Eastern SOMA Early 20th Century

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

200 block of Beale Street in approximately 1890, looking east from Minna Street.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp15.015

In 1900, nearly one San Franciscan in five lived South of Market, in the area between Market and Townsend, from the waterfront to Eleventh Street, the most densely populated part of the city except for Chinatown. Warehouses stood near the piers and along Townsend Street, interspersed with considerable manufacturing. Howard Street between Main and First was the center of a number of foundries and machine shops. Breweries, boot and shoe factories, furniture factories, paint and varnish plants, packing box makers, and the like lined the streets south of Market. The area closest to the waterfront contained the homes of many sailors and waterfront workers, as well as some workers in the factories and plants of the area. Along the waterfront, males made up almost 70 percent of the residents in 1900, and nearly 90 percent in 1910. Somewhat to the west were more women and families proportionately, but less so in 1910 than in 1900. Half the population was foreign-born with Irish, Scandinavians, and Germans most prominent. Citywide, the average dwelling held 6.4 people, but here the average stood at ten in 1900 and nineteen in 1910.(6)

San Francisco at the turn of the century had more boatmen and sailors than any other American city, more even than New York. In 1890, one working male in forty found employment as a seafarer, and by 1910 the proportion of sailors and deckhands among working males had increased to one in thirty-two. When other waterfront workers—longshoremen, warehousemen, and so forth—are added to the seafarers, the waterfront provided employment to one of every twenty employed males in 1910. This proportion had not changed as late as 1930.(7) Along the streets near the waterfront stood sailors' boardinghouses, saloons, restaurants, and places of amusement catering to young, single men.

Boardinghouses did more than just provide a place to sleep when in San Francisco. There sailors could buy provisions (often on credit), relax in the saloon, borrow money, and secure employment. Boardinghouse keepers served as middlemen between ships' captains and boarders; they were, in fact, virtually the only way to find a job on a ship. The Yakela family ran one such boardinghouse at 214 Steuart Street. John Yakela kept a saloon on the ground floor and lived in the building with his wife and three children. All but the youngest Yakela, twelve-year-old Edward, had been born in Finland. Seventy-three sailors made their home at 214 Steuart, although most of them, at any given time, were away from the city aboard ship. There were few “old salts” at Yakela’s—only two were over forty-five, and the oldest was fifty-two. Two were younger than twenty-three. Eighty percent were between the ages of twenty-three and forty. More than half the boarders were Scandinavians (twenty-nine) or Finns (eleven). The other thirty-three came from a dozen different ethnic backgrounds, with Germans most numerous (ten), followed by English (five). Only three had both parents born in the United States.(8)

The prominence of Scandinavians at Yakela’s boardinghouse is not surprising, for San Francisco’s Scandinavians were concentrated overwhelmingly in seafaring. Throughout the late nineteenth century, over a third of those from Sweden, Norway, and Denmark found employment as boatmen or sailors. In 1900, those of Scandinavian parentage made up 5 percent of the city's total work force but 38 percent of the sailors and boatmen. Finns were not listed in the census, but they were so prevalent in the coasting lumber trade that steam schooners carrying lumber were called “Russian-Finn men-of-war.” A survey by the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific at the turn of the century showed its members to be 40 percent Scandinavian, 11 percent Finnish, 10 percent German, and only 9 percent American-born.(9)

Sailors were not the only single males living in boardinghouses South of Market. Migratory casual workers—hoboes and tramps—came to San Francisco, especially during the winter months or during periods of economic depression. Miners who worked in the Sierra, sailors employed in fishing off Alaska, agricultural workers from the interior valleys, and lumbermen from along the coast would come to the city with a “stake” when winter weather prevented work. This pattern seems to have intensified during the early twentieth century. The rebuilding after the destruction of 1906 included few of the houses and flats typical of streets like Natoma, Tehama, and Minna before 1906 and, instead, more institutions catering to single males. By 1910, the area was largely male, an area of cheap hotels and lodging houses, saloons, pawnshops, and missions. During December 1913, a survey was made of the “ten and fifteen cent lodging houses and the cheap hotels of the foreign quarter” (South of Market and parts of North Beach and Downtown). Forty thousand seasonal laborers were counted “lying up” in San Francisco, with a winter stake estimated to average thirty dollars. Within South of Market, seafarers and waterfront workers usually stayed east of Third Street, seasonal workers such as loggers and miners between Third and Sixth, and clerks and low-paid white-collar workers west of Sixth.(10)

