Business Elite Consolidates Its Class Power

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

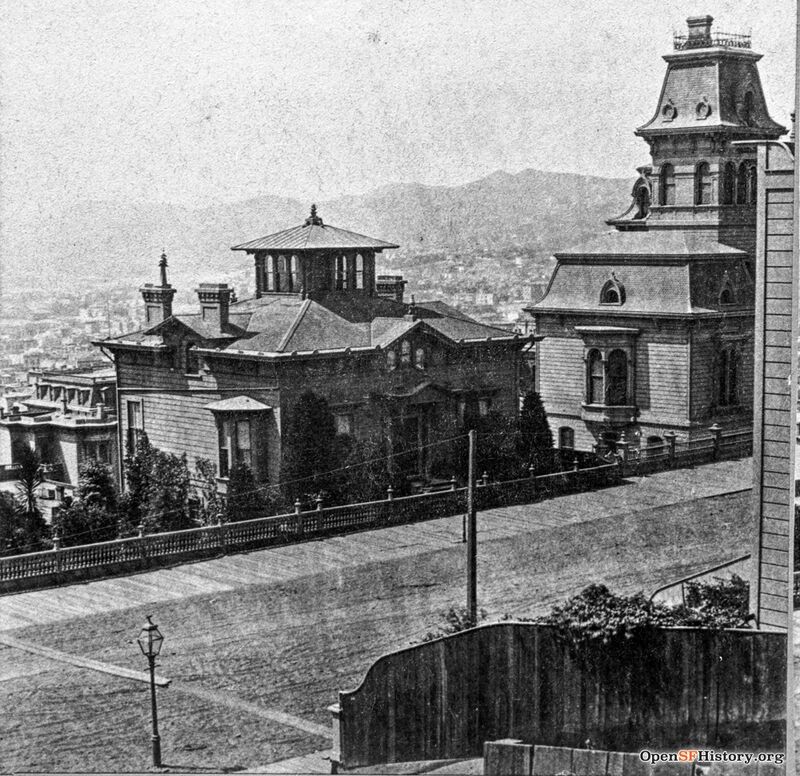

California and Mason c. 1880. Victorian mansions on California between Mason & Taylor. Richard Tobin residence on right. Left house built for Leonidas B. Benchley in 1863. Edward B. Pond, who was mayor during 1887-1891 and was formerly a liquor merchant, purchased house in 1877 or 1878, and replaced with new building in 1889.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org, wnp37.02311

Political office attracted men of lesser wealth than Stanford, Perkins, and Goodall. Henry M. Black, an Irish immigrant to San Francisco by way of Boston, manufactured prize-winning carriages and served on the city school board as well as in the state legislature. Edward Pond, a native New Yorker whose wholesale liquor business allowed him to live comfortably at a respectable California Street address, served as director of the San Francisco Savings Union and the Sun Insurance Company, as well as a city supervisor and mayor.(33)

Other businessmen devoted attention to social organizations and provided both the capital and the loyalty that made them pivotal institutions in the city’s life. Kalman Haas and William Steinhart, German Jewish immigrants, were typical. The grocery business of Haas Brothers was well established by the eighties, and Kalman Haas belonged to the Chamber of Commerce and the Board of Trade and played a leading role in a number of Jewish charities. Steinhart was director of the Pioneer Woolen Mills and the Gold and Stock Telegraphy Company, a charter member and trustee of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum, and the founder and first president of the B’nai B’rith organization (1856).(34)

