Wheat King: Isaac Friedlander

Historical Essay

by Felix Reisenberg, Jr.

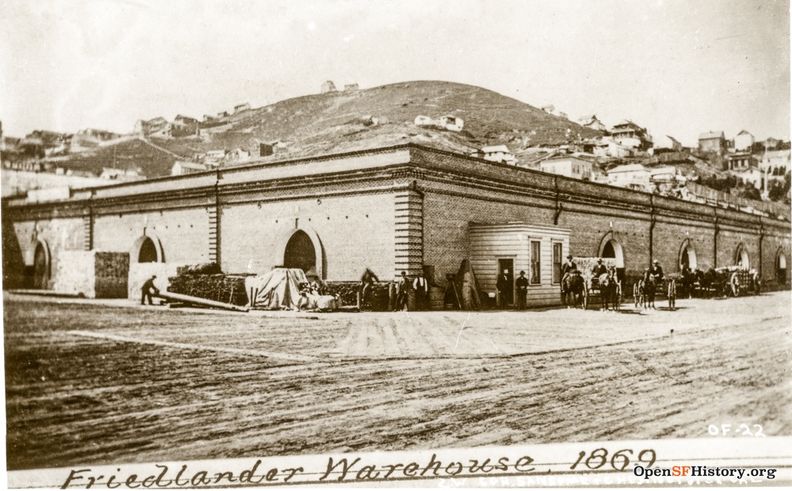

Friedlander Warehouse, 1869, on southwest corner of Sansome and Chestnut, Telegraph Hill rising up behind.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp27.3812

Through the eighteen-sixties, into the ’seventies, the grain trade was dominated by one man, a big German immigrant, Isaac Friedlander, who came to San Francisco near the start of the gold rush as a young greenhorn. Like many who emerged from the crowds, he left the digging of gold to others and made plans for getting it second hand.

After being in business on Yerba Buena Cove for a time Friedlander, along Rogers, Meyer & Company and other merchants, showed interest in the San Joaquin Valley, where more and more wheat was being grown. His name was one of a distinguished list backing the California Canal and Irrigation Company, a project designed to increase the output of grain when the European demand became great. The “Wheat King” was a tall (6’7”), stooping man with a narrow face, prominent nose, and very white skin. Dressed in a Prince Albert coat, wearing a stovepipe hat, he towered above other traders in the street where grain charters were made amid a bedlam of noise. The girl from South Carolina whom Friedlander married made his home noted for its hospitality; Mrs. Friedlander’s seventeen-course dinners placed her and Isaac among the leaders of South Park society.

Friedlander was not a shipper of wheat himself, for the export trade was then largely in the hands of foreign firms whose representatives received orders from abroad. Friedlander supplied the wheat and ships in the execution of orders.

Farmers grew resentful of this system and of the general overseeing of San Francisco capitalists, which they believed robbed them of proper profits. They had already organized into the “Patrons of Husbandry” to combat discriminating railroad rates and in 1872 began what was called a “granger movement” to eliminate the middleman from grain shipping. In groups, the “granges,” they chartered their own ships and sent wheat direct to tidewater for loading. The movement looked so promising that E.E. Morgan’s Sons of New York, a firm with extensive connections abroad, sent one of its smartest young men to San Francisco. This was a Mr. Walcott, who arrived with an almost unlimited letter of credit and set about cornering the Pacific tonnage market. He listed the position of ever ship in the world likely to be on the range during the wheat export season and arranged to have many others diverted to the Golden Gate. Friedlander answered the challenge. There began the most spectacular fight for ships that the port had ever witnessed.

Isaac Friedlander, oil portrait, 1878, not long before he died of a heart attack.

Photo: Wikimedia commons

The harvest year of 1872-73 was chosen for the inauguration of the new movement. The prevailing rate up to that time, sixty shillings per ton, was considered high. Operators feared it would drop with the converging of ships on San Francisco. But the European demand was immense, and before the last of the fleet of three hundred and thirty-eight vessels cleared, the average had jumped to sixty-five shillings, the highest ever obtained for grain charters at San Francisco. Everyone, except ship operators, lost money; Friedlander was dethroned as Wheat King. After crop failures in 1877, he died of an apparent heart attack in 1878.

Rates continued high through the next decade, when Friedlander was succeeded by George Washington McNear, a former shipmaster who built big docks at Port Costa and shipped much of the million tons of grain which went round Cape Horn in 1880. New American ships came to lie at Green and Vallejo street wharves or cockbilled their yards to come alongside Mission Rock: the A.J. Fuller, Commodore T.H. Allen, Tacoma, E.B. Sutton, S.P. Hitchcock, and the few of the great Sewell steel ships.

1859 U.S. Coastal Survey Map, showing Mission Rock well out in the Bay.

The rock was bought and sold a number of times and eventually settled into a long life as a grain terminal.

Men working cargo on Mission Rock, 1897. Yerba Buena Island barely visible in distance.

Photo: San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park (A11.22,404n)

Originally published in Golden Gate: The Story of San Francisco Harbor by Felix Reisenberg, Jr., Tudor Publishing Co., New York: 1940