Saving Grace’s Garden: 30 Years Since the Battle of Filbert Steps

Historical Essay

by Larry Habegger, originally published in The Semaphore #213, Spring 2016

Grace Marchant in her garden, 1980.

“In 1949, when Grace Marchant planted her first pot of the little creeping ground cover known as ‘baby tears’ on the land alongside Filbert Steps, the garden was not only as bare as the cliff face, it was also filled with old bed springs, legless chairs and broken glass. She hauled it all away herself, bringing in soil, shrubs and trees during the 33 years she gardened here, all at no cost to the city.”

—Margot Patterson Doss, “The City’s Magical Hillside,” SF Chronicle, 1/12/86.

Photo: Larry Habegger

“You’ll never win. You don’t stand a chance.”

I still remember this statement from a Telegraph Hill Dwellers’ board member after Gary Kray and I made our presentation asking THD to help us stop a real estate project on the Filbert Steps in 1985. We knew that thousands of people shared our affection for the glorious garden that the late Grace Marchant had created there on what had been a junk-strewn hillside. Beginning in 1949, she systematically cleared the debris from the public right-of-way along the Steps and adjoining properties outside her home and replaced it with an expansive, lush garden. We needed THD’s support to block the demolition of a 1920s-era cottage at 221 Filbert and the construction of a building five times larger that would essentially destroy the garden.

Another statement I vividly remember came weeks later from Lee Gotshall-Maxon, of the law firm Lillick, McHose, & Charles, as we left the hearing at the Board of Permit Appeals on October 16, 1985. Lee is a former college housemate of mine who took on the legal side of our fight pro bono. After the developer went on record that he would be willing to sell his property to the community if the price would “make him whole,” Lee whispered in my ear: “That’s the first crack in the dam.”

Napier Lane Easter Party of 1980: standing left center are Gary Kray and his sister Kim Seibel; seated talking to them is Valetta Heslet, Grace’s daughter.

Photo: Larry Habegger

Thirty years ago, Telegraph Hill nearly lost the famous Grace Marchant Garden. At the time, I had no idea if Lee’s “crack in the dam” offered real hope or just a bump on the road to seeing Grace’s life’s work reduced from a community treasure to an insignificant ornament for one man’s family. But finally, at least, we had a hint of a roadmap for how we might succeed.

By that time our only option was to buy the property from a barely willing seller. And we had no money. And very little time.

The Battle Begins

The conflict started not long after Grace died at age 96 in December, 1982. A two-parcel property overlooking the garden—221 Filbert and 261-265 Filbert—had been sold a year and a half before her death. Early in 1983, Gary Kray, who had trained with Grace and took over custodianship of her garden at her request, heard rumors that the new owner had plans to make some changes. Gary and I were sharing a house on Napier Lane at the time, and had been Grace’s next-door neighbors. Soon we learned that the owner wanted to demolish the cottage and build a new house. Not long after, Gary bumped into community leader and Port Commissioner Anne Halsted at the garden gate. She was showing Supervisor Bill Maher around the area in the interest of resuscitating the drive for a Telegraph Hill Historic District. By the end of their conversation they agreed that it was possible a historic district could prevent the demolition and solve the problem.

The effort to save the garden became entwined with the campaign to create the historic district (which succeeded in December 1986). But over time and several hearings it became clear that getting the historic district in place wouldn’t stop the demolition. So we rallied the neighbors, collected signatures, attended meetings, spoke out at hearings, but succeeded only in obtaining minor delays. Eventually, at a momentous hearing, I thought we had it won. Our neighborhood testimony was compelling; the owner’s lawyer speaking on his behalf stumbled through an inarticulate presentation. I was wrong. The Planning Commission approved the demolition and new construction. Our only hope then was the Board of Permit Appeals.

The Fund-Raising Campaign

We had been through so many hearings (nine by that time) that the “crack in the dam” came about only because the developer was tired of hearing from us. The community had been tenacious, and now he saw a way to shut us down once and for all. He could show good faith, suggest he’d sell, then get the go-ahead to demolish and build when we failed to put up the money.

