Twin Peaks Falls: Battle of Vista Francisco

Historical Essay

by Devin Smith

Originally published in OutsideLands.org

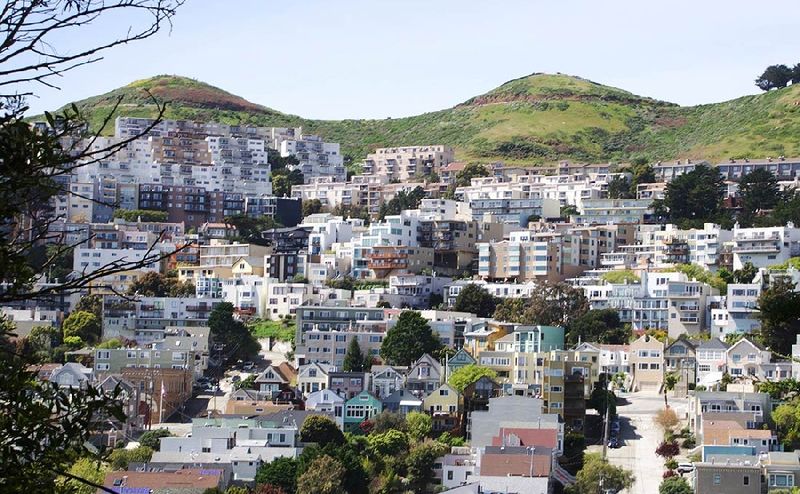

View west to Twin Peaks and the Vista Francisco apartments development., 2017

Photo: David Gallagher

How the Standard Building Company covered 21 acres of the east side of San Francisco's Twin Peaks with apartment buildings.

Twin Peaks is, in some ways, like a small mountain town dropped right in the middle of San Francisco—the city’s equivalent of a flyover state (tunnelunder state?). It’s basically nonexistent in online culture writing, because there's no action up here. No storied music venues. No overhyped foodie spots. No upstart tech companies burning through VC cash, salacious hubris-and-downfall sagas in the opening chapters.

Like most simple questions, “What exactly defines a neighborhood?” is the first step into an endless philosophy deathspiral. “Twin Peaks,” in the broad sense,(1) is comprised of three smaller neighborhoods circling the mountain: Clarendon Heights to the north, Midtown Terrace to the west, and Twin Peaks proper to the east (which some maps elide into Upper Market).

But as similarly sleepy as these three neighborhoods are, they’re markedly different in character…and these differences trace all the way back to when they were carved out of the mountain.

After centuries as a lookout spot for the Ohlone, Twin Peaks entered the development record as the northern tip of the massive Rancho San Miguel granted to Don José de Jesùs Noé, the last alcalde of Yerba Buena. Back then, the mountains were grassy pastureland; Noé sold the land containing Twin Peaks to Adolph Sutro, who planted the eucalyptus trees during an Arbor Day campaign. An 1885 photograph captures the waist-high saplings twisting ambitiously towards the clouds.

Around this time, the first Victorian estates (and curious DIY castles) began to rise on the northern slope of the mountain, branching eastward from Market Street. Clarendon Heights grows from this pedigree, and today, as a collection of mismatching mansions and secret brick stairways, maintains something of its original contrarian nouveau riche character.

Midtown Terrace arrived all in one go. Built from 1953–1960, it’s a textbook postwar planned community of single-unit detached houses snuggled into a basin in the foothills. It was designed for new mid-income families during the Baby Boom, and this is largely the demographic which still lives here today: the percentage of kids is more than double San Francisco’s average.(2)

Midtown Terrace flies under the radar. It remains hidden behind hills and groves; until you walk its Oldsmobile-size blocks on foot, it's hard to get a feel for how big it actually is. Wandering up and down the curvy avenues—lined with faded pastel houses tucked into stands of fragrant eucalyptus in the fog—can feel a little like strolling into a midcentury suburban Brigadoon. Picture me doing my best Cyd Charisse Heather on the Hills choreo along the sloping sidewalks.(3)

・ ・ ・ ・ ・

But in order to tell the story of the neighborhood on the east side of Twin Peaks, we’re going to have to back up a bit and introduce Carl and Fred Gellert, the brothers at the helm of the deceptively banal-sounding Standard Building Company. Starting in 1922, the Gellerts took Standard from building small homes, up through apartment buildings and commercial space, to tackling entire subdivisions (starting with Ardenwood in 1932).

