Uses of Market Street

Historical Essay

by Erick Lyle

Westerly view from Hewes Building at 6th and Market, 2005.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

To walk down Market Street today is to find oneself slipping in and out of time. Here, the great speedup of our digital era meets the medieval as one encounters a vast population of homeless people, many of them sleeping nightly on the streets in front of empty buildings that have been vacant for decades.

The clear-eyed flaneur on Market Street might well conclude that civil society has at last broken down completely. Yet the gritty reality of the street has lately become indistinct, difficult to bring into focus. What once may have been understood as a humanitarian crisis has been rebranded as “The Tenderloin Arts District.” Hallucinations of luxury hotels and shopping malls crowd the street as the past slowly dissolves into the future.

Conservative mayoral candidates and newspaper publishers with their perennial calls to “Clean Up Market Street” appeal to nostalgia for a kind of civic consensus that in real life has never truly existed. Indeed, the cable car slot in the center of Market Street was for generations seen as a literal border between the upper classes from the hills north of Market Street and the poor homesteaders on the flats “South of The Slot.” I wonder if it is accurate after all to say that there is a city comprised of these competing realities, these alternative futures, so much as it is to say that there are only these alternative futures, and that the place where they stage their perpetual battle is what we call the city. Either way it is certain that Market Street has never really been a “Main Street” for everyone so much as the border where San Francisco’s competing realities collide.

Perhaps no writer has made greater use of the San Francisco’s embrace of alternative futures than Philip K. Dick. His 1962 novel, The Man in the High Castle is a mind-bending masterpiece, set in the parallel universe of fascist San Francisco, fifteen years after the Nazis and Japanese have won World War II. Midway through the book, Dick introduces a book within the book—a popular novel, banned by the Nazi authorities, though widely read in secret in the conquered USA—in which a mysterious author has conjured up a fantasy alternative world. In this underground novel, the United States and England persevered to defeat the Axis Powers. As characters read the banned book, they become unstuck in time, wandering in uncertainty between competing realities.

Dick’s novels are often set in a San Francisco of the future, a familiar city made strange to us by technology and the passage of time. While on the surface they appear greatly changed, Dick locates within these futuristic cities something deep and true about San Francisco—a city sometimes comforted and sometimes haunted by but always in turmoil with its own competing realities.

Putting a Boulevard Through the Dunes

A couple of years before the discovery of gold near Sacramento in 1849 would bring thousands of new settlers to the area, San Francisco was still Yerba Buena, a tiny hamlet of around five hundred people, centered around today’s Chinatown area. A young Irish civil service engineer named Jasper O’Farrell was hired by the military mayor to plot a grid of streets for a future city. O’Farrell, situating his street plan further to the north of the actual settlement, drew a diagonal line from the waterfront directly west toward Twin Peaks and called it Market Street.

The Market Street that O’Farrell proposed for the virtually uninhabited settlement was an incredible 120 feet wide—a full twenty feet wider than its namesake back east in Philadelphia. The proposed right-of-way of this grand boulevard, however, was blocked by a sixty-foot tall sand dune roughly at the site of today’s Palace Hotel. Miles of sand, including dunes reaching ninety feet tall, stretched further west in the future street’s path toward the ocean.

O’Farrell, with his arbitrary line, would thus mark the debut of the concept of “Market Street”—the idea that the future city, not even yet named San Francisco, must be built around a grand boulevard, suitable for both military parades and shopping trips. Property owners, who felt O’Farrell’s future main street would infringe on their land, organized a lynch mob, and O’Farrell fled the Bay Area, never to return. But his grand Market Street was built across the sands anyway. San Francisco has been trying to figure out what to do with it ever since.

Market Street cutting through the city, as seen from Twin Peaks, 2014.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Perhaps Market Street has never quite been a main street for the San Francisco we see today because the street was not built to scale with the rest of the city, but instead to the specifications of a lost imaginary San Francisco. This ghost city—planned and mapped and deeply longed for, but never built—has always closely shadowed the actual city. Market Street, and San Francisco’s similarly outsized City Hall, can be seen as strange archaeological relics of that lost city that survive today, as if unstuck in time, from some parallel San Francisco in which the Nazis won the war.

By the time the nineteenth century drew to a close, San Francisco was the largest city on the west coast, swollen with money and plunder from the gold fields of the Sierra Nevada and the silver mines of the Comstock Lode in Nevada. City leaders often compared the city to ancient Rome, and war veterans and military bands frequently paraded down Market Street in imperial style. When the United States annexed California from Mexico, city leaders positioned San Francisco as the capital city of what they saw as the inevitable onward flow of manifest destiny across the Pacific. The president of the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce declared, “The nation that shall control the business of Asia will control the world.”

In 1898, a mysterious onboard explosion sank the US battleship Maine in the Havana harbor in Cuba. Though we now know that the explosion was caused by a faulty boiler that blew up, Western capitalists and politicians saw in the flames a perfect opportunity for imperialist expansion. William Randolph Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner inflamed public opinion in favor of a war with Spain. The quick military victories over Spain in Havana and Manila gave the United States its first colonial possessions—Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. Even as reports began to spread of US soldiers torturing captured Filipino guerrillas in jungle concentration camps, San Francisco Mayor James D. Phelan erected the Dewey Monument in Union Square to commemorate Commodore Dewey’s handy capture of Manila Bay. The monument depicted the winged Goddess Victory, facing west into the Pacific.

