Rancho San Miguel Disappears

Historical Essay

by Mae Silver, from the chapbook, Rancho San Miguel

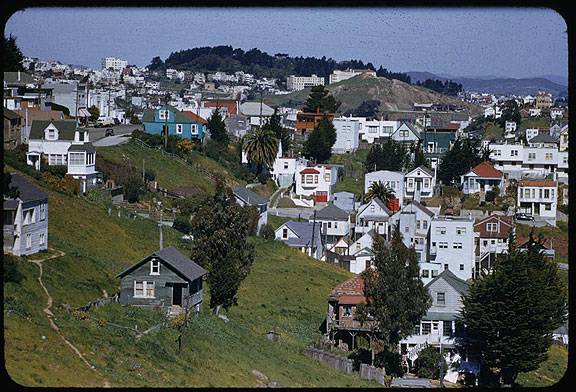

It wasn't until San Francisco was "built out" in the post WWII era that the higher, hillier parts of town lost forever their rustic, semi-rural quality. Here is a small cluster of workers' housing near today's 24th and Burnham, c. 1930s.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

March 15, 1955, view north from top of Farnum Street in Diamond Heights across upper Noe and Eureka Valleys towards Corona Heights.

Charles Cushman Collection: Indiana University Archives (P07707)

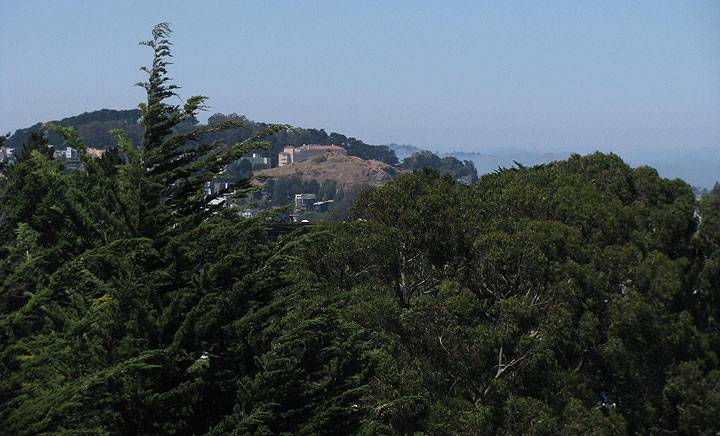

July 26, 2009, same view, taken from top of Farnum Street in Diamond Heights, looking north towards Corona Heights.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Farnum Street dead-ends into Haas Playground and Park at right between the two large trees. The photo above was taken at the left (north) edge of the park, directly opposite Farnum Street, to duplicate the Cushman photo further above.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

José de Jesús Noé, like the other rancheros in San Francisco, had no reasonable means to preserve his rancho. A dynamic force had captured San Francisco. The frenzy for gold, the instant-riches mindset had invaded the gracious, self-contained lifestyle of the ranchos. There was no way to return to those pastoral days. The value of land in town became linked to the ebb and flow of treasure seekers needing land to live on as they commuted to the gold fields. Wages to police the ranchos were high. Costs to litigate rancho claims against the U.S. government mounted. A series of droughts and floods whittled profits of the ranchos. The Financial Panic of 1857 also hurt San Francisco. Noé must have weighed all these factors and decided to sell.

On March 14, 1862, already sick and sensing he was near death, José de Jesús Noé wrote and signed his will. The Bulletin published it on June 16, 1862:

"In the name of Gold Almighty amen: Being sick and having complied with my spiritual obligations, desirous of setting my temporal affairs--I, José de Jesús Noé, being of sound mind, do herewith declare that these presents are my last will and testament by which I dispose as follows:

i. I declare I have no passive debts.

2. I wish that four masses of one dollar each be said to the Virgin of La Soledad de Santa Cruz with the corresponding candles.

3. Also that four more masses be said to the Virgin Dolores. These masses to be held at the Mission of Dolores.

4. Gives to his actual wife, Donna Catarina Valencia, the adobe house and the "Solar" on which it stands, near Centre Street (16th St.) at the Mission (San Francisco), and the frame building and lands near by.

5. Gives to his daughter and minor sons, Jeses (Jesús) and Vicente, another wooden house and land on Centre Street, with 29 feet frontage.

6. Disposes of his ranch of San Miguel, to the south of the mission, containing 200 varas square to each of the latter, and twice that to the former--the balance of the ranch to be divided equally between his daughter Dolores and two sons, Jesús and Miguel.

7. Divides the Rancho de las Arbas, in San Mateo County, equally among his wife and children.

8. Bequeaths all the remainder of his stock and property to his daughter, Dolores and sons, Jesús and Vicente, equally.

Other clauses refer to administration etc., and 12.) recommends to his sons, that if, for some cause or other, differences should arise between them, they should avoid all legal proceedings, and submit such questions to the decision of friendly arbitration."

Noé had not sold all of Rancho San Miguel. He willed some of this property, buildings, and livestock to his family. Most revealing about Noé's temperament was his recommendation that his sons should avoid all legal proceedings if they have familial differences and instead engage in friendly arbitration to resolve them. This advice clearly echoed the wisdom of the Rancho Period.