They struggled through the Depression, but as the market picked up at the end of the ’30s, they built huge swaths of row housing in the Sunset, under the optimistic brand name Sunstream.(4) Housing construction was diverted during wartime, but Standard was perfectly positioned to catch the postwar boom.

Fred focused on the construction, while Carl handled the business side; eventually becoming a heavyweight in major trade organizations. He served as chairman of the Building Industry Conference Board, and was the Lifetime Director of the National Association of Home Builders. By the mid-50s, Standard was arguably the most important single-family home developer in San Francisco.

But… Carl Gellert also took no issue with exclusionary housing policies. While it was still legal, many of Standard’s developments included racial covenants specifying only whites could purchase homes.(5) After California’s landmark anti-discrimination law, the Unruh Act, passed in 1959, their salesmen found workarounds, like simply leaving the model homes when nonwhite prospective buyers stopped by.

Willie Brown (then a lawyer on the rise) kicked off one of San Francisco’s first sit-ins in exactly this circumstance. On a bright May afternoon, Brown and two colleagues waited patiently in an empty, sparkly-new Standard home after the salesmen had fled—a guard was sent to lock up at the end of the day. The activists returned and bolstered their numbers day after day…as Standard’s salesmen nervously circled the block, and peeked from behind the curtains of a nearby house.(6)

Lakeshore Park? Inverness? Country Club Acres? Standard built all of those. And Midtown Terrace? Standard built that, too. And while they were planting tidy rows of suburban houses on the western slope of the mountain, they turned their attention to the east, where they owned around 21 acres of land which, to this point, was still mostly wild.(7)

・ ・ ・ ・ ・

Which brings us to the rather unusual Board of Supervisors meeting on October 19, 1959. On the docket was the final approval for an ordinance which had been twelve years in the making: updated zoning maps covering literally every parcel of land in San Francisco. During this session, the supervisors voted to add five last-minute amendments—Stopping frequently to confer with various lobbyists in the antechambers…among them, Standard Building Co.’s attorney, Albert Skelly.

One of these amendments re-zoned Standard’s 21 acres on Twin Peaks from single-unit detached housing to apartment complexes. It passed in a 6-4 vote. Journalists in the room noted an odd turn of phrase during Supervisor Joseph Casey’s presentation in support of this re-classification: he referred to “the damage we would suffer if this amendment was not passed.”(8)

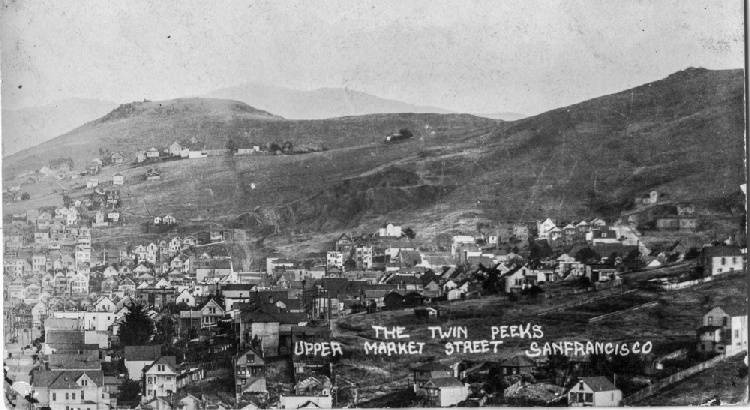

View south from Corona Heights to Noe Valley (The Twin Peaks, Upper Market Street), circa 1910

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp27.1338.jpg

Two days later, the San Francisco News-Call Bulletin broke the story. In the weeks leading up to the vote, Standard had made large campaign donations to five of the six “Yes” voters—circumventing the normal procedure of anonymizing donations,(9) and informing the supervisors directly by phone. Casey’s presentation was, apparently, a direct appeal penned by Standard.