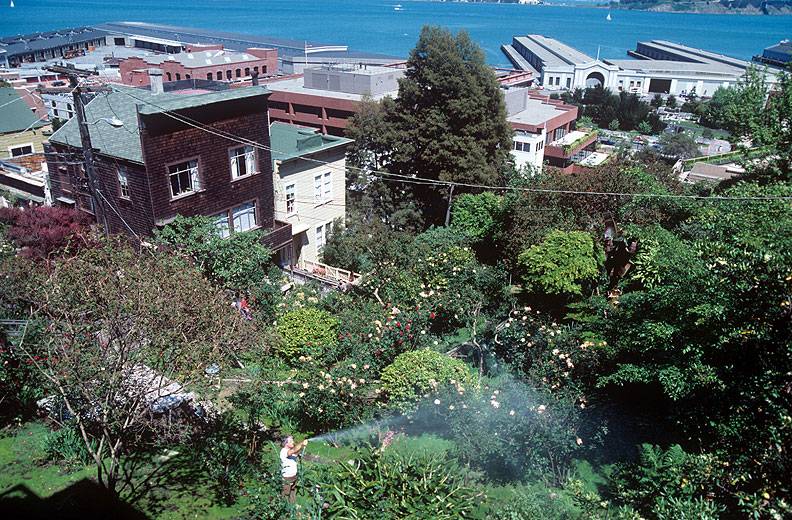

Gary Kray watering the garden, early 1980s.

Photo: Larry Habegger

The sum that would “make him whole” turned out to be $320,000. Today that doesn’t sound like much, but back then, it was a huge amount of money. Bill Maher came up with the notion to talk to Marty Rosen at the Trust for Public Land (TPL). They were based in San Francisco, had dynamic young executives in Jean Driscoll and Thomas Mills, and just might look at this as a feel-good project in their back yard even though they seldom did urban projects. Somehow he convinced them. Real estate lawyer Lee Gotshall-Maxon handled discussions with their legal team, and they came up with the plan to buy the property, put conservation easements on it, then resell the cottage with those restrictions attached so the building would be saved and the garden protected forever.

But the restrictions would reduce the value of the property, so we’d need to raise enough money to cover the difference. Back-of-the-napkin figuring told us we might be able to sell the cottage for $200,000. Further analysis convinced us we needed to raise an additional $160,000 to cover various contingencies.

For our fund-raising effort we named ourselves Friends of the Garden (FOG), which included many neighbors and friends, and then we got started.

I had never raised money, but I was the face of the campaign and took a crash course in fund-raising from ex-officio THD president Jane Winslow and Gerbode Foundation executive Tom Layton. Everyone said the only way we’d attract foundation or corporate donations would be to show significant community participation, that is, cash contributions. We decided on a two-pronged approach.

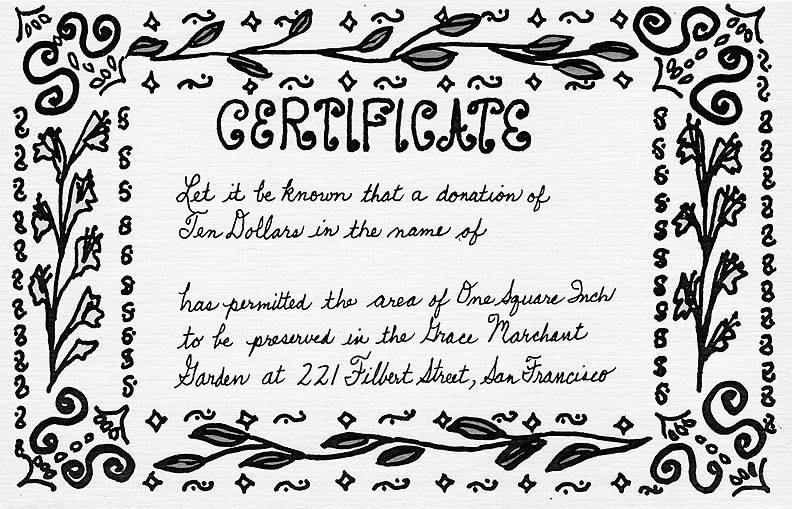

Bryan Holley, TPL’s PR guy, told us about a cool thing they had done once in New York City. They ran a square-inch campaign to raise money in small checks, figuratively selling a property one square inch at a time to willing donors. We decided to try that here. THD allowed us to use their postbox in North Beach. TPL agreed to send out certificates to thank donors (One of the envelope stuffers at TPL was intern Aaron Peskin!).

That was our first prong. The second was to make this a media story. It was the only way we’d be able to raise much money fast. I knew the Chronicle’s Jon Carroll occasionally wrote about gardens, so I sent him our media kit. We’d succeeded in getting Rob Morse out to cover the battle for the Examiner, and I sent him one as well.

A few weeks later, on December 12, 1985, Jon Carroll not only wrote about the garden in peril, he mentioned our need for funds as a good Christmas gift and listed our address. Within a week, about $6,000 and countless letters of support came through the THD P.O. box.

