To Contain or to Conceal: San Francisco’s Plague Epidemic, 1900

Historical Essay

by Eva Knowles, 2021

Men with axes standing in debris of wooden buildings during the demolition of Chinatown.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

| In 1900, bubonic plague broke out in a San Francisco characterized by intense anti-Asian racism and government collusion with business leaders. City government’s handling of the plague hinged on these social, political and economic motivations, resulting in a campaign of concealment and hostility towards Chinatown rather than strategic containment. Though now over a century ago, this event speaks to the continuing relationships between public health, racism, and business. |

As the greater United States stepped into the twentieth century optimistic for a bright and modern future, San Francisco found itself in an age-old nightmare. Few would have expected that the bubonic plague, an infectious disease typically carried by rodents, would once again appear in cities across the world. While known most infamously as the Black Death that had devastated medieval Europe, Asia, and Africa, bubonic plague resurfaced in the 1870s in the Yunnan province of China, from which it began to circumnavigate the globe. Its emergence in San Francisco in 1900 prompted a frenzy of conflicting efforts to stop both the spread of disease and the spread of news. San Francisco’s response to the bubonic plague outbreak of 1900 was impacted by political, economic, and social tensions; it was the combination of anti-Asian racism and illicit attempts to protect commerce and tourism that led to discriminatory policies targeted at the city’s Chinese population as well as widespread denial of the plague’s existence.

Prior to its arrival in San Francisco, the plague had already left mass devastation in its wake. Over the course of five years, ten million people in China died, and another five million were to lose their lives in outbreaks across Northern Africa, Australia, India, and Scotland by the end of 1910 (1). Doctors across the world were ill-equipped to deal with the problem, as there was not much known about the spread of plague. Public health officials and scientists were traditionally distrusted, and the lack of adequate scientific knowledge about medicine and transmission led to a reliance on often useless experimentation (2). As the bubonic plague spread across Asia, United States public health officials were correct in their fear that it was only a matter of time before it arrived in Pacific ports. Two cases were reported in Honolulu’s Chinatown in December of 1899. White officials responded by destroying Chinese-American homes. Ten thousand residents were quarantined in an 8-block area, which was then burned by officials, who called it “fighting the devil with fire” after a white teenager was infected (3, 4). Then, on March 6, 1900, the plague appeared in San Francisco, found in a dead Chinese laborer named Wong Chut King in a Chinatown basement.

Scapegoating Chinatown

San Francisco had a long history of anti-Asian racism, especially when it came to public health. West Coast Asian-Americans, and especially Chinese-Americans, had been treated as medical scapegoats since the 1860s (5). Those in power were quick to fall back on the widely-circulated argument that the Chinese were unhygienic and spread disease, endangering the general population. To learn more about the discrimination that caused the creation of Chinatown and that Chinatown itself continued to experience, particularly during outbreaks of disease, read this FoundSF article by historian Joan Trauner.

This historically-present racism kindled a demeaning and violent response toward the Chinatown population when the bubonic plague arrived in San Francisco. An official quarantine was placed on Chinatown on March 7, the day after plague was identified, in an attempt to stop Chinese-Americans from coming into contact with white San Franciscans. Although the quarantine was lifted on March 9, the area was heavily monitored, guards were stationed at all exits to examine those coming and going, and Chinese-Americans were banned from transportation altogether (6). Residents of Chinatown were also subject to forced vaccination, often involving an experimental vaccine using plague cells from cadavers (7). A short-lived executive order under William McKinley required Chinese- and Japanese-Americans to carry a certificate of vaccination in order to leave the state; however, this was declared in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment (8). Forcible house-to-house inspections were conducted by policemen and medical volunteers to locate victims of the plague and unsanitary conditions. They used chemicals like sulfur dioxide and mercury bichloride to disinfect homes, aired household goods in the streets for one to three days, and whitewashed basements. Despite their efforts, they were unable to find many victims, in part due to many Chinatown residents supporting concealment because they didn’t want the plague to serve as justification for additional discrimination (9). In addition, some feared that San Francisco’s Chinatown might be burned like the Chinese quarter in Honolulu if plague cases were to rise. They were not incorrect, as many health authorities and newspapers alike suggested that Chinatown should be destroyed altogether. The San Francisco Call maintained that “so long as it stands so long will there be a menace of the appearance in San Francisco of every form of disease, plague and pestilence which Asiatic filth and vice generate” and advocated to “clear the foul spot from San Francisco and give the debris to the flames” (10).