Before 1906, however, many families lived South of Market. Then, much of South of Market consisted of two- or three-story wooden rowhouses packed so tightly that their backs almost seemed to meet as well as their sides. Larger masonry buildings stood along Mission and along some of the other major thoroughfares, but on the narrow, residential alleys that ran east and west, parallel to the major thoroughfares, wooden residential buildings were the rule. The description of South of Market provided by kindergarten director Kale Douglas Wiggin for 1878 needs little amendment for the period before 1906:

The scene is a long, busy street in San Francisco. Innumerable small shops lined it from north to south; horse[-drawn street] cars, always crowded with passengers, hurried to and fro; narrow streets intersected the broader one, these built up with small dwellings, most of them rather neglected by their owners. In the middle distance were other narrow streets and alleys where taller houses stood, and the windows, fire-escapes, and balconies of these added great variety to the landscape, as the families housed there kept most of their effects on the outside during the long dry season.

Still farther away were the roofs, chimneys, and smokestacks of mammoth buildings—railway sheds, freight depots, powerhouses, and the like—with finally a glimpse of the docks and wharves and shipping.(11)

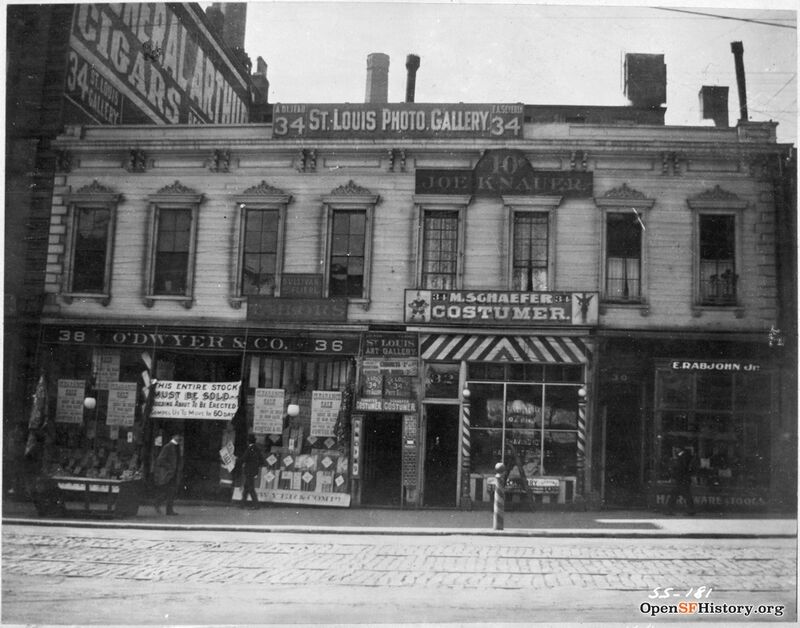

West side of Third Street between Mission and Stevenson, c. 1890.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp71.2005

Tehama Street, thirty-five feet wide, running parallel to and between Howard and Folsom streets, is one of these narrow residential streets. In 1900, 120 people lived on the south side of Tehama between Second and Third streets. Thirteen houses contained twenty-four households, twenty-two of them based on kinship. Forty-nine of the street’s seventy adults lived with a relative. Seven families had a boarder not related by kinship or marriage, three families had two boarders, and one had six. Although not related by kinship, boarders typically came from the same ethnic group as the family with whom they lived. Only two households, of two people each, consisted of people not related by either kinship or marriage. Six families included only two or three members, seven had four, nine had five or more. Eighteen of the twenty-two families had both husband and wife present. Of the seventy adults, thirty-three had two Irish parents and another four had one Irish parent. Seven had German parents, five were Scandinavian, and the rest came from a dozen different ethnic backgrounds. Only one had both parents born in the United States.(12)

Thirty-eight of the forty-one adult males on Tehama Street had identifiable occupations, as did nine of the twenty-nine adult women. Eighteen of the men’s occupations required little skill or training—day laborer, hod carrier, longshoreman, hackman, sailor, fisherman. Several were somewhat more skilled: a fire captain, sailmaker, plumber, tailor, iron moulder, stationary engineer, and boilermaker. Two were small businessmen—one a saloonkeeper and another a fruit peddler. The adult women included four who did laundry, two nurses, an actress, a house cleaner, and a landlady. Residence and kinship were often related to work. Timothy Gill and his wife Bridget had six boarders, one of whom tended bar in Gill’s saloon. Two of Gill’s other boarders were marine firemen. The Quinn brothers worked as warehousemen (one of them a foreman), perhaps at the same location. Three washerwomen lived in the same building. Clarence van Tassel lived with his brothers family, and both brothers worked in a factory making wooden boxes. Joseph Stromberg and John O'Hara, both teamsters, lived in adjoining buildings as did George Dreisbach and Samuel Levein, both tailors. Two nurses were mother and daughter.(13)

