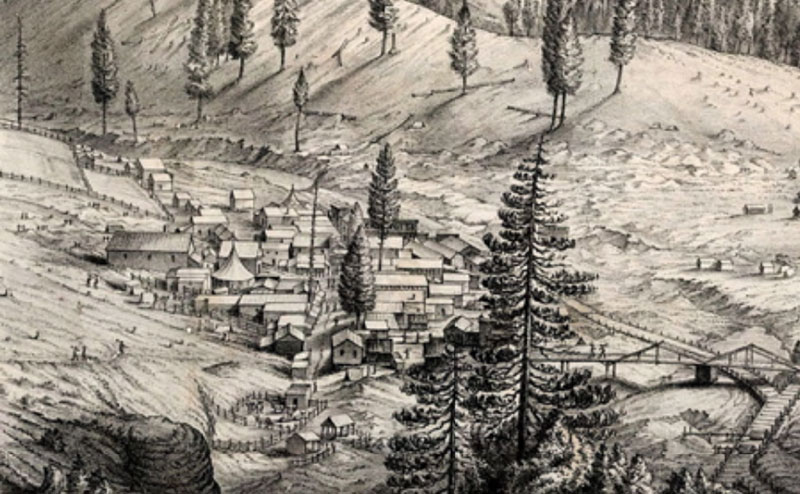

Amanda and Oshea Genung split up for good in 1855. When Oshea returned to New York, Amanda refused to follow and moved with Charley to the Gold Rush town of Downieville in the Sierra Nevada. Currently a town of only a few hundred people, Downieville was once one of the largest cities in California. Although Genung had been taught the art of daguerreotypy in Penn Yan, it was in Downieville that she began her career as a photographer. And it was in Downieville that she met Jane Cary. Soon they would be business partners.

Downieville, c. 1851.

courtesy Library of Congress

Jane

On September 23, 1857, the San Joaquin Republican reported:

Ambrotypes, photographs on glass, were a new invention which were easier, cheaper and safer to make than daguerreotypes. A more effusive description of their gallery, albeit with both names misspelled, appeared in November:

The sole extant photograph of Stockton from that era shows the intersection exactly one block west of their studio.

View of El Dorado Street and Levee Street, Stockton 1850s.

courtesy of Library of Congress

Sadly, their studio was short lived. Only thirteen weeks after opening, this advertisement appeared in the San Joaquin Republican on New Year‘s Day 1858:

Eight days earlier Genung’s partner Jane Cary had married. This photograph of the newlyweds was almost certainly taken by Genung, as their studio was in operation at the time:

San Francisco

In 1859 Genung was living in San Francisco, sharing Robert H. Vance’s house with the photographers Milton Miller, Charles Leander Weed, and possibly Vance himself. Miller, previously Vance’s “operator,” now worked for Weed, who had recently purchased one of Vance’s San Francisco studios. Late in 1859, Weed crossed the Pacific to open a studio in Hong Kong, an event which would soon bear important consequences for Miller, Amanda and her son Charley.

The 1860 San Francisco city directory listed Genung as a “daguerreian,” working at the southeast corner of Clay and Kearny. Charley claimed that she ran her own studio, but she was actually an operator for Clark and Smith at their fourth-floor gallery (all photo galleries were on the top floor because of the need for skylights). But she wouldn’t work there long.

The same year, Weed wrote from China, asking Miller to take over his Hong Kong studio. Amanda and Charley accompanied Miller to China, leaving San Francisco on the Alfred Hill at the end of May and arriving just before the final climactic battles of the Second Opium War.

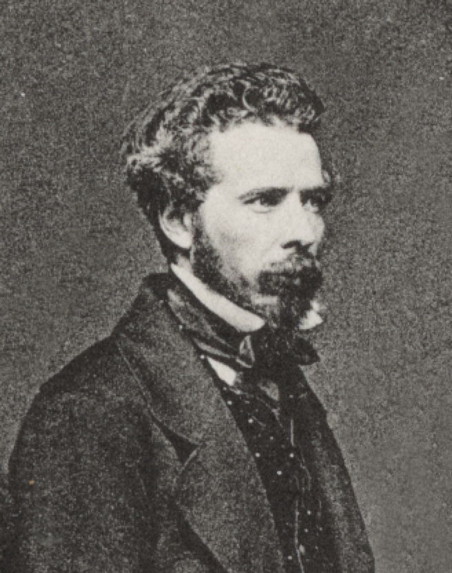

Milton Miller from A Camera in the Gold Rush.

Miller is best known for having taken “the most significant body of nineteenth-century Chinese official portraits.” Terry Bennett praises him highly in his History of Photography in China 1842–1860:

Milton Miller was arguably the best portrait photographer in nineteenth-century China… Miller’s genius is particularly evident when photographing Chinese people. He was clearly at ease in their presence, and they in his. This empathy with his subjects broke new ground and is evident in the way they are portrayed…. Later photographers occasionally produced portraits of equal merit, but never with Miller’s consistency.

Miller’s eleven famous portraits and group photographs, taken in Canton in 1861, include both court officials and middle-class families, with titles such as A Mandarin and his Wife, Portrait of a Young Chinese Man, The 1st Wife of a Tartar General, and A Mandarin and his Wife in Full Court Dress. 150 years later, Miller’s identification of his subjects was debunked by Professor Wu Hung, who noticed that the photographs featured a rotating cast of characters who swapped costumes and roles between the different tableaus.

