Unsettled: Warriors in the Cove of Weepers

Historical Essay

by Adriana Camarena

Originally published in El Tecolote February 8, 2018

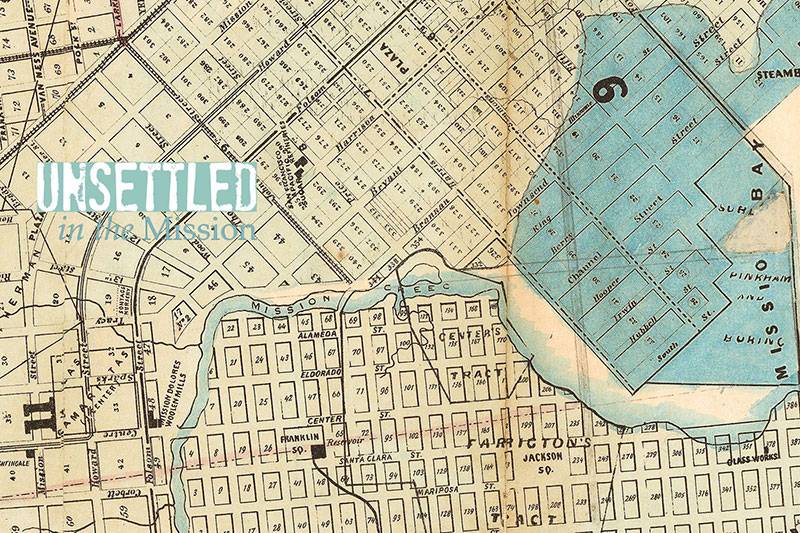

Detail of 1864 James Butler, Map of City and County of San Francisco, The Pacific Mining Journal, showing the Las Camaritas contested land tract and Mission Creeks.

Map: courtesy David Rumsey map collection

The Ohlone—the original peoples of this bay—were known to ritually and demonstratively grieve sorrows. When suffering a great sadness, they would singe their hair short and smear handfuls of ashes, earth and ground stone on their heads, faces and bodies. Women were known to draw blood from their cheeks and breasts when a loved one died. Their tears would have cut streaks across their smudged and bleeding faces, while they openly cried.

On Aug. 5, 1775, Spaniards entered San Francisco Bay on the packet-boat San Carlos, and anchored off of Angel Island. Expeditions were immediately launched to explore and map the area. A few weeks into their exploration, Second Pilot Juan Bautista Aguirre took a few men out on a longboat to sound the southeast arm of the bay. Upon an inlet of the bay, the mariner observed three natives weeping. Impressed, Aguirre named this inlet La Ensenada de los Llorones or the Cove of Weepers, after the mourners.

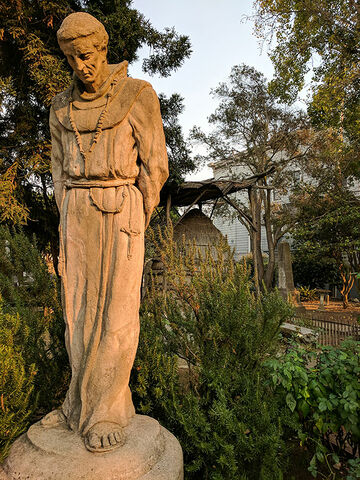

A statute of Saint Francis of Asis with replica of an Ohlone tule house in the background at the cemetery of Mission Dolores, Oct. 2017.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

A year later, in June 1776, the Mission of San Francisco de Asis was founded on the banks of a large tidal estuary called the Lagoon of Sorrows. Father Palou described it as being “in line of sight to the Cove of Weepers.” The Lagoon had been named after the Creek of Sorrows that flowed into it from the hills above. Like the waterways, the mission came to be known as the Mission of Sorrows, Misión Dolores.

A trail of tears was effectively wrought upon the native populations of the bay by the missionaries. The missions of California were economic units of production that required slave labor from Indian converts. During the next 30 years, the Yelamu-Ohlone people of the nearby town of Chutchui would be wiped out, and a wide dragnet of “recruiting” backed by the muskets of the Presidio soldiers would round up original peoples from the East, North and South Bay to satisfy the productivity of the Mission Dolores. Notoriously high death rates at the missions, compounded by a measles epidemic in 1806; incessant forceful recruitment; brutalization and persecution of runaways; and diminishing choices for survival outside the economy of Mission Dolores would eventually lead to Ohlone survivors into succumbing to the mission’s seemingly inescapable dominance.