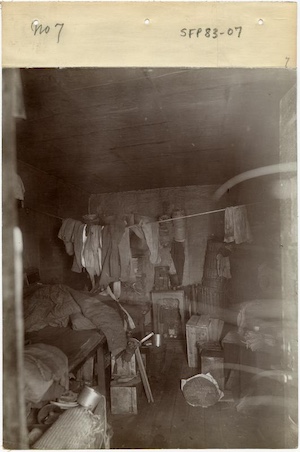

Interior of living quarters in Chinatown prior to the outbreak of plague.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Meanwhile, the argument that the plague was “an Oriental disease, peculiar to rice-eaters” created conflict over whether it was legitimately dangerous (11). With not much known about transmission, medical theorization was linked to social prejudices rather than science. Plague and other diseases were believed to be largely racial as the majority of those infected during the 1900 epidemic were of Chinese descent. However, the spread was not a result of race, diet, or other characteristics blamed by the government and medical organizations. Instead, it was likely due to the fact that Chinatown was San Francisco’s most impoverished and crowded neighborhood. Neglect and discrimination by public officials and the presence of disease formed a vicious cycle. While it is true that measures such as the quarantine and disinfection process were taken, public officials were much more hesitant to take preventative measures than they would have been if it had been the white population, rather than the Asian and Asian-American one, that had been affected most acutely. Predictably, the disease would be taken more seriously once it claimed white victims (12).

Plague Loves Corruption

In addition to the identification of an easy scapegoat for plague, the corrupt political sphere of San Francisco would provide a perfect breeding ground for the uncontrolled spread of disease. At the turn of the twentieth century, San Francisco was the richest and most prominent Pacific port due to trade with Asia as well as the rest of the United States. It was considered the cultural and financial capital of California and was well on its way to becoming one of the most important cities in the nation. However, the city’s Gold Rush history had cemented a strike-it-rich mentality—or a belief in fate rather than hard work and in greed rather than generosity—into local politics (13). The local government was known by San Francisco residents to have a history of corruption. Government officials, coerced by local elites and businessmen, did not invest time nor resources into improving living conditions for the general public. The city was notoriously dirty and overcrowded; officials were not willing to spend money on sanitation or medical care at the expense of private wealth. In fact, public health-related spending fell significantly as the population grew (14).

With the arrival of the bubonic plague, these ties between the political and economic worlds were exposed: city- and state-level politicians, in collusion with business leaders and the press, worked to deny the plague’s existence in order to protect commerce and tourism. With a reputation to uphold, business leaders feared embargoes by neighboring states and other countries. San Francisco was in the middle of an economic boom, so diverting trade to developing cities like Seattle, Los Angeles, and Vancouver could hurt expansion. In the words of one historian, “business and capital, always timid and jumpy, were fearful of sick rats and Chinamen” (15). Newspaper editors were persuaded to keep a blackout on reports of plague, denouncing rumors as fake and drawing on existing mistrust of public officials. Newspapers ran stories claiming that the plague either did not exist or did not pose a risk to the general public. For example, The Bulletin claimed that the plague was dangerous only to the economy, as it diverted tourists and cargo from the port (16). On March 8, 1900, The San Francisco Call published a front-page story called “Plague Fake is Part of a Plot to Plunder,” beginning with the decisive statement “there is no bubonic plague in San Francisco” (17). These articles echoed the public’s suspicion that reports of the plague were being used as a way to acquire financial assistance for the underfunded health department; the Call article also described how the plague was a way to “plunder the funds of the taxpayers” (18).

