San Francisco Housing Authority and CANE

Historical Essay

by John Baranski

This excerpt originally appeared in "All Housing is Public," Chapter Seven of Housing the City by the Bay: Tenant Activism, Civil Rights, and Class Politics in San Francisco (see below for copyright and book information)

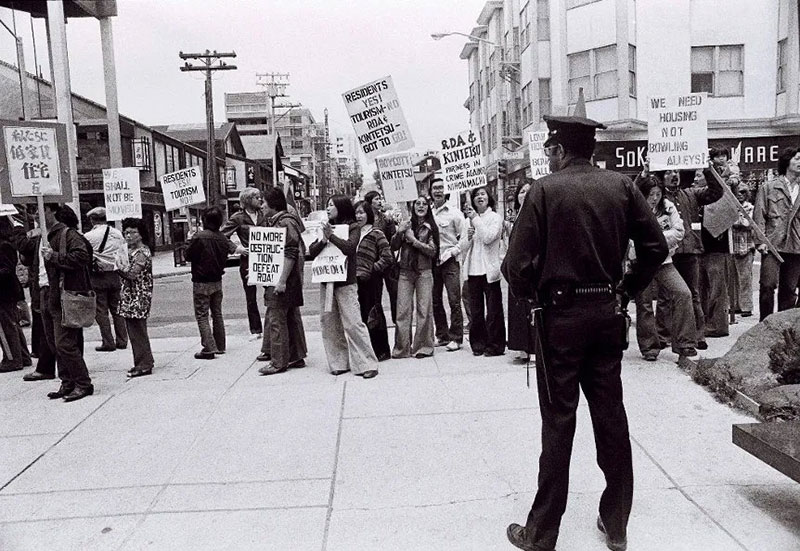

Committee Against Nihonmachi Evictions (CANE) picket line at Post and Buchanan Streets in Japantown, late 1970s.

Photo: J-town Collective, courtesy EastWindzine.com

Residents fighting another wave of redevelopment in the Western Addition also turned to the SFHA. In 1977, the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency began to relocate small businesses and low-income households from Japantown for its Western Addition project. When residents in two residential buildings on Sutter and Buchanan were served eviction notices, the community mobilized to defend the tenants. Unfazed, the redevelopment agency threw tenants out and posted guards at the building’s entrance. The Committee Against Nihonmachi Evictions (CANE) and the Kearny Street Workshop artist collective joined the fight against the redevelopment agency; these groups played important roles in defending the district and contributed to the city’s Asian American movement. Together, the community asked the SFHA for help. In September 1977, a CANE representative described the urgent situation to the SFHA commission and then requested the authority to “take action in the very near future in order to stop the evictions, stop the destruction and end dispersal of the Japanese community.”(20)

At the next meeting, CANE representative Joanne Sheitelman spoke about how the displacement of 2,000 residents from the neighborhood by the redevelopment agency, rising rents, and the long-term effects of World War II internment had reduced the Japanese population and geographic size of Japantown. She noted how the availability of SFHA units had not kept pace with these dislocations and stated that residents would now resist any more evictions.(21)

Japantown resident and CANE member Helen Liveritte speaks out a CANE meeting.

Photo: Boku Kodama, courtesy EastWindzine.com

Redevelopment agency spokesman Gene Suttle then made a presentation. After handing out a package with a history of Western Addition redevelopment, the code violations of the buildings, a list of available housing, and a promise of Section 8 housing to qualifying tenants (not all existing tenants qualified for SFHA housing), he discussed how the elimination of these “dilapidated and decrepit” buildings would improve the district and reduce slums in the city. He observed that the Nihonmachi Community Development Corporation (NCDC) provided the required community participation for the agency’s plans. Suttle closed his presentation by stating that the properties in question were under option and that his agency’s hands were legally tied on the matter.(22)

The next speaker was Randy Wei of CANE. He pointed out that NCDC membership cost $100, and its members focused on “making money” rather than meeting their “higher moral responsibility to the community.” He said “the ‘people’ had been forced out; that Japantown used to extend for 16 blocks and now it is four blocks.” Another speaker, Kris Chen of the Chinese Progressive Association, provided a historical reason why tenants opposed redevelopment. Chen stated that “what was happening in Japantown also happened in Chinatown. They see this as an attempt to disperse the community.” The Chinese Progressive Association, Chen concluded, wanted “the armed guards removed because they are not there to protect” the people and promised to resist “whatever eviction attempts or harassment that will come down on the Nihonmachi community.”(23)

At the next commission meeting, a CANE representative blasted the SFHA, the redevelopment agency, city government, and corporations for their participation in redevelopment and a “pie-in-the-sky proposal of some vague promises” of Section 8 housing. “We are,” the CANE representative noted,

fighting against the destruction and dispersal of the Historic Japanese community as part of the struggle for full equality for Japanese Americans and all Third World and working people. We are fighting for the people’s right to decent low-rent housing in communities that meet their needs. We know that the tenants stand is not just a matter of these two buildings, but like the International Hotel has become a focal point for resisting the city-wide destruction of low-rent housing and dispersal of the communities of Third World and working people.(24)

CANE urged the SFHA to use eminent domain powers to add the two properties to its stock. But the SFHA commissioners did not take over the buildings. As SFHA lawyer Mrs. Harris said, the “agreement between the Redevelopment Agency and the Nihonmachi Development Corporation is a valid, binding contract.”(25)

What was striking about the Japantown and the International Hotel struggles was the way that the city’s residents made claims for housing rights through the SFHA. After two decades of redevelopment and soaring housing costs, low-income residents had few other options. As one woman told Mayor Moscone at a 1977 community forum in Hunters Point, “You ask us, what do you want? Well, we been fightin’ for the last umpteen million years for public housing money, and nobody gives a damn about us.”(26) The SFHA never met demand in the city. But the authority’s ability to keep some low-rent housing under public control was not lost on residents, as these two cases showed. In this way, the SFHA remained one of the institutions used by the city’s residents in their struggle for economic and human rights.

CANE members and supporters on Sutter Street.

Photo: Boku Kodama, courtesy EastWestzine.com

previous article • continue reading

Notes

20. Quote in SFHA, Minutes (September 22, 1977). For CANE and Western Addition redevelopment, see Donna Graves and Page & Turnbull, Inc., “Japantown: San Francisco, California: Historical Context Statement,” prepared for the City and County of San Francisco Planning Department (San Francisco, May 2011).

21. SFHA, Minutes (October 13, 1977); Hartman, City for Sale, 277.

22. Ibid.; “Gene Suttle—Community Leader,” San Francisco Chronicle (September 21, 1995).

23. Quotes in SFHA, Minutes (October 13, 1977). Even Dianne Feinstein worried about insufficient funding for relocating businesses. Letters Between Dianne Feinstein and Carla Hills (June 4 and June 28, 1976), Folder “PRO 16 Relocation,” Box 25 1976, Subject Correspondence, 1966–78, RG 207, NARA/CP.

24. SFHA, Minutes (October 27, 1977).

25. SFHA, Minutes (October 13 and October 27, 1977).

26. Quote in Walter Blum, “Voices from a Forgotten Land,” California Living (magazine of the San Francisco Chronicle and Examiner) (March 20, 1977).

Excerpted from Housing the City by the Bay: Tenant Activism, Civil Rights, and Class Politics in San Francisco by John Baranski, published by Stanford University Press. Used by permission. © Copyright 2019 by John Baranski. All rights reserved.