Warriors in the Cove of Weepers

A few months back, on a hot sunny day of September, I walked the length of 16th Street from the Mission Dolores to reach the inner bay. Past the aging black SRO residents sitting on the BART plazas at Mission Street, past the old industrial corridors of the northern Mission boundaries, up the foothill of Potrero, past the ghost of the old Seals Stadium that once stood between Bryant and Potrero streets, and downhill into the massive new medical complex and multimillion-dollar condos of Mission Bay, I came upon the landfilled edge of the water. Until recently, native flora and fauna were making a comeback here. Now the skies were darkened by an invasive species of bird: blue, red, white and yellow motorized cranes that swirled incessantly overhead, readying the return of the Golden State Warriors to the Cove of Weepers.

The Cove of Weepers was renamed “Mission Bay” in the onslaught of the 1849 Gold Rush by the speculators who partitioned and sold it off in “water lots.” It was voraciously landfilled in the following years. All that is left of the Mission Bay is a channel that seemingly pops up out nowhere, next to the houseboats, under the 3rd Street bridge, past the side of the Giants’ ballpark, and out to the open bay. It still carries the waters of the old Creek of Sorrows.

On Jan. 17, 2017, the Warriors broke ground for their new arena in the Mission Bay neighborhood. The new stadium will be located a straight shot down from the Mission District on 16th Street, where the street meets the bay. The Warriors’ new stadium is a coup of real estate speculators who in a decade have turned Mission Bay into a millionaire’s playground, where the extremely rich will come to stay, pay and play. Some Warriors’ players will be among the new rich residents.

Poor People’s Cove and BARTer Plaza at 16th and Mission

“Upstream” from the Warriors’ new stadium is an extremely impoverished community in the Mission. On the northeast corner of the 16th Street BART station, Black neighbors gather daily to dance and sing around a boom box. Across the street at the southwest BART plaza, regulars like “Birdman” and a community of unhoused folks rest their weary bodies against the back walls. Coming and going, the pushcart homeless rattle through, stopping to warm their bones under the fickle San Francisco sky and drink beer. Homies sometimes still hang out.

Rush hour sunset and foot traffic at 16th and Mission streets (Feb. 5, 2018).

Photo: Adriana Camarena

The BART plazas are a daily market where the extremely impoverished of San Francisco cover their most basic necessities by bartering thrift-shop quality items. Once upon the plaza, but now pushed by police to the west side of Mission Street near 15th, Black Cuban-Americans also lay out their ware for sale or barter in a market colloquially known as La Pulgüita, “the little flea market.” The BART plazas are not merely transport hubs, but networks of survival based on peer-to-peer poor people exchanges. Here a diverse population coexists via tenderly stitched relationships of trust, finding a way to survive the burdens that got them there in the first place.

Hotel City Hub at 16th and Mission

The BART plazas at 16th and Mission streets are also the origin, the focal point, of a highly concentrated circle of single room occupancy (SRO) hotels or ‘residential hotels’ in the Mission. Many of the regulars at the plazas live in SROs. After the Gold Rush, San Francisco became known as “Hotel City” for its berth of lodgings available to the itinerant or permanent low-income resident, including immigrants. In 1930, there were approximately 90,000 residential hotels or “rooming houses,” which by 1990 were reduced to 20,000. As the city gentrified through the DotCom era, residential hotels were demolished and turned into condos. The 2016 San Francisco Housing Inventory of the Planning Department shows that that there are only 498 residential hotels left in the city today.

Protesters demonstrate at 16th and Mission streets (Jan. 25, 2018) as part of the “Save Mission Street!” campaign.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

According to an informal 2015 survey by the Mission SRO Collaborative, within a half-mile radius of 16th Street and Mission street, are 34 of the approximately 50 SRO hotels in the district. The majority of the Mission’s SRO residents are middle-aged and senior residents, who survive off of disability assistance, and cover their health needs through Healthy San Francisco (the city’s single-payer health program) or MediCal.

