Dow Wilson's Assassination: The Fight for Democracy in the Painters' Union

Historical Essay

by Herman Benson, from Rebels, Reformers, and Racketeers: how insurgents transformed the labor movement

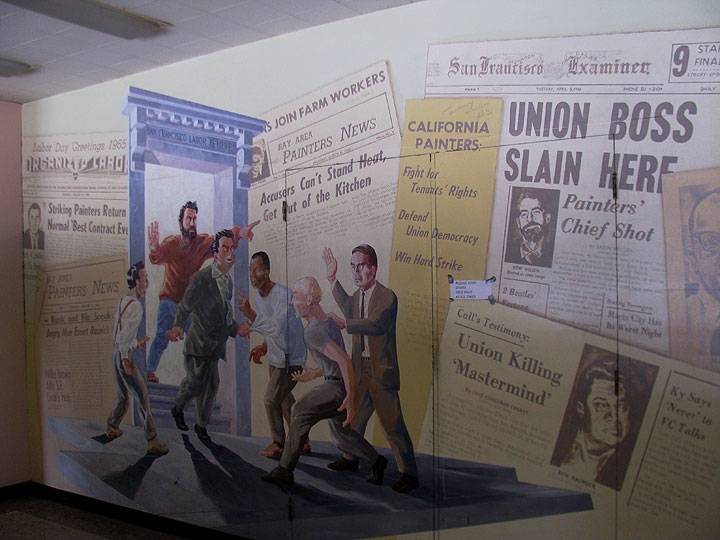

Aaron Noble’s piece illustrates two important moments in the City’s labor history—when the corrupt union official Ben Rasnick was thrown out of the Red Stone Building by Dow Wilson (depicted here); and, later, when Wilson was murdered by shotgun fire on April 5, 1966.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

One day in 1963, seated at his desk in the office of Painters Local 4, Secretary Dow Wilson, its leading officer, happened to glance into the wastebasket where the office clerk normally deposited the day's collection of junk mail. His eye caught the headline in an obscure little newsletter: "Our Day in Court." Curious, he picked it out and discovered issue No. 9 of Union Democracy in Action with the full text of Salzhandler v. Caputo, the New York painters' case in which the Court of Appeals, establishing a firm basis in federal law for civil liberties in unions, had voided internal union charges of slander against critics. Facing precisely such charges in his San Francisco District Council 8, he realized how important the decision could be for him. His local reprinted the UDA issue and distributed it to union activists all over the West Coast. He decided to link up with the reformers in New York.

That's how he got to know me and Frank Schonfeld. Within a few months he provided us with a bulging sheaf of documents, and for the next three years kept us informed. Early in 1966 UDA got a $1,500 grant from the Prynce Hopkins Fund which enabled me to write, print, and distribute the story of the California Painters in UDA No.18: "California Painters: Fight for tenants' rights; defend union democracy; win hard strike." When Wilson saw the advance text, he ordered several thousand copies for circulation in California. We did print the issue, but he never got the copies, because while we were awaiting delivery from the printer, his enemies in California were preparing to kill him. On April 5, 1966, he was shotgunned to death. Later, Union Democracy in Action told his story:

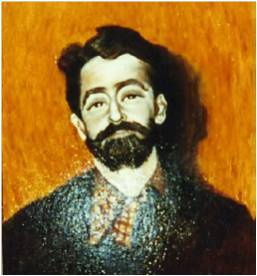

In 1963, Wilson, then 37, was known only to a small circle of admiring associates and a much smaller circle of bitter enemies; but his leadership qualities were exceptional. He could easily rally a hundred supporters to picket and protest. Flamboyant like John L. Lewis, he spiked his speeches with colorful phrases and literary quotations. No conformist, no suits, no white shirts, no ties. At a time when it was unfashionable, he sported a beard, black and visible, a blazing hunter's jacket and cap. He was murdered just as he was about to break out of obscurity into prominence as a national union leader.

Wilson was born in Washington DC in 1926, dropped out of high school to become a seaman. He married Barbara in 1946, became a housepainter, settled in San Francisco where they raised three children. In 1958 he was elected business agent of Painters Local 19, merged it with another to form Local 4 which, with its 2,500 members, became the largest single unit in the international brotherhood. As the local's recording secretary, he became its de facto leader, turning it into a powerful force in the painting industry and a respected factor in community affairs.

