New Year's Eve Jan. 1 1965: A Night for Gay Rights

Historical Essay

by Amanda Harbrecht

| San Francisco is known as an important center for LGBTQ rights. A significant but often overlooked event in the history of this movement is the 1965 New Year’s Ball and subsequent police raid. This event brought attention to the police discrimination against homosexuals, it challenged the imagined and experienced landscape of homosexuals at the time, and it represented the beginning of new political influence exercised by homosexuals. |

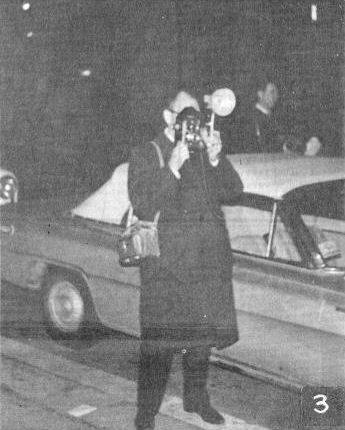

Photo by San Francisco Examiner photographer Ray “Scotty” Morris, January 1, 1965.

Photo: GLBT Historical Society of Northern California

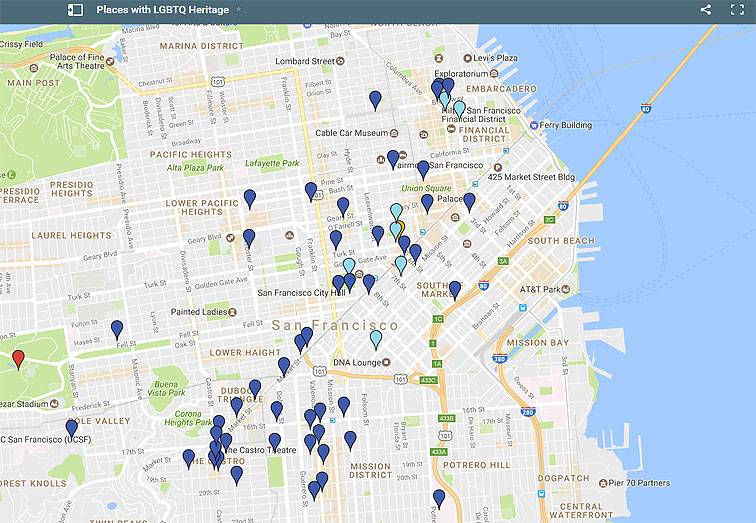

The mid-to-late-1900s represented an important time for the LGBTQ community. As part of an effort to identify and recognize historically important sites for the LGBT movement, the National Park Service compiled an interactive map of sites that may qualify for national landmark status.

Historic sites associated with LGBTQ life in San Francisco.

Red tags indicate sites that are already on the National Register of Historic Places, which primarily includes locations of LGBTQ associations. Blue tags represent sites that either are not listed, or are listed but not in relation to their LGBT significance. As seen by this map, San Francisco represents a main hub for this cultural revolution in the U.S. Within San Francisco, neighborhoods including The Castro, the Mission District, and South of Market, are especially populated with tags. Amongst these markers is one located at California Hall between Turk and Polk Street.

California Hall on Polk Street at Turk. This is the site where police raided a New Year’s Eve Ball in 1964. This New Year’s Ball was important for three reasons: it brought attention to the police discrimination against homosexuals, it challenged the imagined and experienced landscape of homosexuals at the time, and it represented the beginning of new political influence exercised by homosexuals.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The Council on Religion and the Homosexual, or the CRH sponsored the New Year’s Eve Ball. This group was formed in order to increase discussion between clergy and homosexuals. The organization’s goal was to promote homosexuals as belonging and being a part of mainstream society (Sides, 2009). Despite the CRH having filed the proper permits and even meeting with the sex crime department of the SFPD, problems with the police arose that night. Over 20 officers showed up blocking the intersection, photographing event attendees, and harassing them.

Police photographer outside hall. Movie cameraman in background. The photo above features one such photographer for the police, not inconspicuously photographing the event attendees. In the background someone filming the event can also be seen. This type of invasion of privacy for the event and its guests showed a clear disregard by law enforcement for this community and their rights as citizens. There were even a few arrests made (Sides, 2009). CRH leader Chuck Lewis can be heard describing the event and the arrests. In the clip Lewis explains that there were two still photographers taking pictures of everyone who came and left, as well as a movie camera filming the night. He also explains that police squads repeatedly entered the private event for “fire inspections” (The Council of Religious and the Homosexual).