Mayor Phelan and other leaders imagined that with US seizure of the Philippines and more interventions sure to follow, the city would at last fulfill its Roman destiny. Accordingly, architect Daniel Burnham announced a plan to redesign the city along the lines of Baron Haussmann’s redesign of Paris under Napoleon III, cutting many new and grand Market Street-style boulevards through the city and extending Panhandle Park down to City Hall. Historian Grey Brechin, in his book Imperial San Francisco, describes how Burnham’s proposals exemplified the era’s hubris:

“San Francisco’s cheap frame structures would be gradually replaced with monumental buildings of masonry. One-third of the city’s area should be devoted to parks serving an anticipated population of 2 million, while prominent hilltops would be given to monuments honoring the pioneers. Phelan’s projected aqueduct from Hetch Hetchy Valley would eliminate past restrictions on greenery, feeding lawns, and fountains worthy of Versailles… A colossus representing San Francisco would gaze west from Twin Peaks to the city’s future in the Pacific, while an immense drill ground inside Golden Gate Park would permit tens of thousands of civilians to cheer the precision movement of troops and warships on review.”

Instead, a few short years later, the city planner’s imperial dreams would be reduced to rubble. The Great 1906 Earthquake and subsequent fire leveled 4.7 square miles, or 508 city blocks, while destroying 28,188 structures, including City Hall, the Hall of Justice, the Hall of Records, the County Jail, the Main Library, five police stations, and over forty schools.

Following the quake, an epic beaux arts City Hall was built according to Burnham’s plans. Its dome, encrusted with twenty-four karat gold leaf, is still the fifth-largest in the world, a full forty-two feet taller than the US Capitol Building. But Burnham’s other plans for a Roman San Francisco were abandoned in the haste to rebuild a functional city. The city’s population eventually topped out near eight hundred thousand, where it remained for decades, and Los Angeles surpassed San Francisco as the economically dominant metropolis on the west coast.

Post-earthquake San Francisco was like a city that had lost a war. In the famous opening rooftop chase scenes of Hitchcock’s Vertigo, one sees that as late as 1958 a camera could still pan across a San Francisco skyline that featured no skyscrapers.

Today, Burnham’s City Hall, as if beached in the river of time, presides over a city that never realized its early imperial aspirations. The baroque interior now appears charmingly gaudy and decadent, with its gold leaf and marble, its chandeliers and ornate lampposts, and its grand, theatrical staircase. In events that might as well take place in a parallel universe from that the city’s founders imagined, City Hall would reveal what seemed like its fabulous décor’s true purpose all along—in 2004, the area under its rotunda became the perfect setting for the first legally performed gay marriages in the United States.

Skid Row by Design

In her famous early work, The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems, Martha Rosler examined, among other things, the very idea of “skid row.” The work consisted of a series of photographs Rosler had taken while walking along perhaps the world’s most famous such street, The Bowery in New York City. The collection does not include the photos of homeless men one might expect; instead it includes an inventory of their detritus—empty wine bottles, old shoes, crumpled litter. The photos were mounted alongside photographs of words typed on white paper — synonyms for drunkenness like “sodden,” “soused,” “sloshed,” and so on. Rosler’s refusal to present the usual human figures of documentary photography questions photography’s system of representation itself and suggests that such studies might actually perpetuate society’s power structures.

By challenging the representation of The Bowery, Rosler suggests that “Skid Row” — like “Main Street” — is itself a construct. San Francisco redevelopment forces have cynically promoted and manipulated these two twin fantasies of Market Street for generations, forever invoking fears of a nostalgiac “main street” always threatened by an out of control “skid row” in an effort to consolidate their power in the city. Indeed, as the success of the SFRA efforts to remake San Francisco as a city of the rich has led to exorbitant rents and the loss of living wage jobs, the very architects of this transformation point to the subsequent proliferation of homelessness in tourist and business areas agendas as evidence of the progressive left’s inability to govern. While this strategy has again and again elected the more conservative candidate to the mayor’s office, all observers agree that it has not made a dent in the actual homelessness crisis in the Bay Area over the last twenty-five years.

But to solve the problem is not their goal. If it were, building affordable housing and putting a stop to illegal evictions would be a priority. Instead, as the city gives more tax breaks to corporations and green lights the construction of one massive luxury apartment tower after another, each successive mayor simply uses the police to move the homeless encampments strategically around town, keeping them out of sight of the new zones of development and property-value boom. The problem is always said to be improving — except when it isn’t. At election time, homelessness inevitably becomes a crisis again, more evidence of how the permissive Left has allowed the city to disintegrate out of control.

After living for almost a decade on Market Street and in the Tenderloin, I can only agree that Market Street is a broken or failed civic space. But my proximity also allowed me to see, up close, the ways conservative politicians and property owners manipulated and indeed perpetuated that situation for their own gain. While the crisis of “what to do with Market Street” is a real one, it has also been—like the city’s homeless problem—heavily stage-managed.

949 Market Street

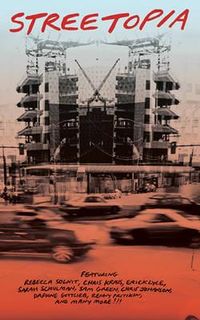

Excerpted from Streetopia, in the essay "The Uses of Market Street"