The public and (more pertinently) the politically-influential neighborhood associations were outraged; some of the Planning Commission’s original zoning recommendations had been informed by years of public hearings and input.(10) A Grand Jury investigation was launched, and the supervisors hastily called another session to re-vote the amendments.

Still, without a smoking gun quid pro quo, it wasn’t entirely clear that Standard’s money had influenced the votes. The mayor voiced his support for the supervisors, and during the re-vote, they reversed course on only one amendment, the others—including the multi-unit zoning on Twin Peaks—remained.

As Supervisor Charles A. Ertola commented during the fallout, the “maybe $200” he received from Standard “…didn't influence my vote. I'd vote again for an R-3 designation on that land. It's so hilly, it'd be stupid to build homes on it. Besides, the city will get more tax yield from multiple units.”(11)

The Planning Commission and Public Works Department were unwilling to risk another contentious round of voting scuttling their twelve years of work on the zoning ordinance; they accepted the amendments and pressed on. After a few rounds of negotiation over building heights,(12) Standard’s plans for the first half of the new 700-plus-unit Vista Francisco subdivision were approved by the City Engineer and Director of Public Works in early 1962, leaving only a pro forma vote from the supervisors.(13)

・ ・ ・ ・ ・

Jack Morrison was furious. Already notable on the San Francisco political scene for his work in the nascent wave of urban environmentalism organizations, he was running for supervisor when the re-zoning fracas popped off.(14) He lambasted the sitting supervisors for having “bowed to the will of the lobbyists for Standard,” and referred to the development as “the rape of Twin Peaks.”(15)

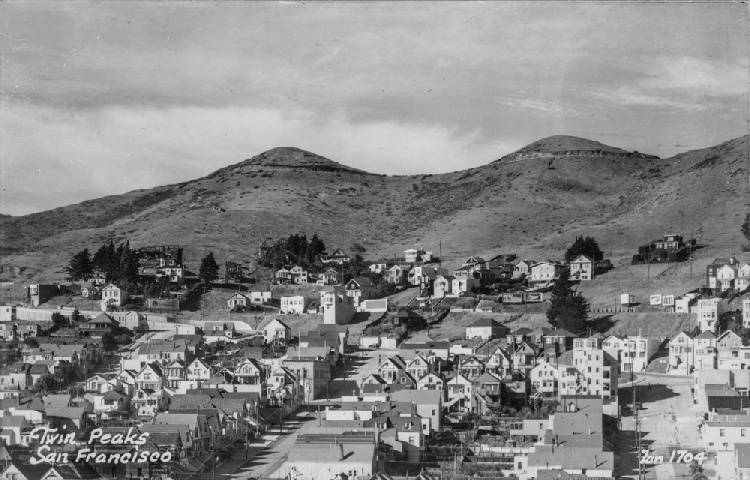

Photo postcard view west to Twin Peaks from 22nd and Noe Streets., circa 1925

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp27.3324.jpg

After his failed 1960 run, when Morrison was elected to the Board for ’62, he fought tooth-and-nail to stop the development before the deadline.(16) He formed a plan: The city would buy back the land from the Gellerts, and extend the Twin Peaks park down the eastern slope. The money would come from a bond, which would go to the people of San Francisco for a vote.