Rob Morse went a step further. He not only wrote about our campaign, he took it on as a cause celebre. Over the next few months he wrote a half dozen columns about it. He shilled for us shamelessly, even apologizing to his readers, but then still asked them to send in donations.

We received editorials in both the Chronicle and Examiner supporting our cause.

Herb Caen, not so sympathetic to us, did mention it twice when things began to turn our way.

Contacts at Examiner Charities, which managed the annual Bay to Breakers race, agreed to sell t-shirts emblazoned with a design by local water colorist Hilda Kidder.

Phil Frank drew Farley cartoons about our square-inch campaign.

We held a $100-a-head fund-raiser at the Washington Square Bar & Grill (that was a very pricey ticket at the time). Marsha Garland corralled the entertainers, headlined by Bobby McFerrin. Mayor Feinstein came. And we sold out the place.

We produced a screening at the Pagoda Palace Theater of the Bogart-Bacall film Dark Passage, which takes place on Telegraph Hill and has a scene on the Filbert Steps, preceded by a slide show of my photographs of Grace and her garden.

Our story got time on all of the local TV news stations and on CNN.

The Board of Permit Appeals continued to wait to see if we could arrive at a deal. And in time we did, in the form of an option to buy the property. This meant we had to put up $25,000 that we would lose if we failed to exercise the option, and we had only until the end of March to do so. It also required us to agree to drop all appeals and resistance to the demolition and new construction should we fail to exercise the option, which, of course, required us to raise the money.

To come up with that $25,000, we obtained $2500 pledges from 10 people in the community who agreed that their money would be forfeited if we were unable to exercise the option (we’d been advised not to use any of the money already raised in case we were unsuccessful). As we were closing in on the deadline to buy the option, Lee and I made conference calls to collect the pledges. One elderly fellow, who was known to have memory lapses but had lived in the community for decades, seemed not to remember what we were talking about. We explained again and again.

“No, I don’t think I’m going to do that,” he said finally, then muttered a good-bye and hung up. Lee and I remained on the line, stupefied, suddenly realizing we had to find $2500 that day or the whole battle would be lost.

We did find that $2500, and we bought the option.

The Money Rolls In

Meanwhile, every day I’d stop at the North Beach Post Office and unlock the box to a stack of envelopes. When we made our foundation pitch, Gerson Bakar of Interland and Levi’s Plaza made the first pledge of $10,000. When the campaign hit the media, I’d open the occasional envelope from a foundation amidst the stack from individuals. Here was one from the Wattis Foundation, wow, for $5000! And one from the Goldman Fund for $10,000! One day, when I opened an envelope from the William G. Irwin Charity Foundation, I knew, for the first time, that we were going to succeed. There in my hands was a check for $25,000.

Grace in her garden, 1980.

Photo: Larry Habegger

The money kept coming in as the deadline neared. On a parallel track, the effort to find a buyer for the property once we’d purchased it had its ups and downs, but eventually produced a deal with James and Firouzeh Attwood, residents of Napier Lane. When it became clear that we’d raised the money and would exercise the option, the owner tried to wiggle out of it. But pressure from Supervisor Maher persuaded him that he had to honor the deal he had made. On April 9, 1986, escrow closed. A few weeks later, the cottage was resold. The battle had been won.

Not only had it been won, but we raised enough money to pay off many of the costs and endow the Garden with $20,000 to go toward plants and supplies. All told we raised just under $211,000, a bit more than half from individuals, including about $40,000 from square-inch checks. We are still nurturing that endowment for the Garden’s ongoing needs.

The Garden Today

Grace spent 33 years tending her garden. Gary Kray took over from her and also spent 33 years maintaining and developing it. My wife Paula Mc Cabe and I took over from Gary when he died in 2012 and continue the tradition of unpaid volunteer labor. I still administer FOG for purposes of occasional fund-raising to keep our endowment healthy. Sixty-seven years ago Grace started the Garden. Thirty years ago we saved it. Today, it still draws people from all over the world. And it looks as good as ever.

Adapted by North Beach writer Larry Habegger from a work in progress, “Grace Marchant and Her Famous Garden: A Life on Telegraph Hill.” For more of Larry’s books, see TravelersTales.com.

To help keep the Garden green, send contributions to Northeast San Francisco Conservancy (NESFC), a 501(c)3 organization, 470 Columbus Avenue, Suite 211, San Francisco, CA 94133, or donate at GraceMarchantGarden.com. All donations are tax deductible.

For a partial list of the hundreds of plant species in the garden, visit GraceMarchantGarden.com. It still draws people from all over the world. And it looks as good as ever.