The neighborhood hangs on to its last stock of rental rooms for a population battered by the lack of housing options. The city has announced plans to increase affordable housing. I talk about this with my friend Dell, who I met back in 2013 at the corner of 16th and Mission. Dell is an African-American man, originally from Chicago, who has lived in SRO hotels in the Mission nearly continuously for 15 years. “The problem with the city saying it’s ‘affordable housing’ is that their definition is for someone who makes $80,000 to $100,000!” he explained, exasperated. “Half the people down here make way below $20,000 a year. They need to be making ‘impoverished housing’ down here!” According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, in 2017, a six-figure salary of $105,350 for a family of four was considered “low income” for San Francisco. This masks the fact that the city’s poor and working-class communities are facing impossible choices for surviving the escalating class warfare and accompanying gentrification brought on by the Tech Rush.

SROs are also hard places to live in because of the isolation they impose on residents. “If you had a house you could have friends come over for dinner. In a hotel, visitors need to be on a list by 9 p.m.,” said Dell. “I can’t go out to a club, meet a woman, and bring her back, either. Besides, there is the stigma of living in an SRO. Once I was asked by a date if this was a halfway house or I had just gotten out of jail. What type of place is this to bring someone to hang out in, anyways? When you enter, it feels like you are going into a state institution based on the number of cameras watching us up and down the hall. The elevator is a death trap. I’m living in a room the size of a work cubicle. The only way to get air in is to open the door. I take a chance at a rat running into my room. I’m also near the bathroom. If anyone takes a crap, I’m going to smell it every time. You end up just making friends with people at your same level of society … For seniors, the isolation is even harder.”

Dell and his friends take care of each other to muster through. “One thing that is lovely about 16th is that unless you are dangerous, we not only will accept you, we will try to help you!” At times Dell has become very disillusioned about life. “I’ve thought of offing myself from time to time, but then I think about Vanessa and all my [other] friends on the corner. They would be angry that I stopped trying, that I left them like that. And, who would take care of them, if not me?” His love for his friends keeps Dell going.

The first time I met Dell and took down his phone number, he told me to identify him in my address book as “SRO Survivor.”

SRO Survivor

I ring up Dell to consult him again about how someone survives in an SRO. This time we meet at the McDonald’s over by 24th street for a cup of coffee. We go there because over by 16th Street, the McDonald’s closed about two years ago and the Burger King just last month. The day the Burger King shut down without notice—the go-to joint for seniors and SRO residents relying on Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) cards for food—the little old men and women who gathered there daily didn’t know what to do with themselves, and sat despondent on the remaining BART benches with Dell’s friends.

Dell, a longtime Mission SRO hotel resident. (Feb. 1, 2018).

Photo: Adriana Camarena

Dell breaks down SRO economics further for me. “If you’re on GA [General Assistance] your monthly allowance is about $935. Now, your monthly SRO rent is $600. GA directly takes that out of your paycheck. After rent, you’re left with $280 in food stamps and $55 in cash for the month, but you work cleaning up the streets for this money. Check it out, you’re working for that money, but since they call it ‘General Assistance,’ they don’t call it a ‘job.’ You get no vacations, and you’re qualified for nothing else. If you stop working, you are cut off, and you have to start all over again to get into the system. It is legalized slavery!”

Dell continues, “With what you have left, you have to cover your other costs of living. In this city, you can easily spend $100 just on daily living expenses: You need to pay a cellphone. You need to buy a meal three times a day. Nevermind a meal, just a sandwich is a minimum of $10 nowadays, or a $7 meal at the McDonald’s. That’s going to be $30 on a conservative budget. Add the bus: at least $2.75 and more if you need to make several trips. If you have a habit, there’s that too. Add your laundry and whatever else comes up in a day. …” Dell nods seriously, “A lot of people are going to sell those food stamps to the little old Chinese ladies for some extra cash.”

There is an alternative to taking General Assistance from the city Dell explains. “Without a chance at employment or training, many people would rather take federal money—SSI—since they can keep more of it for living expenses, about $370. … Many of the disabled homeless people here are homeless by choice, because they’d rather keep their SSI money than pay a hotel. … Now, those buildings down the ways? They’re for techies making at least $125,000 a year, paying $6,000 dollar to $3,000 dollar a month rent—rent!”