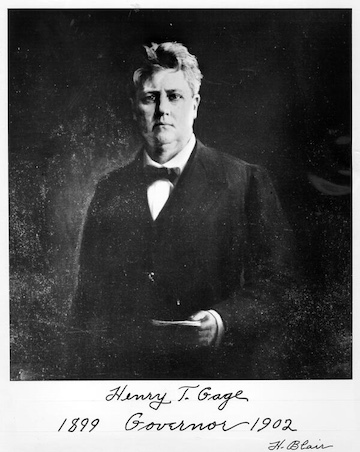

California Governor Henry Gage was among those who denied the existence of the plague in California, using his power to obstruct all attempts at prevention methods. When a federal commission confirmed the existence of the plague in 1900, Gage saw it as an insult. President McKinley, who didn’t want to risk alienating him, agreed to negotiate a compromise. The commission wouldn’t publish their results, and in exchange, California would support a federally directed cleanup of Chinatown. Gage agreed to spend $25,000 on fumigation and disinfection as well as the construction of a crematory, laboratory, detention barracks, hospital, and morgue. However, he continued to assert that “San Francisco is and has been absolutely free from the disease, and… those who said it existed were either mistaken or deliberately misrepresented the facts” (19). When the federal report of plague was leaked to the press in 1901, San Francisco residents criticized the way that Gage and the Department of the Treasury had chosen business over public health. At the same time, those who pushed for recognition of the epidemic, such as the leader of the port’s Marine Health Service Joseph Kinyoun, were demonized by politicians and business leaders alike, and especially by Governor Gage. Kinyoun had a strong education in the science of plague and was appointed to his position specifically to protect against it. However, Governor Gage accused him first of incompetence and then of inoculating corpses with plague bacilli, leading to Kinyoun’s brief arrest and his transfer from the city. Over time, Gage’s efforts to conceal the bubonic plague’s existence became more and more futile as news reached the far corners of the nation. His extreme stance alienated even his own Republican Party, costing him reelection.

Henry Gage, 20th Governor of California (1899-1903).

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Gage’s fate spelled out the future of plague denial; as word spread across the country and new government officials took charge, attempts to conceal the plague were ultimately unsuccessful. Recognition of collusion between politicians and business leaders sparked an uproar. In November 1902, the New York Times ran a story on San Francisco’s corruption, declaring that “it is said the business men of San Francisco have used their influence to keep the health authorities from publishing the facts in regard to the cases that have occurred and in this way have aided in the spread of the disease” (20). Then, in January 1903, delegates from more than twenty states threatened to quarantine California if further measures weren’t taken, condemning the California State Board of Health for a “gross neglect of official duty” (21). The Board finally agreed to comply with recommendations for an eradication plan when states warned they would boycott trade.

People pulling down a wooden building during demolition of Chinatown.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

An End to Plague?

Harmonious action from the chamber of commerce, the Merchant’s Association, the federal Marine Hospital Service, and new California governor George Pardee – a doctor – allowed for a successful, while still largely discriminatory, plague campaign. Despite a changing attitude surrounding science and the role of the San Francisco government in defending public health, views toward Chinese-Americans had not shifted, and it was predictably the Chinese population of the city that ultimately bore the brunt of the eradication of disease. Assistant Surgeon Rupert Blue called for the cleansing and rat-proofing of Chinatown using traditional methods such as fumigation with sulfur. His team also destroyed old buildings and tunnels in addition to replacing wood floors with cement ones, affecting three hundred homes (22). He also used less traditional methods, such as a focus on eradicating the disease in rats rather than only in humans, noting in his plan the importance of “the destruction of rat habitations as far as possible; the abolition of the means of rat sustenance; and the protection of all places of human residence against the ingress of rodents” (23). The last official case of bubonic plague of the epidemic was reported on February 19, 1904. In total, 121 cases were documented, although this count was likely too low, as it did not include those that were deliberately concealed.