The area around the 100 block on Tehama was characteristic of South of Market more generally. At the end of the block, between Mission and Folsom on Third Street, stood seven restaurants, fourteen lodging houses, and thirty-two saloons. Kate Douglas Wiggin observed that “all the most desirable sites were occupied by saloons," and, she added, “it was practically impossible to quench the thirst of the neighborhood.” Up Third Street and around the corner on Mission loomed St. Patrick’s Church, largest parish west of the Mississippi. The Salvation Army had a spot on the same block, and Congregation Beth-Menahim Streisand was on the other side of Fourth Street, a bit south of Mission. Nearby blocks also included an Episcopal mission, a German Methodist church, a Methodist church, and a Presbyterian church. Other churches of major Protestant denominations and several other Jewish congregations were scattered through the South of Market region. Jefferson Primary School was down Tehama near First Street, St. Patrick’s school was almost the same distance in the opposite direction, and there was a Hebrew school maintained by the Jewish Educational Society. The Grand Opera House stood on Mission near Third Street, and the Young Men’s Institute, a Catholic organization, was on Fourth Street near Market. Irish-American Hall was down Howard, across Fourth Street. Federation Hall, across the street, was the meeting place for the Bakers’ Union, the Laborers’ and Hodcarriers’ Union, and the United Brotherhood of Labor. Several printing trades unions met up Third Street, near Market. Although the area showed a high concentration of restaurants (a third of all in the city) and lodging houses (half of all in the city) as early as 1880, the area continued to include many working-class families, at least until the 1906 earthquake and fire, and to include family institutions such as schools and churches, and a range of ethnic institutions as well.(14)

Despite the number of families (before 1906) and social institutions, a pattern of deprivation comes through even in the bare data collected by the census taker in 1900. Joseph Lesaudro, a day laborer, his wife Josephine, their four children, and Josephine’s sister and her husband were one of the five families living at 163 Tehama. The oldest Lesaudro girls, ages ten and twelve, were employed as hatmakers. A Polish widow and her three children rented the house next door; she worked as a housecleaner to keep her children in school and rented space to two lodgers, both also Polish, one of them a saloon cook and the other a baker’s helper. Michael Ryan, a day laborer, rented half of 155 Tehama. His two boys, ages fourteen and thirteen, both worked, and the family had a boarder. Charles Robert, a French-born dishwasher, rented 149 Tehama with his wife and four children. The two older children, ages thirteen and sixteen, were both employed. Denise Bailey, 153 Tehama, was the sole homeowner on the block. She rented rooms to five families in addition to her own, took in two boarders with her own family, and her two oldest daughters, ages fifteen and eighteen, worked as cigarmakers. Two blocks north of the Lesaudros, Ryans, Roberts, and Baileys stood the Palace Hotel, the most luxurious hotel in the world at the time it opened, and across the street from it was another luxury hotel, the Grand. Only a few short blocks separated luxury and poverty, success and hardship. Guillermo Prieto, in 1877, was struck by the same contrast: “Behind the palaces run filthy alleys, or rather nasty dung heaps without sidewalks or illumination, whose loiterers smell of the gallows.”(15)

East on Townsend Street from 4th Street, August 1925.

Photo: Jesse Brown Cook collection, online archive of California I0050719A

Folsom Street east from 3rd Street, May 26, 1937.

Photo: SFDPW, courtesy C.R. collection

Notes

6. Table 104, “Population, Dwellings, and Families, for Places Having 2,500 Inhabitants or More: 1900,” ibid., vol. 2, pt. 2, p. 640; Table 23, “Population by Sex, General Nativity, and Color, for Places Having 2,500 Inhabitants or More: 1900,” ibid., p. 610; Table 5, “Composition and Characteristics of the Population for Wards (or Assembly Districts) of Cities of 50,000 or More,” U.S. Bureau of the Census, Department of Commerce and Labor, Thirteenth Census of the United States: Abstract of the Census with Supplement for California (Washington, D.C., 1913), p. 616. The relevant assembly districts for the 1900 census are the 28th through the 31st; for 1910, the 28th through the 30th. For a good history of the region, see Alvin Averbach, “San Francisco’s South of Market District, 1850-1950: The Emergence of a Skid Row,” California Historical Quarterly 52 (Fall 1973): 197—223; Averbach cites numerous studies of various aspects of the area and the observations of various visitors.