But before the proposal could reach the ballot, it first had to pass through Parks & Rec, who balked at the Gellerts’ $6 million price tag (…not to mention the annual $450k in lost tax income and $180k in bond interest payments). They rejected the plan unanimously.(17) Parks & Rec announced their decision during a hearing in September, where Carl Gellert commented, “Some day, these people will thank me” over a “chorus of boos” from the audience.(18)

With no legal recourse left, in the last major session of the year, Morrison urged the Board to join in a symbolic “No” for the pro forma vote, in hopes that Standard would decline to pursue the development in the face of political pressure.

・ ・ ・ ・ ・

I arrive at City Hall rain-soggy and caffeinated. After shuffling through security, and trying not to ruin a couple’s wedding photo while climbing the grand staircase, I open the door to the Clerk of the Board’s office, up on the second floor.

The attendant shows me to an open desk and hands me an oversize brown folder marked 428-62. There are no recordings or transcripts of the Board’s December 17th session. Aside from a handful of notes in the Board’s Journal of Proceedings, this folder is the end of the line.

Most of the two dozen documents inside are the dull-but-critical minutia of legislation, in a hodgepodge of media and style: photostat receipts for lien payments, interdepartmental communiques mimeographed on cheap onionskin, insurance bonds from United Pacific with ornamental illustrations and attached notary forms.

But the rest of it is something else entirely. A trail of breadcrumbs left by Morrison and the opposition, collected and archived back when you could still smoke cigarettes in City Hall and the internet was science fiction. Newspaper clippings pasted onto sheets of yellow paper, fragile with age. A single handwritten postcard from Mrs. William E. Rand in messy cursive.(19)

Towards the bottom of the stack, there’s a letter from the Catholic Interracial Council (on official stationary, signed by hand, and date-stamped in fading blue ink).(20) The Board of Supervisors kept this document, thinking that one day someone might be interested in reading it:

“At this time [mid-1961], Carl Gellert stated in a telephone conversation with the Executive Director of the Council for Civic Unity: ‘I have never sold a house to a Negro…I don’t think there will be any change in this policy.’ “…[The Council] feels a permit to Standard Building Company to build more racially segregated housing is not in the best interests of the city, and violates the most elementary standards of social desirability and social justice.”(21)

Supervisor Ertola moved to adopt the resolution. He filed a brief, to-the-point statement (typewritten on vellum, with a penned correction):

“I believe the Board has no alternative but to approve the map because if we do not it will mean that the [Clerk] will be forced to sign the map and the construction work can proceed.

“The subdivision will put additional property on the tax roll and, in my opinion, the area in question would not be adequate for park purposes.

“Inasmuch as the subdivision plans were approved by [the other departments], I believe it would be inequitable for the Board to take any action but to adopt the legislation before us today.”

In the end, even Morrison’s plan for a symbolic unanimous “No” vote was a pipe dream. The resolution passed 8-3. Immediately after, Supervisor John Jay Ferdon introduced legislation to grant the Board greater control over the subdivision approval process.

・ ・ ・ ・ ・

Today, some 4,000 of us live here on the eastern slope of Twin Peaks, most in the tidy, stacked, slightly nondescript apartments of Vista Francisco.

Historiographically, we remain a grey area. We’re on the east side of the mountain, so we don’t show up in material about the Outside Lands. We don’t have an upscale nineteenth century pedigree, so we don’t show up in material about Victorian architecture or high society. We weren’t involved in anything which formed unique sociocultural enclaves, like the metalworks of Irish Hill, or the strip clubs and beat cafes of North Beach. We were just a grassy hill with some cows on it.

When I asked about this early ’60s development at the library’s San Francisco History Center, they sent me downstairs to the present-day Government desk… where a librarian told me they don’t always have records going back that far.(22) Even though Morrison and the urban environmentalists railed against this development, when compared with their epic (and victorious) campaigns against the proposed freeway through Golden Gate Park, the US Steel Building, or taking down the Embarcadero freeway, Vista Francisco is, at best, a footnote.