Monster in the Mission on Public Space

A few years ago, the northeast corner of 16th and Mission became a target for demolition by Maximus Real Estate Partners to build two 10-story luxury condo towers over the BART plaza. Of the 331 units proposed, only 41 would be “affordable” housing. Housing rights organizations in the city, Latino associations, Mission residents and a multitude of others coalesced into the Plaza 16 Coalition to push back against the development that is, by now, best known as the “Monster in the Mission.” Maximus has plastered the Mission BART stations with ads that proclaim “I am not a monster,” and feature images of working-class resident. Recently, a teacher depicted in the posters came forth to say that the campaign was miscommunicated to her as a project for affordable housing. She would never have agreed for her image to be used had she not been duped.

June Jordan School student protesters with the “Save Mission Street!” campaign at 16th and Mission Streets (January 25, 2018).

Photo: Adriana Camarena

The ugly truth is that in whichever way Maximus spins this tale, it is a story of a speculator that came gunning for Wild West profits on the block. They saw an opportunity to landfill 16th Street and Mission with condos for the rich, now that the Mission Bay for millionaires is a three point shot away.

Speculating on Sacred Indian Burial Grounds

John Center arrived in 1849 during the gold digger invasion, but instead of heading towards the hills for metal, he squatted land on the banks of the Lagoon of Sorrows, which once belonged to Mission Dolores. This tract of land was known as “Las Camaritas,” and lay roughly from 16th to 15th between Mission and Folsom streets. Following the decline of the mission system in 1834, José de Jesús Noé, a Mexican Californio, was granted the land in 1840. Las Camaritas had a spring, a small seasonal lagoon and a willows grove. The landing on the Lagoon of Sorrows was also near this tract, built by land thieving missionary fathers in earlier times. From there, a quick paddle down on the lagoon towards the Old Mission Creek would see a boat out to the bay.

In a long and convoluted story of squatter wars over Las Camaritas following the Gold Rush, suffice to say that John Center finally obtained quiet title in the 1870s. At the 1909 inauguration of the new Mission Grammar School and Marshall Elementary School, on the northeast block of 16th and Mission, the then mayor “told of its existence as an Indian burial ground and later as the orchard of the late John Center, the pioneer who deeded the school property to the city.” The term “Indian burial ground” was back then code for shellmound.

Shellmounds were built by the Ohlone near the ocean or the banks of waterways such as rivers, creeks and wetlands. They are hills made from refuse of shellfish, such as mussels, clams, cockleshells and oyster shells, but also of mammals, birds, fish and reptiles, interspersed with ash from cooking and big time feasting. Shellmounds also had other uses, such as providing elevation over flatlands to assist hunting. Ohlone ritually buried their dead in shellmounds, built in an earlier time. With shellmounds, the Ohlone seem to make a statement of undeniable belonging to that land: We built this. My ancestors are of here. I am of here.

Upon Ohlone bones, on the banks of the Lagoon of Sorrows, Center built an orchard that fed the 49er hordes and made him very rich. He died in 1908 being remembered as the “Father of the Mission” for his involvement in the land rush development of the neighborhood.

It would be a deep tragedy if Maximus succeeds in building its condos. History would repeat itself again as an entire existing community, with its own distinctive culture, is destroyed to make way for a speculator who will once again desecrate Ohlone sacred grounds.

Multi-Nation Cross-Roads at 16th and Mission

A port city promises unknown encounters with those who are different from us, and 16th and Mission streets, as it is now, delivers on that promise.

Hwa Lei Market—next to where the Burger King used to be—is a tiny place, forcing clients to rub shoulders and exchange pleasantries when squeezing down the aisles. It is the go-to place for many seeking Asian and Southeast Asian specialty items to prepare dinner like grandma used to make. The Hwa Lei Market is a reminder that the Mission is home to a multi-ethnic enclave of various Pacific cultures, and has been since the 1960s. Next to Hwa Lei is a greasy spoon Chinese restaurant favored by low-income patrons of every race. A bit further down is the City Club Bar, one of the last local Latino day laborer watering holes in the entire Mission. All these cultural niches will be razed by the Monster in the Mission.

Across from the City Club Bar, Capp Street begins its trek across the Mission. On any given day on those first blocks moving south, there are homeless people traveling to the Mission Neighborhood Resource Center that provides critical survival services. Across is the Native American Health Center that welcomes peoples of all tribes for specialized services, and up on Julian Street near 15th is the Friendship House Association of American Indians that provides rehabilitation services, and even a sweatlodge for ceremonial healing.