In New York City while the Painters' union under Rarback was running a criminal bid-rigging conspiracy in city housing painting, in San Francisco Wilson's local was exposing the cheating of the city, of tenants, and of the federal government in the painting of public housing. Ominously, he was denounced at the union's district council for upsetting "fine relations" between the union and the city's Housing Authority. He silenced his critics by assembling delegations of rank-and-file members to attend council meetings. Each Bay Area Painter local was assigned to one of three district councils. Some locals were authentic housepainter locals, but others were so-called autonomous locals on the periphery of the trade. Traditionally, the three district councils negotiated jointly with the employers' association.

Representation in District Council 8, which included Wilson's local, was gerrymandered by a lopsided system of representation which gave inordinate power to the autonomous locals and reduced the influence of the housepainters. Wilson's Local 4 with its 2,500 members was awarded five delegates to the council; one autonomous local with only 13 members got the same five. Wilson's supporters initiated a campaign for a new council structure based upon a democratic one-man, one-vote system. They successfully pressured the council to submit the plan to a membership referendum where it passed by a big majority: 1,277 to 379. But in October 1965, just as it later ruled against a New York DC 9 similar proposal, the international vetoed the change. Those who wanted the democratic reforms would not supinely submit. In November 1965, they published the first issue of their own tabloid, the Bay Area Painters News, to campaign for democratization of the council. The publication became the rallying force for reform forces in the Bay Area. Its first issue declared, "Power doesn't scare us. We want our rights. What country do they think we are living in? ... Now or never will we ever permit the G.E.B. [General Executive Board] to have that power of crass dictatorship."

The festering situation had come to a head earlier that year during a Bay Area five-week housepainters' strike, July 1 - August 6. Painters walked out when their union contract expired in June 1965. The three district councils had agreed, as usual, that none of their locals would settle without provisions for a uniform Bay Area contract. Wilson was elected to the bargaining committee; and, from that position, he became the effective leader of the strike. Then, without warning, while the strike was still on, District 33 unilaterally signed a separate contract with employers and ordered its locals back to work, undercutting those locals still on strike. One local in Wilson's District 8 and another in District 16 followed suit in abandoning the strike.

Wilson fought back. He mobilized mass picket lines; he brought mass delegations of strikers to meetings of locals in District 16, whose secretary treasurer, Ben Rasnick, was Wilson's bitter enemy. Despite DC 33's attempted defection, the strike lines held, and the stoppage remained solid. Three weeks later, after Wilson had led a two-front battle against the employers and against the sabotaging union officials, the strike was won. The victorious strike leaders boasted that 7,000 painters had achieved one of the finest contracts in the union's history. Later Wilson announced that he would be a candidate for vice president of the international and initiated a national campaign to round up support.

Convinced that high-ranking union officials had been paid off to try to break the strike, Wilson publicly denounced local officials who had led the back to work movement as "finks and strikebreakers." He reserved choice words of opprobrium for Ben Rasnick, whom he excoriated as a "scabherder."

Wilson had defeated the employers; he had fought off the sabotaging area union officials. Now, he faced an attack from the union's international officialdom. When Wilson's enemies charged him with slander, the international office, bypassing the locals, took over the trial proceedings and dispatched two international representatives to investigate Wilson. As the trial opened in November 1965, a delegation of 300 painters protested; the American Civil Liberties Union asked for the right to monitor the proceedings, and Congressman Phil Burton protested.

The trial soon had to be abandoned; because the central charge against Wilson ---"slander"--- clearly violated the federal court decision in Salzhandler.

The union's general counsel, Herbert S.Thatcher, had represented it in an unsuccessful appeal to the U.S.Supreme Court against Salzhandler, the very decision which made the slander charge against Wilson illegal. When Thatcher was rebuffed by the Court, he knew that the charge against Wilson could not stand up.

After three days of testimony, the trial committee suspended the effort to suppress Wilson, but only for the time being. Under federal law, it could not validly find him guilty; but it would not declare him innocent. Leaving an overhanging threat, an ambiguous verdict sounded this ominous warning: "...the present charges against Brother Wilson should be dismissed without prejudice to the renewal of such charges or similar charges should it become necessary to do so and if a repetition of the conduct alleged in the charges should thereafter take place...."

"I firmly believe," wrote Wilson in the Bay Area Painters News on December 20, 1965, "that further attempts will be made to nail my hide." Tragically, his prediction proved accurate. Success in beating off the illegal prosecution actually led to a verdict of death for Wilson. He had become a dangerous threat to a corrupt conspiracy. Only his death could remove that threat.