Steinhart and Haas, like Horace Davis, James Phelan, William Alvord, Peter Donahue, and Charles Crocker, were among the most prominent businessmen in San Francisco from the 1860s to the 1880s. Journalist Henry George may well have had them in mind in 1868 when he wrote that “the great city that is to be will have its Astors, Vanderbilts, Stewards and Spragues, and he who looks a few years ahead may even now read their names as he passes along Montgomery. California, or Front streets.” George proved correct in his guess that men with “established businesses” would “become richer for it and find increased opportunities; those who have only their own labor will become poorer, and find it harder to get ahead.”(35) As Peter Decker has written in a recent study: “Occupational advancements were limited to the white-collar sector.” and movement “from the blue-collar world into either the white-collar occupations or the elite ranks declined significantly after the 1850s.” Decker’s analysis of the “second generation” of the business community (1870–1880) also makes the point that by the 1880s, stockbrokers, bankers, real-estate speculators, company executives, importers, and manufacturers, along with attorneys and physicians, accounted for nearly two-thirds of the total group of economic leaders.(36)

This business elite, well established by the end of the eighties, continued to shape the direction of the city’s economic life during the half-century after 1890. In this respect. San Francisco presents a striking illustration of Thomas Cochran and William Miller’s observation that it is “impossible to exaggerate the role of business in developing great cities in America.”(37) Charles Lindblom’s words apply as much to San Francisco as to eastern and midwestern cities. In San Francisco as elsewhere, “a large category of major decisions” would be “turned over to businessmen, both small and larger.” Business leaders would “become a kind of public official and exercise what, on a broad view of their role, are public functions.” Businessmen played a “privileged role in government.” their influence “unmatched by any leadership group other than government officials themselves.”(38) Herbert Hoover, writing some twenty years after leaving the White House, used similar language when he described his friend Milton H. Esberg as one of San Francisco’s business leaders whose role in urban development “represented a phenomena [sic] unique to American life. The greatest good fortune of American villages, towns, and cities,” wrote the former president, “is a citizen outside its government who gives that leadership which makes for cooperation in the spiritual and physical progress of the city.”(39)

Precise definitions of business leadership elude historians because, as Burton Folsom has written, “no one has yet figured out a foolproof way to measure someone’s economic influence.” One standard that provides useful information is membership on the boards of directors of incorporated companies. If a person who holds at least three directorships in San Francisco firms (two if he was a company officer) is considered an “economic leader,” some two hundred men qualify for the title during the 1890-1930 period.(40) Several dozen of this number, the officers and directors of the city’s largest companies, comprised the nucleus of San Francisco business leadership. At the center of this network of individuals stood James Duval Phelan and William Henry Crocker, both born in 1861. Upon his father’s death in 1888, young Crocker assumed responsibility for the Crocker railroad and banking interests. Phelan took primary control of family real estate and banking interests when his father died in 1892.

The younger Phelan lived until 1930, and “Will” Crocker died in 1937. Their stately funerals at St. Ignatius Church and Grace Cathedral attracted “the wealthy and prominent... in shining limousines” as well as “others who walked.”(41) The honorary pallbearers—some three dozen friends of the deceased—comprised a quarter of the city’s economic leaders, whose participation on boards of directors linked them with most of the rest of San Francisco’s business leadership. Like Phelan and Crocker, these men were responsible for the direction of San Francisco’s largest industries, banks, insurance companies, land development firms, shipping and transport companies, and utility companies. Whether Protestant, Jewish, or Catholic, the men who gathered to pay homage to Crocker and Phelan shared the conviction that profitable business and urban progress went hand in hand. As Leland Cutler, who represented the Chamber of Commerce at the Phelan funeral, put it years later:

I suppose my participation in public affairs attracted business to my company and I was always on the lookout for it. I can’t recall, however, of any civic work I did with the idea of gelling business. I never gave it a thought. I like people, I wanted to help my city and believed in progress generally.(42)

Phelan Building c. 1910.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org, wnp59.00127

