AFFORDABLE HOUSING IN THE TENDERLOIN

Historical Essay

by Rob Waters and Wade Hudson, excerpted from "The Tenderloin: What Makes a Neighborhood" in Reclaiming San Francisco: History Politics and Culture, City Lights Books 1998)

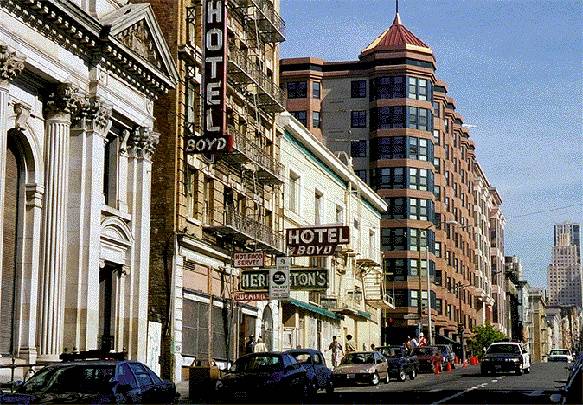

Jones between Golden Gate and McAllister, 1997.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

| The Tenderloin as been a hub of activism since the 1950s and the need for affordable housing along with appropriate dispersing of resources for its residents has continued to be a main issue. With problems that every other major American city faces: jobs, housing, extreme poverty, the Tenderloin sees these problems personified in the faces of immigrants and locals alike trying to take advantage of limited state and government assistance through a number of charities and non profit organizations that have the will but lack the funds to achieve the way out of the constant cycle. |

Perhaps no corner in the Tenderloin better symbolizes what has--and has not--changed in this neighborhood over the past twenty years than Jones and Golden Gate. One side seems almost like a time capsule, the site of a an endlessly repeating ritual that's been acted out each day since St. Anthony's served its first meal in 1950. These days, the dining room's staff and volunteers are serving more meals than ever, nearly 2,000 hot lunches to some 1,200 people, most of them homeless or with incomes so low they can't afford their own food. They are people like Eugea Shaw, a 47-year-old African American who's lived or worked in the Tenderloin for nineteen years. Or "Granny Gear," as she gives her name, an unemployed former secretary and bartender who ate her first meal at St. Anthony's in 1970. Gear, 50 and nearly toothless, survives today on the $340 a month she gets from the city's General Assistance program and lives in a small hotel room. Lately, she says, she's been eating at St. Anthony's every day. "I don't have a refrigerator," she explains, "so it's hard for me to make my food stamps last."

Across the street, the building at 111 Jones, built and run by an arm of the Catholic Church known as Mercy Services, is also a sanctuary for the poor, but the feeling could not be more different. The tasteful construction and quiet ambiance creates a sense of peace and serenity for the 108 families lucky enough to live there. "When you come inside this building," says resident Kira Slobodnik, "you forget about everything outside." Slobodnik, 62, and her husband fled the growing anti-Semitism of her native Ukraine and came to San Francisco in 1992. A university graduate and former Russian teacher in Kiev, Slobodnik shares her home with other immigrants and refugees from Russia, China, or Vietnam, along with a few native-born Americans like long-time Tenderloin resident Joe Kaufman, a burly activist and poet who's been involved in community organizing campaigns since he moved to the Tenderloin in the late 1970s. More than 3,500 people applied to move into the building's 108 units before it opened in 1993. When a lottery was held to choose among the applicants, the Slobodniks and Kaufman hit their number. Eugea Upshaw, the regular diner and former employee of St. Anthony's Dining Room, did not.

The shifting fortunes of Kira Slobodnik, Joe Kaufman and Eugea Upshaw over the past twenty years illustrate the changes that have taken place in the Tenderloin and point up the challenges facing those who grapple with the seemingly intractable problems of poverty, housing and jobs in America today. Impassioned activists, long-time Tenderloin residents, newly arrived immigrants, and caring providers of social services have spent the last two decades struggling to improve the community and to make it a more livable place. Their work, which reached its peak of potency in the mid-1980s, prevented the neighborhood from being devoured by the forces of development and gentrification and preserved the Tenderloin as a low-income community.

But the limitations of their work are also clear. For every Kira Slobodnik and Joe Kaufman who managed to get a place in the sun in a building like 111 Jones, there are scores of Eugea Upshaws and Granny Gears who wait in soup lines for their meals and spend their nights in cheap welfare hotels or sleep in doorways on the street.

Tenderloin activists succeeded in awakening and mobilizing their community, but no neighborhood can make a revolution within its own borders. The Tenderloin, more than most neighborhoods, is buffeted by developments across the ocean and policy shifts across the country. Even the lucky lottery winners who got into the oasis at 111 Jones Street may find their new residence to be less stable than they might have thought.

One source of racial tension is visible at the corner of Golden Gate and Jones, where Granny Gear and Eugea Upshaw stand in line at St. Anthony's, across from the castle at 111 Jones. In many ways, that building, and the other nonprofit housing in the neighborhood, is a product of the community mobilization of the 1980s. Neighborhood activists put non-profit housing on the agenda as a way to house the Tenderloin's poor, and to ensure that they would continue to be able to live in their neighborhood. Yet few previous residents of the Tenderloin actually live in the 108 units at 111 Jones, and only three African-American families. The same is true of a new building developed by Network Ministries on Ellis Street.

The agencies that developed these buildings point out that because they were using government funds to buy the land and construct the buildings, they could not restrict the applicants to neighborhood residents, nor could they establish quotas to ensure that the racial breakdown of the building reflected that of the neighborhood. Their only option was to run a lottery, open to all who earned enough money to afford to pay the rents--around $375 for a one-bedroom apartment--but not so high as to be above federal definitions of low income. The result is a strange twist on gentrification: People who get General Assistance (locally-provided welfare for single people) can't afford to live there, but people getting higher federal disability benefits can.

These non-profit developers were faced with a decision: They could play by government rules and provide housing mostly for immigrants, most of whom who had not lived in the Tenderloin and had not been part of the neighborhood's struggles, or they could refuse and not build the housing at all. Given these choices, their decision is certainly defensible, but it plays into racial division and perpetuates troublesome notions about the deserving and the undeserving poor.

In the Tenderloin, Southeast Asian families with children are seen as deserving, and a number of agencies are working effectively on their behalf. The Bay Area Women's and Children's Center, for instance, has led the crucial and successful fight to establish a Tenderloin grade school, a campaign that received a great deal of favorable media attention. But efforts to start up a drop-in center for crack-addicted women with children, primarily African-Americans, has met with fierce opposition from other Tenderloin groups fearful that such a program would bring more drug addicts into the neighborhood.

At one time, such disputes would have been hashed out within the neighborhood. The Planning Coalition would have discussed it in a board meeting; the Tenderloin Times would have covered the debate in a story. But today, there is no community-wide forum, no group that can really perform the function of bringing neighborhood groups and people together to discuss ideas and conflicts. Instead, there is an increasing sense of competition and infighting among neighborhood organizations. But beyond the neighborhood's own mistakes and failings, it is suffering from forces that are way beyond its control.