Dow Wilson.

Image: courtesy San Francisco City Workers United

By early 1966 Wilson's reputation in the union had extended nationally, as a militant unionist, a stand-up guy who could fend off employers and arrogant union officials; other locals looked to him for leadership. Sacramento Local 487, impressed by his achievements, asked him to represent it in negotiations. At this point he became suspicious of the management of the local's Health and Welfare Fund. Working closely with Wilson was Lloyd Green, secretary of Local 1178 in Hayward; Green was a leader in opposition to Ben Rasnick, secretary treasurer of District Council 16, the "scabherder" target of Wilson's barbs.

As April 1966 drew near, copy had been completed for UDA No. 18 with its background story of Wilson's battle; but it had not yet come back from the printer. "The strike is won," it reported, "the trial is over. The campaign for internal democracy in the Brotherhood of Painters continues. A notable success has been recorded in California."

It was late afternoon, New York time on April 5, 1966, that I got the horrible news. Morris Evenson, Wilson's second in command, phoned from San Francisco to say that Wilson had been murdered late that night by three shotgun blasts to the head. So far, by parties unknown. He was so terribly upset that he could say no more. I felt a heavy responsibility to do something, something. If we hadn't saved Wilson in his internal union trial, he might still be alive. I knew it was a crazy thought, but I couldn't repress it. But what to do? What do you do when someone you've been working with is murdered? Isolated and without resources in my little Manhattan apartment, what could I possibly do? I owned no copying machine. No computers, no faxes, no internet in those days. How to let the world know?

The full battery of modern technology at my disposal was a 20-year old manual Royal typewriter with a faded ribbon, a telephone, a stack of ultra-thin (now obsolete) onion skin sheets, and fine carbon paper. Total staff: me and my wife, Revella Benson. We phoned all New York dailies, called major local radio and TV stations. No one interested. Luckily, we had accumulated one bit of capital: Union Democracy in Action No. 18. The issue had just arrived from the printer, only a 4-page newsletter; but it reported the first full account of Wilson's battle in California.

Press releases! With that old typewriter and onion skin, six near- legible copies could be tediously tapped out at a time if you hit the keys hard enough. But it didn't have to be long: "Dow Wilson murdered in San Francisco. For background and significance, see enclosed issue of Union Democracy in Action. Call for more information." We mailed the crude release, along with UDA No 18, to the dozen leading national dailies whose addresses were readily available. All ignored us, except one. But that was a big one.

Somehow, the amateurish product reached the city editor at the Washington Post, who passed it on. "Frank, this may interest you," he said to Frank Porter, the paper's labor editor. (Later, Porter told me and Schonfeld that he had been a seaman in his youth and could understand the battles of unionists for justice.) Porter phoned the Post's office in San Francisco, verified the accuracy of the murder report, and flew to New York City to meet with me and Frank Schonfeld. Three weeks later, he broke the story in a long four-part major series, April 24-27, beginning on the first page of the Post's Sunday edition. The story of Dow Wilson, Frank Schonfeld, and the painters' battle for reform now was national news. And just in time.

A few days later, on May 8, Lloyd Green, leader of Painters Local 1178 in Hayward and Dow Wilson's close collaborator, was the next to die. As Green sat in his office, the killer fired through the window and blasted him to death with a shotgun. Again, it was horrifying and frightening. Again--- What to do? What to do? What to do? The murderers were still unknown and at large.

There was Norman Thomas, still with us. He agreed to sponsor a "Citizens Committee for an Investigation of the Wilson-Green Murders and of Racketeering in the Painting Industry." In 1959 for the two expelled machinists, we had managed to enroll a tiny support committee of three. By this time, however, Union Democracy in Action had been at work for more than six years and now had a following, small but respected. With the help of Rochelle Flanders, a close friend, not working, we enrolled more than 20 co-sponsors in addition to Thomas, including Algernon Black, Irving Howe, Mike Harrington, Msgr Charles Owen Rice, Father Philip Carey, Meyer Shapiro. The committee called for an investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice. Gordon Haskell, then ACLU development director, and I became committee co-coordinators. (Soon thereafter, Flanders was hired by the United Federation of Teachers to help edit its newspaper.)