7. Table 118, “Total Males and Females 10 Years of Age and over Engaged in Selected Occupations, Classified by General Nativity, Color, Age Periods, Conjugal Conditions, Illiteracy, Inability to Speak English, Months Unemployed, and Country of Birth, for Cities Having 50,000 Inhabitants or More: 1890,” Eleventh Census of the United Stales: 1890, vol. 1, pt. 2, pp. 636-639, 702-703, 704-705, 728-729; Table 3, “Total Persons 10 Years of Age and over Engaged in Each Specified Occupation, Classified by Sex, for Cities of 100,000 Inhabitants or More: 1910,” Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1910, 4: 200–201; Table 3, “Gainful Workers 10 Years Old and over, by General Divisions of Occupations,” Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930 4:173.

8. U.S. National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, 1900 Federal Population Census Schedules, microfilm, T623, roll 100 [hereafter cited as 1900 Census Schedules]. See also Jerry P. Schofer, Urban and Rural Finnish Communities in California: 1860—1960 (San Francisco, 1975), pp. 31–34; Hyman Weintraub, Andrew Furuseth: Emancipator of the Seamen (Berkeley. 1959), pp. 5, 6; James Fell, British Merchant Seamen in San Francisco, 1892–1898 (London, 1899); State of California, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Investigation into Condition of Men Working on the Waterfront and on Board Pacific Coast Vessels, San Francisco, June 29—July 10, 1887 (Sacramento, 1887); “Boarding Houses'* file, Walter Macarthur Manuscript Collection, carton 1, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; Peter B. Gill and Ottilie Dombroff, “History of the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific,” typed manuscript, ca. 1942. carton 3, Paul Scharrenberg Manuscript Collection, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, pp. 20 — 23; Averbach, “South of Market," p. 202.

9. Table 43, “Total Males and Females 10 Years of Age and over Engaged in Selected Groups of Occupations, Classified by General Nativity, Color, Conjugal Conditions, Months Unemployed, Age Periods, and Parentage, for Cities Having 50,000 Inhabitants or More: 1900," Twelfth Census of the United States: 1900, 20:720–724; Paul Scharrenberg. “History of the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific,” typed manuscript, ca. 1960, carton 3, Scharrenberg Manuscript Collection. Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, p. 4; Gladys C. Hansen, San Francisco Almanac, rev. ed. (San Rafael, Ca., 1980), p. 74; Weintraub, Andrew Furuseth, p. 8.

10. Averbach, “South of Market”, pp. 203–205; testimony of Paul Scharrenberg and John P. McLaughlin, U.S. Commission on Industrial Relations, Industrial Relations: Final Report and Testimony, 10 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1916), 5:5041,5053—5054; Carleton H. Parker, The Casual Laborer and Other Essays (New York, 1920), p. 80.

11. Sanborn Insurance maps, 1885, microfilm, California Historical Society, San Francisco; photographic collection, California Historical Society, San Francisco; Kate Douglas Wiggin, My Garden of Memory: An Autobiography (Boston, 1923), p. 108; see also Wiggins description of her kindergarten students, pp. 109–126.

12. The 100 block of Tehama has ceased to exist in the redevelopment of South of Market. All that remains is the entrance to the parking lot of the headquarters of the Marine Firemen's Union. The information on the street’s residents comes from 1900 Census Schedules, roll 100.

13. Ibid., supplemented by reference to the Crocker-Langley San Francisco Directory, 1900 (San Francisco, 1900).

14. Crocker-Langley San Francisco Directory, 1900; Wiggin, My Garden of Memory, p. 109; Averbach, “South of Market,” pp. 200—201; Michael M. Zarchin, Glimpses of Jewish Life in San Francisco (Berkeley, 1952), p. 169; Robert McElroy et al., “The Retrospect”: A Glance at Thirty Years of the History of Howard Street Methodist-Episcopal Church of San Francisco (San Francisco, 1883).

15. 1900 Census Schedules, roll 100. For the Palace Hotel, see Oscar Lewis and Carroll D. Hall, Bonanza Inn: America's First Luxury Hotel (New York, 1939), esp. pp. 4, 19 — 29; Guillermo Prieto, San Francisco in the Seventies: The City as Viewed by a Mexican Political Exile, trans, and ed. Edwin S. Marby (San Francisco, 1938), p. 8.

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 3 “Life and Work”