Debris from wooden buildings during the demolition of Chinatown.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

While the bubonic plague outbreak of 1900 was ultimately contained, it had exposed a social plague of racism and corruption whose legacy would carry through to the present day. The epidemic contributed to a tradition of blaming non-white people and immigrants for problems faced by their cities, states, and the nation. For instance, when the plague appeared in Los Angeles in 1924, the Latinx population was treated similarly to San Francisco Asian-Americans; 2,500 Mexican-Americans were quarantined, many were fired from jobs, and homes were burned down (24). The epidemic also revealed the self-serving motives of the business community, politicians, and the press that have also appeared amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Some politicians have advocated to prioritize the economy at the expense of public health, downplaying the danger that the pandemic poses. At the same time, Asian-Americans have been commonly blamed for the spread of COVID-19 – often derogatorily referred to as “kung flu” and “China virus” – resulting in widespread anti-Asian sentiment and hate crimes. Stop AAPI Hate reported 3,795 accounts of hate against Asian-Americans between March 19, 2020, and February 28, 2021, 44.6% of which were from California (25). In the end, the chaotic and often inequitable handling of the bubonic plague epidemic of 1900 was not an isolated event. Instead, it was informed by legacies of racism and ties between business and government, serving as just one more piece of evidence for the danger of intertwining medicine with unjust social, economic, or political motives.

Notes

1. Randall, David K. Black Death at the Golden Gate: The Race to Save America from the Bubonic Plague. W. W. Norton & Company, 2019. eBook file.

2. Ibid.

3. Barry, Rebecca Rego. “San Francisco's Plague Years.” Science History Institute, September 10, 2019. Accessed January 27, 2021.

4. The Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu, HI). “The Board of Health.” January 1, 1900.

5. Trauner, Joan B. “The Chinese as Medical Scapegoats in San Francisco, 1870-1905.” California History 57, no. 1 (1978): 70-87. Accessed January 27, 2021.

6. Ibid.

7. Barry, 2019.

8. Ibid.

9. Risse, Guenter B. “‘A Long Pull, a Strong Pull, and All Together’: San Francisco and Bubonic Plague, 1907-1908.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 66, no. 2 (1992): 260-86.

10. The San Francisco Call (San Francisco, CA). “Clean Out Chinatown.” May 31, 1900.

11. Trauner, 1978.

12. Ibid.

13. Randall, 2019.

14. Ibid.

15. Trauner, 1978.

16. Lawler, Andrew. “When bubonic plague first struck America, officials tried to cover it up.” National Geographic, April 24, 2020. Accessed January 27, 2021.

17. The San Francisco Call (San Francisco, CA). “Plague Fake Part of a Plot to Plunder.” March 8, 1900.

18. Ibid.

19. California State Board of Health, Report of the Special Health Commissioners appointed by the governor to confer with the federal authorities at Washington respecting the alleged existence of bubonic plague in California: also report of State Board of Health., A. (Cal. 1901).

20. Special to The New York Times. “The Bubonic Plague in San Francisco.: Menace to the Country Because of the Carelessness of the Health Authorities of That City.” New York Times (1857-1922) (New York, N.Y.), 1902 Nov 03, 9.

21. Treasury Department - Public Health and Marine Hospital Service. “Public Health Reports: Plague Conference Continued.” Public Health Reports (1896-1970) 18, no. 6 (February 6, 1903).

22. Risse, 1992.

23. Blue, Rupert. “The Conduct of a Plague Campaign.” Journal of the American Medical Association, February 1, 1908, 327-29.

24. Barry, 2019.

25. Stop AAPI Hate, comp. Stop AAPI Hate National Report. March 16, 2021. Accessed May 29, 2021.