Late in May 1966 the case cracked open when Norman Call and Max Ward, two employer insurance fund trustees, were indicted in state court for the murders, along with three fund administrative employees, revealing a conspiracy to defraud the funds of hundreds of thousands of dollars. Two days later Sture Youngren, the fund administrator, committed suicide after confessing to stealing $60,000. In September Ward and Call were convicted of murder; the charge against the other three was reduced to embezzlement.

In the San Francisco Bay Area local unions mourned the deaths and marched in protest. But, despite the mounting pressure of publicity, not the AFL-CIO under George Meany, nor the Painters international, nor any AFL-CIO affiliate bothered to note these events or to express horror at the assassination of two labor leaders. When pressed, Frank Raftery, Painters' international president, shrugged it off. "Those who live by the sword," he told one reporter, "die by the sword," an enigmatic remark —really stupid— because it was Rasnick who lived by that sword!

The AFL-CIO national Building Trades Department commented, but only to clear its skirts. It affirmed vehemently that no one in "labor" was responsible, that "labor" was clean. But its public relations reassurance and self-consoling stance was brutally upset when Norman Call, convicted of murder, came up for sentencing in September. Anxious to avoid the death penalty, he confessed that after Wilson had beaten off the slander charges at the union trial, Rasnick had ordered the murder. He revealed that after the internal union charges against Wilson had bombed, Rasnick directed the two "to go ahead and make plans for him to be killed." And there was more. Ward's wife had been sleeping with Rasnick. She testified that, in a moment of unguarded intimate indiscretion, Rasnick had admitted ordering the killings. He was convicted and sentenced to life.

The story was now wide open. On July 6, 1967, the Wall Street Journal ran one of its major investigative pieces on the Painters union, reporting on reform movements and corruption scandals not only in New York and California, but Buffalo, Minneapolis, and Washington, DC. Business Week and Time published stories. Even the New York Times broke down and ran a small notice.

In Washington DC Painter reformers exposed widespread cheating in the painting of government buildings. The Washington Post reported, "One coat instead of two was used on a repainting job last year at C.I.A.'s headquarters in Langley. That job was done at night under such secrecy that union stewards were not allowed to make sure that the painters' contract was not violated." A fine example of C.I.A. vigilance!

Meanwhile, back in New York City events were coming to a head. Martin Rarback, secretary treasurer of District Council 9 in New York had been indicted for bid-rigging. The international imposed its mock trusteeship over the council which left the corrupt status quo unmoved.

With Ben Rasnick indicted for murder, the pretense that the killing was unrelated to the battle for union reform could no longer hold water. An AFL-CIO executive council meeting was scheduled for February in Florida. In preparation for the sessions, reformers in New York and in California drafted an appeal to the AFL-CIO Ethical Practices Committee, outlining the long history of corruption, blacklisting of critics, stolen elections, beatings and murder of dissidents, sweetheart deals with employers. They asked the AFL-CIO to remove the top officers of the Painters union and restore democratic rights in the union. Evenson and Schonfeld flew down to Florida to deliver their message. But their appeal never reached the EPC; by that time the committee was defunct and the Ethical Practices Codes were a dead letter. But they did get national attention. The Miami Herald ran a front page, full-sized, photo of George Meany receiving the text of the appeal from the hand of Morris Evenson.

Meany, now under mounting public relations pressure to do something, appointed a committee. It performed its expected servile service. After a cooling off cycle, and without bothering to interview even a single complainant, it advised Meany that there was nothing to do, which he did.

Postscript: In California the battle culminated in an uneasy stalemate. With Wilson gone, his friends held on in District Council 8, but only as an island, as a redoubt of independence from a suspect international office. Without his driving force, his talent for mobilizing support in the union and in the community, they lacked the ability and the fervor to use their local strength as the springboard for a national reform movement. With the murder of Wilson and Green, the reform lost its vital spark and the impetus for a national reform movement was dissipated. However, that ten-year reform record in New York, California, and elsewhere remains as evidence of the potential for democracy and reform in the labor movement.

And in this case, it had a more immediate and more lasting effect. The painter's battle shaped union democracy law through the decision in Salzhandler and established a firm statutory base for civil liberties in unions. And their ordeal prompted the formation of the Association for Union Democracy. Many of those who had joined the Citizens Committee for Wilson and Green as an ad hoc formation in 1966 agreed to sponsor AUD as a continuing organization in 1969.

From the website of the Association for Union Democracy. www.uniondemocracy.org. Email: [email protected]. 104 Montgomery Street, Brooklyn, New York, 11225; USA; 718-564-1114