Photo: courtesy LGBT Religious Archives Network

While certainly unfair and unprovoked, this police raid was far from an anomaly. Police raids of gay bars and clubs were frequent occurrences. The New Years Eve 1965 raid actually served the homosexual community due to the unprecedented media coverage that followed. For years the abuse and discrimination of homosexuals by the police had been off the radar, but this event had been intended as an opportunity for homosexuals and heterosexuals. Amongst the lesbians, gays, and drag queens, the event was also attended by clergymen, their wives, their friends, and even their lawyers (Sides 2009). The publicity that followed was unprecedented and served to bring the struggles of the homosexual community to the attention of mainstream America. Press conferences and newspaper articles alike raised awareness of this event and sympathy for the LGBTQ community. This negative press was so powerful that it represented a decrease in police power. No longer were police free to harass the homosexual community; hence forward, “the SFPD stopped arresting gay men for doing ‘what was wrong’ and only arrested them for a ‘violation of the law’” (Sides, 2009).

The police raid of the 1965 New Year’s Ball also challenged the imagined and experienced landscapes. Both the way public spaces were perceived, as well as how people interacted in public was changed. Public spaces had never been safe, much less welcoming for the LGBTQ community. The LGBTQ community imagined San Francisco as a safe place for them to be themselves, yet many conservatives saw San Francisco as having no place for those groups. As Sides notes, “Because many San Franciscans believed that public spaces could only serve mutually exclusive social purposes, the gay revolution provoked heated, even violent, exchanges over the destiny of urban space” (Sides, 2009). Even in spaces that were supposed to be designated for the gay population, there could be repercussions. Police raids of gay bars and clubs were frequent, as well as officials shutting down establishments for the gay community. It wasn’t until a Supreme Court ruling in 1951 that overtly gay bars were protected from being shut down because of their clientele. The bar behind this case was the Black Cat Café on Montgomery Street. The Black Cat Café was an important location for the gay rights movement for other reasons as well, including its role in developing a sense of fun and humor for the gay community.

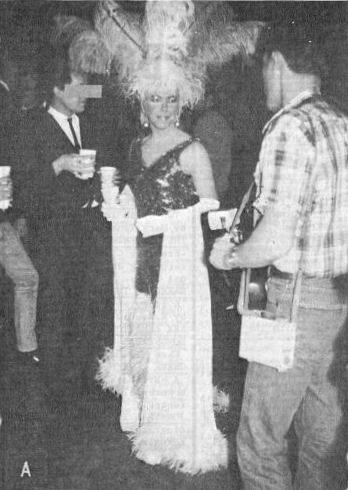

From the New Year's Day Ball at California Hall, published in Citizens' News

Photo: courtesy LGBT Religious Archives Network

Even once these bars had achieved a certain level of legitimacy, they were still far from free spaces. Most bars did not allow touching or dancing. This was one reason private dances were so important to the LGBTQ community (Sides, 2009). They allowed a greater freedom for those individuals where the experienced landscape could be one where they were able to be themselves. This can even be seen in the events leading up to the 1965 New Year’s Eve raid. When CRH members had met with officials originally, the police argued that no one at the event could be dressed in drag to which the CRH members pointed out that it would be a private event and hence the police could not dictate dress (The Council of Religion and the Homosexual). Again, this is another example of the conflicts between private and public spaces and the disagreements that existed regarding those spaces.

It was the first gay rights case the ACLU got involved with (The Council of Religion and the Homosexual). After the ACLU won the case, the police department actually appointed a liaison to the LGBTQ community (Yogi, 2007). Thanks to the publicity generated by the CRH, the event was brought to the attention of San Francisco Mayor John Shelley. He held Police Chief Thomas Cahill responsible, and inquired into a full account of what had transpired (Yogi, 2007). The event also created greater awareness around the CRH, which increased their power and influence. The group’s next initiative was to organize San Francisco’s first candidates’ forum for gay and lesbian voters. As Yogi writes, “Within just over a decade, these nascent efforts built to a point that Harvey Milk became one of the first openly gay elected officials in the country when he won a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors” (Yogi, 2007). These are all examples of the changed political climate that was a direct result of the New Year’s Eve raid.

Bibliography:

Sides, Josh. Erotic City: Sexual Revolutions and the Making of Modern San Francisco. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

The Council of Religion and the Homosexual. The LGBT Religious Archives Network. Online Exhibit. Accessed November 12, 2016.

Yogi, Stan. “The Night San Francisco’s Sense of Gay Pride Stood up to Be Counted.” SF Gate. June 24, 2007. Accessed November 12, 2016.