1918 Flu in SF: A Closer Look

Historical Essay

by Arnold Woods, March, 2020

Reprinted from OpenSFHistory.org, courtesy Western Neighborhoods Project.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/ssf1918WW1B" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Newsreel footage of Armistice Day celebration in San Francisco, with thousands of parade-goers clad in influenza masks during the 1918 pandemic that swept the world.

Video: courtesy Prelinger Archives

As we deal with the effects of the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic, let’s look back at a similar global issue 100 years ago, the Spanish Flu pandemic that started in 1918. The Spanish Flu name may have been a misnomer. It acquired that name because Spain reported a bigger spread and more deaths from the epidemic than other countries. At the time, however, Spain was sitting out World War I and was not censoring wartime stories like countries involved in the Great War were doing.

Military doctors in France began reporting a new disease with a high mortality rate late in 1917. Several factors contributed to the spread of what became known as the Spanish Flu. Those factors included the close troop quarters and troop movements of World War I, soldier malnutrition that may have compromised immune systems, and better and faster modes of transportation that allowed infected people to travel further and faster than before. The first reported case in the United States was in Kansas in January 1918. Two months later, a company cook at Fort Riley in Kansas came down with it. Soon over 500 men at Fort Riley reported being sick. Cases were reported in New York in March 2018 as well.

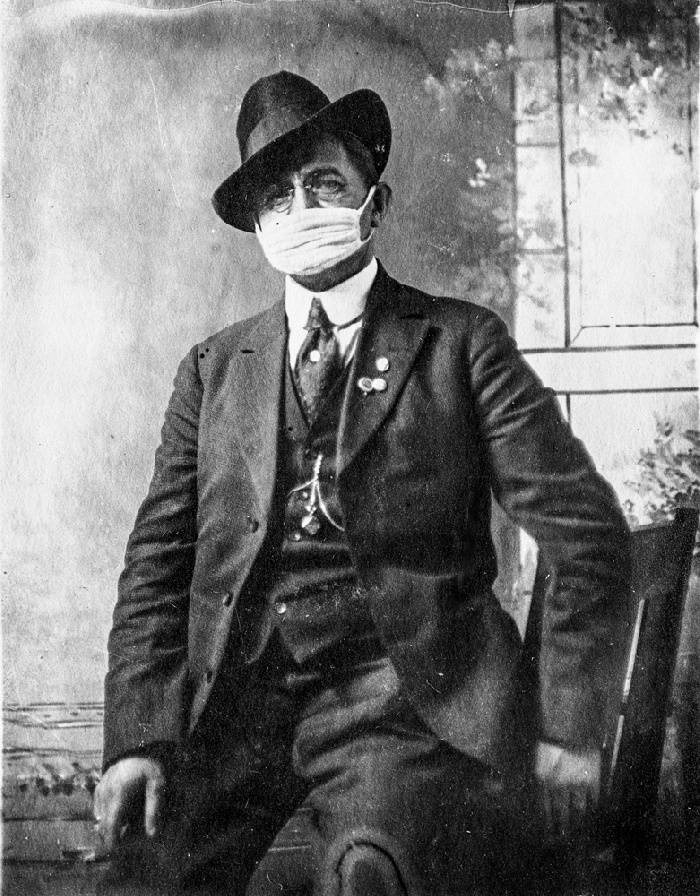

Man wearing influenza mask, 1918.

Photo: courtesy OpenSFHistory.org wnp26.1205; Norma Ball Norwood Collection / Courtesy of a Private Collector

In 1918 in Oakland, warnings to wear a mask.

Photo: public domain

On September 23, 1918, the first Spanish Flu case in San Francisco was diagnosed. Dr. William C. Hassler of the City Health Office, who oversaw San Francisco’s efforts to battle the deadly outbreak, determined that Edward Wagner had the deadly influenza and sent him to the hospital.(1) Wagner’s home on Eddy Street was placed on quarantine. Wagner had recently been in Chicago where doctors believed he had been infected. By the end of September, the State Board of Health had ordered that all cases of the Spanish Flu be reported to them and to isolate all patients with the virus.

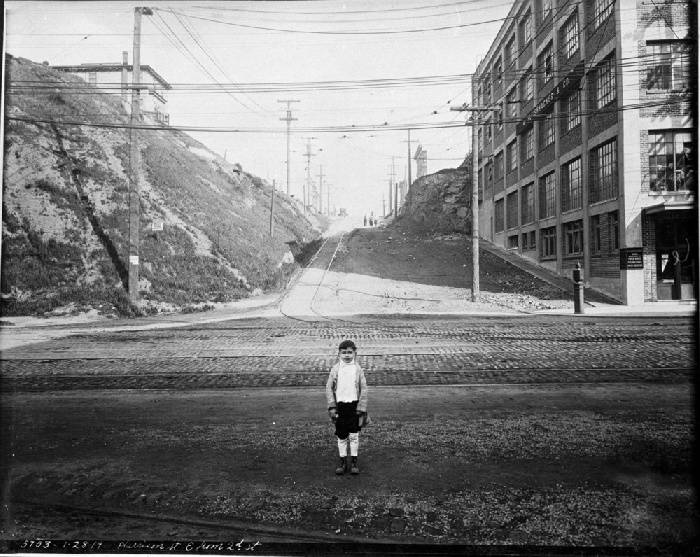

Boy with influenza mask pulled down at intersection of Harrison and 2nd Street, January 28, 1919.