Phelan’s work as president of the Federation of Improvement Clubs of San Francisco, like his chairmanship of the Adornment Association (which aimed to create a “city beautiful”), demonstrated his belief in civic progress. As mayor (1897-1902) and U. S. senator (1915-1921), Phelan worked with the Merchants’ Association and the Chamber of Commerce in support of policies to aid San Francisco development. He traveled to Europe in 1913 as an unofficial representative of the U.S. State Department to publicize the opening of the city’s Panama Pacific International Exposition in 1914. Phelan’s elective offices set him apart from most San Francisco business leaders, but his banking, insurance, and real estate interests kept him in the thick of the city’s economic life. When silver magnate James Fair died, Phelan took his place as president of the Mutual Savings Bank. The First National Gold Bank had been organized in 1870 by the elder Phelan, who had then served as its president; after his father’s death, Phelan served as a director for the First National. Phelan’s friend, Rudolph Spreckels, son of “sugar king” Claus Spreckels, served on the board of the Mutual Savings Bank and as president of the First National. Phelan and Spreckels also shared responsibilities as chairman of the board and president, respectively, of the United Bank and Trust Company. Organized in 1923, the United Bank and Trust brought together the pioneer era Sacramento-San Joaquin Bank of Sacramento (with branches in Stockton, Oakdale, and Modesto) with the Union National Bank of Fresno and the Merchants National Bank of San Francisco. Phelan remained chairman of the board until the United merged with the Bank of America of California. Both Phelan and Spreckels continued the development of their fathers’ downtown property holdings. Phelan built offices on the choice corner bounded by Market, O’Farrell, and Stockton streets. Spreckels, president of City Investment Company, constructed an eighteen-story office building and the Strand Theater on the Market Street lots in the Claus Spreckels estate.(43)

One of the co-founders of the First National Gold Bank in 1870 along with the elder Phelan was James M. Moffitt (1827-1906). Moffitt’s son, James Kennedy, later served along with the younger Phelan on the boards of the First National and Mutual Savings. The elder Moffitt had also been a director of the Mutual Savings Bank, the First National, the Oakland Bank of Savings, and the Oakland Gas Light and Heat Company. He had helped to found Blake. Moffitt, and Company, which, after its incorporation in 1884 as Blake. Moffitt, and Towne, became the leading supplier of paper to the Pacific Coast region. The company had opened branch offices up and down the Pacific Coast and in the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys by the time James Kennedy Moffitt assumed the presidency of the firm in 1927. Like Phelan, Moffitt also served as a University of California regent.(44)

Another Phelan associate as director and president (1923–1925) of the First National Bank was John A. Hooper (1838–1925). Besides his thirty- year service as a director of the bank, Hooper presided over a half-dozen California lumber companies ranging from Port Costa in the north to San Pedro in the south. Hooper’s lumber found its way into both San Francisco and Los Angeles buildings, and he also supplied much of the construction material for the boom town of Tombstone, Arizona, in 1882. Three of Hooper’s four brothers joined him in the lumber business. One of them, Charles A. Hooper, helped to create Pittsburg, in Contra Costa County, by bringing heavy industry to the site in the form of the Columbia Steel Corporation (later a unit of U.S. Steel). His oldest daughter married Wigginton E. Creed (1877–1927), and Creed took over the presidency of Columbia Steel when his father-in-law died in 1916. A Fresno native. Creed financed his legal education at New York Law School by working as principal of the Fresno High School. After finishing his law degree, he worked in New York as secretary for pioneer California banker D. O. Mills. Like Phelan and Moffitt, Creed served as a University of California regent, but he put in a stint as president of the university as well as president of the Pacific Gas and Electric Company.(45)

Creed and Hooper socialized at the Pacific Union Club, as did another of Phelan’s fellow directors of the First National Bank, Waller S. Martin. President of a real estate management firm, Martin Investment Company, as well as of the Eastern Oregon Land Company and member of the board of Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Company, Martin was a Georgetown University graduate who lived, like many of San Francisco’s business leaders, in the suburbs. Hooper, like his neighbor financier Henry T. Scott (at whose home President McKinley stayed during his 1901 visit to San Francisco), lived in the city’s Pacific Heights neighborhood. Creed, however, lived in Piedmont across the bay, and so did Moffitt, while Phelan lived at his estate in Saratoga. Martin and Phelan both belonged to the Burlingame Country Club.(46)