It is most likely that Genung worked for Miller, as there are two ship manifests showing them traveling together in 1860 and 1861. In 1860 they traveled to Shanghai. The following year they were in Shanghai again on their way home from Nagasaki, where Miller had taken some of the earliest stereoscopic photographs of Japan.

Pirates

Amanda and Charley’s return to San Francisco is the most interesting and confusing episode of her Chinese sojourn. Charley’s Memoirs relate how he and Amanda returned to California in 1862, again on the Alfred Hill, when the ship was wrecked on the Pratas Shoals in the South China Sea and then encountered pirates. According to Charley, the crew and passengers were seized since Amanda had the only functioning gun onboard—her Colt pistol. A Chinese merchant, traveling on the Alfred Hill, negotiated a ransom and everyone was returned safely to Hong Kong. This unlikely story turns out to be true, although the incident actually happened in May of 1861:

Charley’s recounting conflicts with some of the known facts: that the ship was heading towards Hong Kong when it was wrecked, that it was the lifeboat rather than the ship which was attacked, and and that the incident took place in 1861. Most importantly, Amanda could not have been present. At the time she was either in Nagasaki or in Shanghai preparing to meet Miller upon his return. Possibly Charley, accompanied by Amanda’s Colt pistol, was on one of his trips to bring photographic supplies to Hong Kong.

Cramer

Amanda re-appears in the San Francisco city directory in 1863, listed as a widow. However, Oshea was still alive and kicking in Penn Yan; he would survive her by a decade. The following year she divorced Oshea, claiming abandonment, discreetly omitting the fact that it was she who had abandoned him. The reports of her divorce now initiated a propensity for misspelling her name in newspapers and city directories: Gunung, Gunning, Gening, and Geming. She continued to describe herself as a widow, using her ex-husband’s surname, even after publicly divorcing Oshea.

Self-portrait of Charles Lake Cramer (probably), 1870s.

from Collection of Jules Mertino

The following year Genung was living with the photographer Charles Lake Cramer at 239 Jessie Street. This was most likely a single-family dwelling, as no-one else in San Francisco was listed at that address. I believe the legal term for such an arrangement is “shacking up.” Cramer was a partner at the Bayley and Cramer studio in San Francisco. The following year Genung and Cramer opened their own studio—the California Photographic Galley. It was there that Genung took a post-wedding portrait of Charley.

Cramer took a photograph of Portsmouth Square, San Francisco, in the late 1860s. By coincidence, it appears to have been taken from the same building where Genung worked for Clark and Smith back in 1860. This is San Francisco as Genung would have seen it, precisely.

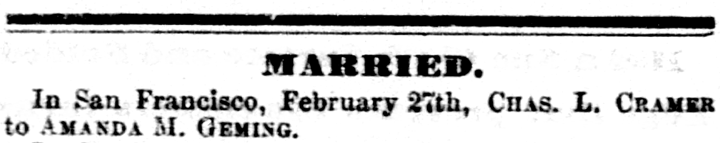

Genung’s last appearance in the city directories is in 1872. By the time the directory was published in March, Genung had married Cramer, 17 years her junior. As a fitting tribute to her obscurity, the newspapers would misspell her name one last time.

Genung, whose health been poor since her supposed three days in the Alfred Hill’s lifeboat, died on April 1, 1874 in San Francisco. Perhaps to atone for previous misspellings, her newspaper death notice knocked ten years off her age.

Within the Genung family, Amanda was remembered as a strong and independent woman. Outside of her family she was largely forgotten. One reference book, Pioneer Photographers of the Far West {italics}, devoted four sentences to her, noting her 1860 San Francisco studio address and quoting her 1857 Stockton Daily Argus {italics} advertisement. Amanda is mentioned briefly in Charley‘s unpublished memoirs and in his biography (written his grandson), but neither source had more than a sentence on her career as a photographer. In 2016 I acquired three early photographs of, or by, Genung and her partner Jane Cary, initiating eight years of sporadic research. This led to my article “Mrs. Genung and Miss Cary, artists of established merit {italics},” in the 2023 Daguerreian Annual (Daguerreian Society, 2024, pp. 248-264), which became the basis of this article. The article, with complete citations, is available here.

Acknowledgments

I could not have done this on my own. I owe thanks to many people for their time, research, and expertise. Among them are Carole Howard, Jane’s great-great-granddaughter; Genung family members Alexis, April, Claudia, and Sharon Genung; Tom Schmidt of the Sharlot Hall Museum; Jennifer Craft-Hurst, daguerreotype collector and researcher; Richard Wood, daguerreotype collector and researcher; Gloria Jacobs, researcher, proofreader, and provider of moral support. Thanks to Carole Howard, Richard Wood, Jeffrey Kraus, the Library of Congress, the Getty Museum, and the Bancroft Library for generously allowing the reproduction of their photographs and prints. Last, but not least, thank you Terry Bennett, author of History of Photography in China, and John Rose Putnam My Gold Rush Tales blogger, for allowing me to use excerpts from your work.

About the Author

Sean William Nolan has been collecting early photographs for 50 years, a venture which combines his love of history and photography. He is the founder of the Society for the Repeal of the Second Law of Thermodynamics, which anybody can join by alphabetizing their spice rack, carrying a stone uphill, or writing a fugue. He is also the author of Fixed in Time (in print or free download), a guide to dating cased photographs based on their mats and cases.