Photo: courtesy OpenSFHistory.org wnp36.01997; DPW Horace Chaffee – SF Department of Public Works / Courtesy of a Private Collector

By the end of October 1918, San Francisco had over 18,700 influenza cases reported with a little over 900 deaths, although new case reports were starting to decrease.(2) Most of the deaths resulted from pneumonia that developed after the flu had ravaged immune systems. San Francisco hospitals were filled, so a new administration building for the Red Cross at Fulton and Hyde in the Civic Center area was quickly converted for use as a convalescent hospital. It began housing influenza patients at the beginning of November 1918.

Flag ceremony at Red Cross Building at Fulton and Hyde, November 1918.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp36.01945; DPW Horace Chaffee – SF Department of Public Works / Courtesy of a Private Collector

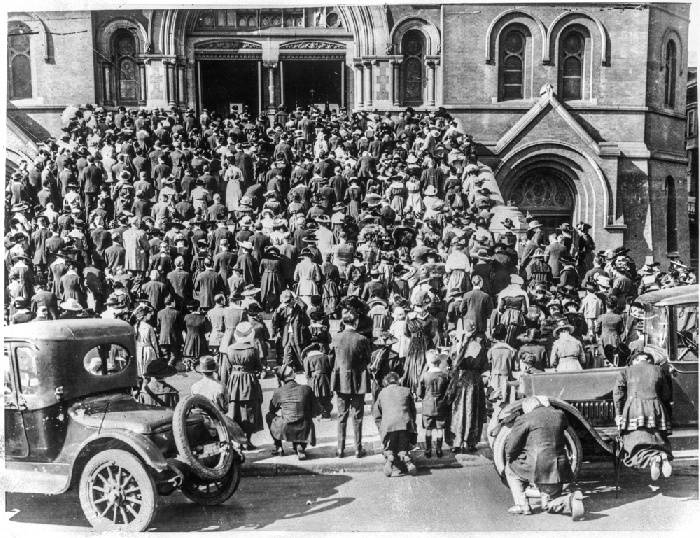

With the sharp increase in the spread of the Spanish Flu, San Francisco took a number of preventative measures. This included ordering people serving the public to wear masks and urging the public to wear masks while out in the streets,(3) and then later ordering people to wear masks while out in the public.(4) San Francisco also increased street cleaning efforts and ordered churches, schools, playhouses, dance halls, lodges, and all places of public amusement to shut down. Movie theaters showed instructions for prevention and treatment of the flu on screens before screenings. Residents were advised to avoid peak hours for streetcars, to take better care of the personal hygiene, and avoid crowds. The Presidio was closed to visitors by the middle of October.(5)

Outdoor Church Services St. Mary’s Cathedral Van Ness & O’Farrell, some wearing influenza masks, 1918.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp27.2985; Courtesy of a Private Collector

By the end of October 1918, a vaccine had been developed and distributed and inoculations in San Francisco began. Later studies showed that the vaccine was not effective against the influenza as medical professionals had not yet learned that it was caused by a virus. However, it may have helped lessen the fatality rate from the pneumonia that developed afterwards. The Spanish Flu pandemic began to decline by the end of 1918, but San Francisco experienced a flare-up in early 1919 that was attributed to the decreasing use of masks. The Board of Health therefore refused to remove mask requirements at that time,(6) but within a few days it was determined that the epidemic was over, so the mask requirement was ended.(7) While the Spanish Flu ravaged the world for the better part of 1918, San Francisco suffered from its effects for a period of a little over four months. Almost 45,000 cases of the influenza occurred in the City and over 3000 residents died. It was one of the cities hit the hardest by the Spanish Flu. Hopefully, the COVID-19 pandemic won’t last as long nor be as deadly.

Welcome Home Parade, April 22, 1919.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp30.0284

Notes:

1. “First Influenza Case Is Discovered in S.F.” San Francisco Chronicle, September 24, 1918, p. 8.

2. “Abatement of Contagion Shown Here” San Francisco Chronicle, October 31, 1918, p. 9.

3. “All Persons Serving Public To Wear Masks” San Francisco Chronicle, October 20, 1918, p. 42.

4. “The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919: San Francisco, California”.

5. “Presidio Closed Against Visitors” San Francisco Chronicle, October 15, 1918, p. 8.

6. “Board Refuses To Ask Repeal Of Mask Edict” San Francisco Chronicle, January 31, 1919, p. 1.

7. “Mask-Wearing Order Goes As Epidemic Dies” San Francisco Chronicle, February 2, 1919, p. 25.