The Mayan immigrant road to the American Dream in San Francisco also has its depot at 16th and Mission. People from Peto, Mamá, Oxkutzcab, Maní, Akíl, Teabo and more towns hail each other as they move from their homes to work and back, or head off for authentic Yucatecan grub just up the block on Mission Street. Asociación Mayab, serving the cultural interests of Mexican and Guatemalan Mayans, is in a building on the northwest side of 16th and Mission streets.

From the Mission SRO Collaborative’s 2015 survey we also know that SRO populations retain the diversity for which the Mission was once known: African-American, Afro-Caribbeans, Latino, Asian, Native Americans, Pacific-Islanders and White poor residents all living together.

Three-point Game

In 2019, the Warriors, world renowned for their game-changing three-point dominated style of basketball, will move back to San Francisco to take up residence in the old Cove of Weepers. The Warriors were founded as the Philadelphia Warriors in 1946. Their first logo depicted a cartoonish Indian dribbling a basketball, drawn in a style reminiscent of Sambo representations of African-Americans. Relocating to the Bay Area in 1962, they became the San Francisco Warriors, and their logo was changed to an Indian headdress known as a war bonnet. In 1968 the National Congress of American Indians started a campaign to end the use of derogatory and harmful stereotypes of Native Americans such as the ones the Warriors had used for so long. The NCAI has since insisted pro-actively that stereotypes about Native-Americans encourage a legacy of violence towards them, and that seeing themselves depicted as subhuman mascots for other’s entertainment damages their self-image.

Marvin Zita, a security guard and Mission resident, plays basketball on Feb. 6 at Jose Coronado Basketball Courts at 21st and Folsom streets.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

From November 1969 to June 1971, the movement of Indians of All Tribes, born from their gathering near 16th and Mission, captivated the world by occupying Alcatraz. For a short period, they recovered ancestral lands, even if symbolically. That same year, 1971, the Warriors moved to Oakland, changing their name to the Golden State Warriors, quietly dropping cultural appropriation from their logo in favor of the city and bridge references. It is unclear whether the owner was responding to the rise of the Native American movement at the time, or just business as usual. In any case, once before the team has already divested itself from a racist past.

Bay Area land speculation history teaches that real estate and racist oppression go hand in hand. The Warriors franchise will soon be surfing into the Cove of Weepers on a King Tide of rising class and racial inequality in the city. The team owners and players have a chance to stand against the horrid long legacy of new settlers in the Cove of Weepers and instead stand for social justice with the poor and disenfranchised of this city, and their diverse communities.

A fight against real estate speculators in working class neighborhoods is its own three point effort: 1) Protect the residential havens that low-income workers and the poor have created for themselves, 2) Expand public spaces where we can engage in unmonetized and horizontal relationships, like the SRO barterers at 16th and Mission, and 3) Support the Ohlone bay tribes’ work to return to their sacred lands. But for the ongoing flagrant fouls of police abuse, we get an “and-one”: 4) End police impunity.

The James Rolph Jr. Basketball Courts at Potrero and 25th Streets, at the south of the Mission, are open to the public. Here on any given day, indigenous day laborers from Chiapas gather for a pick-up basketball game. They play a fast game, taunting each other in their native tongue. I find myself, on the outside looking in, feeling fortunate, still able to witness baller trash-talk in Tzeltal, courtside in a Mission public park, in 2018.

About Unsettled

Unsettled in the Mission is a series of literary non-fiction essays by Adriana Camarena to be published periodically as supplements in El Tecolote through January 2019. Her writing is based on portraits of the traditional working class and poor residents of the Mission District for an exploration of Latino identities and histories. This is a collaborative project supported by the Creative Work Fund, however, the views and opinions expressed in “Unsettled” are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Acción Latina.

About the Author

Adriana Camarena is a Mexican from Mexico, complicated by an upbringing in the U.S., Uruguay, and Mexico. She became a resident of the Mission District of San Francisco in 2008. Since arriving in the Mission, Adriana began collecting tales of borders, line-crossings, and overlapping identities told by residents to provide a layered picture of this traditionally working class immigrant neighborhood in California. To learn more about the author and her work, please visit her website.