In addition to his real estate and banking interests, Phelan involved himself with the insurance business, and his fellow directors of the California Pacific Title Insurance Company (formed in 1886) included John S. Drum, Emanuel S. Heller, and Jesse W. Lilienthal, Jr. Drum lived in Hillsborough, belonged to the Burlingame Country Club and the Pacific Union Club, and like Phelan was a Democrat and a Catholic. Drum devoted himself to a San Francisco law practice, then served for twenty years as a bank president, retiring from the American Trust Company in 1929. He also had interests in public utilities, serving as director of Pacific Gas and Electric and the East Bay Water Company, was a director of Columbia Steel, and sat with Martin on the board of the Eastern Oregon Land Company. In 1917, Secretary of the Treasury William Gibbs McAdoo appointed Drum head of war savings programs in California, and President Woodrow Wilson named him to one of the War Finance Corporation’s committees in 1918. He also served a term as president of the American Bankers Association (1920–1921).(47)

Notes

33. Builders of a Great City, pp. 117—118, 278 — 288.

34. Ibid., pp. 158 — 159, 172, 325.

35. Henry George, “What the Railroad Will Bring Us,” Overland Monthly 1 (Oct. 1868):302-303.

36. Decker, Fortunes and Failures, pp. 239, 233.

37. Thomas C. Cochran and William Miller, The Age of Enterprise: A Social History of Industrial America, rev. ed. (New York. 1961), p. 153.

38. Charles E. Lindblom, Politics and Markets: The Worlds Political-Economic Systems (New York, 1977), p. 172.

39. Herbert Hoover, quoted in A Man and His Friends: A Life Story of Milton H. Esberg (San Francisco, 1953), p. 121.

40. Burton W Folsom, Jr., has also used this criterion in his study of Pennsylvania business leaders; see his Urban Capitalists: Entrepreneurs and City Growth in Pennsylvania's Lackawanna and Lehigh Regions, 1800—1920 (Baltimore, 1981), p. 43. The term San Francisco business leaders includes the officers and directors of firms with San Francisco headquarters as listed in the following: Walker's Manual of California Securities and Directory of Directors, 1915 (San Francisco, 1915); Walkers Manual of Corporate Securities and Directory of Directors, 1925 (San Francisco, 1925); Walkers Directory of Directors, 1931 (San Francisco, 1931); Walkers Manual of Pacific Coast Securities, 1935 (San Francisco, 1935). References to these sources will appear as: Walkers, Allowed by the date.

41. San Francisco News, Aug. 11, 1930; San Francisco Chronicle, Sept. 29, 1937.

42. Leland W. Cutler, America Is Good to a Country Boy (Stanford, 1954), p. 126.

43. Judd Kahn, Imperial San Francisco: Politics and Planning in an American City, 1897—1906 (Lincoln, Nebr., 1979), p. 60; Bailey Millard, History of the San Francisco Bay Region, 2 vols. (Chicago, 1924), 2:10 — 11; Walkers, 1925, p. 394.

44. Who's Who in California, 1928—1929 (San Francisco, 1929), p. 521 (hereafter cited as Who's Who)', San Francisco Daily News, June 7, 1930; Neill Compton Wilson, ed., Deep Roots: The History of Blake, Moffitt, and Towne, Pioneers in Paper Since 1855 (San Francisco, 1955), p. 87.

45. Aubrey Drury, John A. Hooper and California's Robust Youth (San Francisco, 1952), pp. 25 — 26, 43—44; Lewis F. Byington and Oscar Lewis, eds., The History of San Francisco, 3 vols. (Chicago, 1931), 2:44-47; Who's Who, p. 426; Palo Alto Times, Aug. 6, 1927.

46. Walkers, 1925, p. 112; Who's Who, p. 422.

47. Walkers, 1925, p. 380; Millard, History of the San Francisco Bay Region, pp. 404 — 405; Who's Who, p. 51.

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 2 “Business and Economic Development”