The most consistent item which finds its way into our narrative is a shimmering neoclassical fever dream: The Athenæum. The crown jewel of Daniel Burnham’s unrealized 1905 plan—which redrew the San Francisco in the “City Beautiful” style—The Athenæum was to be a Parthenon-like complex nestled between the Peaks, with polo fields and pools laid into white marble. An enormous statue of a woman raising a torch looked out to the Pacific, welcoming immigrants from across the endless sea.(23)

Burnham's vision for San Francisco's Athenaeum, looking west toward Lake Merced from today's Marview Drive. A waterfall pours down from a lake just below the Athenaeum into the valley. The 300-foot-tall female statue, "San Francisco", 1905

Original image from "Report on a Plan For San Francisco," Daniel Burnham, 1905. Digital image from David Rumsey Map Collection.

It’s a beautiful vision…and perfect for the late 2010s: Instagrammable, easy to slot into a fun SF listicle, and perfect to narrate while backed by meandering ambient celeste in the dreamy, even-keel style of an urban design podcast. Escapist, but with just enough reality to hit home, emotionally.

But honestly—and as a lifelong California Leftie and a fan of cheap ’80s underdog movies, it feels slightly weird to write this—in the end, I think it’s better that we ended up with 700 boring units of RM-1 instead of 21 acres of lush, rolling hills or a marble parthenon. But it didn’t have to go down the way it did.

Jack Morrison went on to co-found the organization San Francisco Tomorrow in 1970, which takes its name from a question they pose to the city’s residents: “Will you want to live in San Francisco tomorrow?” In 2018, this question seems almost decadent. These days, many of us seem to be wondering “Will you be able to afford San Francisco tomorrow?” The restrictive development ethos that kept San Francisco looking like a postcard also helped to slow the housing supply to a trickle.

But hindsight is 20/20, and when Morrison fought Standard, San Francisco was still decades away from the asymptotal economics of the tech boom. 1962 was a lifetime ago.(24) In reality, city politics is a delicate, complicated bloodsport—and I’m just another armchair historian, the latest in an unbroken thread of post-internet wannabe Herb Caens, vacillating between heavy footnotes and the boozy syntactical curves of a bon vivant.

It’s one thing to climb up Twin Peaks and see San Francisco from the clouds, and it's quite another to see it from behind a desk at City Hall, pulling in a million different directions at once.

Notes

1. The layout I'm using here is also used by the San Francisco Planning Dept. for notification purposes — and it aligns generally with the view held by most people I talked with. It's worth noting that "Twin Peaks" doesn’t actually exist everywhere. In 2006, the Mayor's office established its own neighborhood boundaries, which splits the area into Upper Market to the east, Midtown Terrace to the west, and Clarendon Heights to the north. The Planning Department lumped it together (seemingly as an afterthought) with the West of Twin Peaks neighborhoods for a comprehensive neighborhood-level overview document it created in 1997. The Supervisorial District boundary snakes right through the mountain: Midtown Terrace is in 7, Twin Peaks are in 8, and Clarendon Heights is split down the middle between the two districts. All of this is very arguable, don’t @ me bro.

2. 2016 ACS: Midtown Terrace Block Groups 1 & 2, ages 0-19: 38.9%, San Francisco average: 15.2%. I didn't include Group 3 here, because it’s kind of an outlier situation: it contains a loop of the Midtown Terrace development, permanent care facilities from the Hospital, and a Juvenile Hall and probation center. While waiting for the 44 bus here, I sometimes see teenagers in button-down shirts with binders, having serious conversations with adults. Further comment is a little beyond the scope of this article.

3. Heather on the Hills. IMDB says most of the Heather was actually Sumac spray-painted purple. lol

4. Due to the success of this model, they renamed the company “Sunstream Homes” some years later. If you live in the Sunset, check your garage! You’re looking for a red metal sign that looks like a license plate. Standard would emboss these with the number of the house in the development. Other builders left similar calling-card tchotchkes.

