People's Wall: "Our History is No Mystery" mural

Historical Essay

by Alan U. Barnett

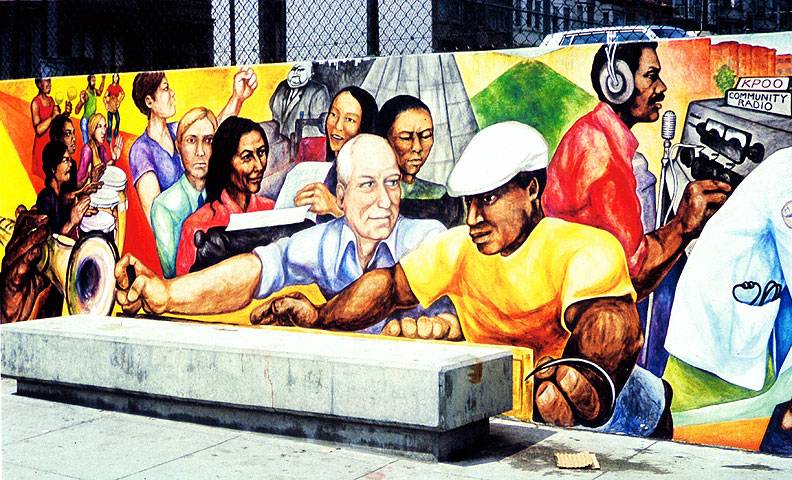

Detail from "Our History is No Mystery" at Hayes and Masonic.

Photo: courtesy Jane Norling

Our History is No Mystery, 1976, Masonic at Hayes, by Haight Ashbury Muralists.

Photo: Tim Drescher

Besides the work that the Haight-Ashbury Muralists had done for the Modern Art Museum exhibition, they painted another and much larger working people's version of American history that year in an effort to correct official Bicentennial sagas. Two of the painters, Miranda Bergman and Jane Norling, had recently been in Mexico and were impressed by Rivera's historical panoramas.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/PeoplesWall" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Video: courtesy Mark Freeman Films

"Peoples Wall" is a 22-minute documentary about the mural "Our History is No Mystery," which was created in 1976. It was on the wall of John Adams Community College at Masonic and Hayes in San Francisco, CA. After continuing defacement--some of which was documented in the film--the mural was redesigned and repainted. Haight Ashbury Muralists: Jane Norling, Vicky Hamilin, Thomas Kunz, Miranda Bergman, Arch Williams, Peggy Tucker. The film was made by the Haight Ashbury Film Collective, which included Mark Freeman, Claire Schoen, Jack Wilson and MJ White.

Jane Norling painting "Our History is No Mystery", c. 1976.

Together with Arch Williams, Vicky Hamlin, Peggy Tucker, and Thomas Kunz, they created an eight-foot-high, three-hundred-foot long mural on a retaining wall around the yard and parking lot of the John Adams Community College. Starting in the summer of 1975, they finished only the following May. They called it Our History Is No Mystery and said in the handbill that they distributed to passersby that the mural was "about the real makers of history." They continued:

Working people have created everything. History is not just the story of rich men, presidents and kings — it is the story of the building of societies by the creative energy of human hands, by the sweat and blood of the working people, by the joy and power of people's cultures, and by the struggles against oppression. The mural consists of a series of scenes of San Francisco history beginning with the Indians and moving forward through the frontier, the Chinese working the mines and railroads, the Longshoremen and General Strike of 1934, war work in the shipyards in the forties that brought many Black people to the city, the interning of Japanese-Americans in concentration camps, and the demonstrations of the sixties and seventies with portraits of Malcolm X and George Jackson. These history panels merge into scenes of present-day workers: a woman is shown high in the air repairing a telephone line as another happily fries an egg while holding her infant, implying the need for women to have a choice. Farm workers are harvesting cabbages, and free food is distributed to the poor; a Black woman doctor cares for a patient, while a Black male station engineer operates community radio equipment; and technicians of different races and sexes are shown working together. The artists also brought to the attention of passersby the ongoing struggle of the International Hotel by quoting from its mural. They took a few imaginative liberties by including Paul Robeson, Siqueiros, and Rivera and his painter wife, Frida Kahlo, in the procession of picketers during the 1934 General Strike to suggest their sympathy with it, though not their presence. The young muralists seem also to refer to their own effort to learn from these earlier "cultural workers." In order to strengthen the sense of reality, Jane Norling, one of the painters, says they did "invented portraits," giving a number of faces the idiosyncrasies of actual persons by synthesizing details from photographs. The total result is a monumental but also a vernacular reinterpretation of American history. It is an eye-level chronicle painted by the trained and untrained without the magniloquence of official memorials. It clearly meant something to its residential neighborhood, for when it was vandalized more than thirty people came out to restore it.