5. See footnote #6 on this Outside Lands article about the Gellerts for a primary source. It should be noted that racial covenants were sadly common at this time. The website “Mapping Inequality: Redlining In New Deal America” includes more information and an interactive map of the HOLC partitions for San Francisco if you would like to go further into this topic.

6. “Real Estate Sit-In at SF Tract,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 29, 1961. “Basic Brown,” Willie Brown, Simon & Schuster, 2008.

7. This tract is variously reported as 21, 21.5, and 22 acres. I’ll be using the low value for consistency.

8. “Campaign Funds Offer In Zoning Fight,” San Francisco News-Call Bulletin, October 22, 1959.

9. Going through the independent third-party group “The Volunteers for Better Government,” who worked with the reporters to blow the whistle.

10. The News-Call Bulletin summed it up in two cutting paragraphs: “In each of these segments, months, even years, of discussion and dispute with the planning staff, public hearings with the planning commission and public hearings with the Supervisors' committee on planning had transpired. And through these long periods, the final official decisions had run counter to the Standard Building Co. Wishes.

In each, the supervisors on Monday reversed field, and endorsed the Standard Building Co. proposals, with Supervisor Joseph Casey carrying the ball on the favorable argument, from a special statement a Standard official had prepared, while another Standard representative consulted supervisors in their back room.” October 22, 1959.

11. "Money Offered in Zoning Case," San Francisco News-Call Bulletin, October 22, 1959.

12. The original plan with around 900 units was negotiated down to around 750 (“Twin Peaks Plan Revised,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 10, 1962). There were additional negotiations for the second half of the subdivision, but it’s outside the timeline of this article (See Chronicle, Sep. 8, 1967). Side note: The zoning designations used in 1962 have since been superseded. Vista Francisco’s modern zoning designation is RM-1, which refers to Residential Mixed-Use, with the number (1–4) relating to density (as measured in square footage per unit). See the Planning Department's enormous Zoning Map.

13. Once a subdivision had been approved by the City Engineer and Public Works Department, the Board of Supervisors technically had no legal power to reject it.

14. See this 1985 retrospective (or the original typed version!) written by Morrison for the early history of, and some of his major works with SFT.

15. “Probe Asked In Election Fund Offer,” San Francisco News-Call Bulletin, October 22, 1959. “Twin Peaks, Grass or Apartments?” San Francisco Chronicle, September 13, 1962.

16. This was before the change to district-elected supervisors (referred to now as an at-large supervisor).

17. “Gellert Fights ‘Blight’ Tag Hung on His Apartments,” San Francisco Chronicle, August 24, 1962. Note: $6m in 1962 is about $49.25m in 2018.

18. “Twin Peaks Falls To Builder Gellert”, San Francisco Chronicle, September 14, 1962.

19. “Dear Sirs: Please give San Francisco a real Christmas present, and save what is left of Twin Peaks from the Gellert Bros. subdivision. Have the courage to vote like sv. Boas.” (Boas had stated he would vote against the development.)

20. “Jan 18 9 55 AM 62”

21. Letter from Dr. James Carey, President of the Catholic Interracial Council of the San Francisco Bay Area, written January 17, 1962. Addressed to the President of the Board of Supervisors, cc: Mayor Cristopher, Director of Public Works, and City Planning Commission.

22. They did have what I was looking for, though! Shoutout to the SFPL Gov’t desk.

23. In 1934, Arts and Crafts architect Bernard Maybeck added a giant waterfall feature, spilling down from the top of the complex into a basin (somewhere in present-day Midtown Terrace). A nighttime rendering shows the cascade sparkling in the glow of electric street lamps.

24. Carl Gellert passed away in 1974. He leaves behind a philanthropic organization which continues to operate today in the greater Bay Area. Last year, they granted $2.6m to a wide variety of recipients: hospitals and clinics, tuition assistance (mostly private Christian schools), homeless shelters and more. Fred Gellert passed in 1988. Jack Morrison passed in 1991.