California Commission of Immigration and Housing

Historical Essay

by John Baranski

This excerpt originally appeared in "Progressive Era Housing Reform," Chapter One of Housing the City by the Bay: Tenant Activism, Civil Rights, and Class Politics in San Francisco (see below for copyright and book information)

Broadway near Kearny in 1910. Eureka Hotel Building at 474 Broadway. In building at right find Cavagnaro & DeBenedetti men's clothing store.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp33.03312

In California, housing reformers continued to take a gradualist approach to involving the state in housing. Rather than seek support for broader housing reforms and programs, reformers focused instead on housing legislation at the local and state level. They used their own and the public’s anxiety about and concern for the foreign-born population to push for a state commission to work at the confluence of immigration and housing.30 San Francisco reformer Katherine Felton thought that a state immigration and housing commission with the right director could rouse “public opinion to the sentiment of preventing bad housing” and “be able to exert far more influence than a private citizen.” Otherwise, she contended, the “tremendous influence brought on building inspectors by architects and owners of property” at the local level would continue to diminish low-income housing quality.(31) Across the state, citizens pressured Republican Governor Hiram Johnson (Rep. and Prog., 1911–1917) to create a commission on immigration and housing. As one of the state’s leading progressive voices, Johnson had built a political career railing against government corruption and the monopolistic practices of the Southern Pacific Railroad, while still putting his faith in government to further the general welfare. In 1913, he responded with the creation of the California Commission of Immigration and Housing (CCIH), which expanded the state’s regulatory role in housing.(32)

The CCIH leadership and staff worked at several levels. Johnson appointed Simon Lubin—a progressive businessman, economist, and reformer—to run the commission, a post he held for ten years. Nearly all of the new agency’s staff came from housing and planning organizations around the state. The CCIH staff tried to improve the living and working conditions of workers in the state in part to reduce the growing number of strikes, especially those waged by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and immigrants. CCIH efforts often involved both collaborating with and coercing employers to provide better housing, edible food, and higher wages. Meanwhile, the CCIH worked to Americanize immigrants through English and civics classes.(33)

Lubin and the commissioners collaborated with local reformers to produce surveys of urban and rural housing. As a result, the CCIH became a clearinghouse, both collecting and distributing this local research and information coming out of national and international housing circles. The CCIH’s dissemination of this knowledge helped educate the public about housing problems and solutions, which in turn led to tougher state housing laws—but the CCIH still lacked the funding required to follow up on housing violations. Even in 1923, the CCIH only had three inspectors for the entire state, far fewer than the twenty the CCIH director believed were necessary for San Francisco alone. Not surprisingly, the state’s low-rent housing remained substandard and inadequate to meet the population’s needs.(34)

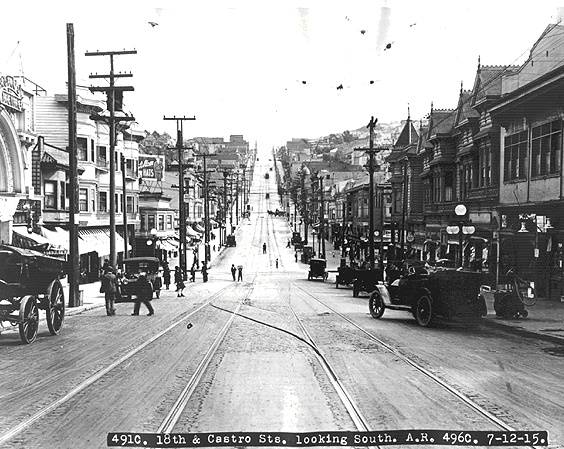

18th and Castro looking south, July 12, 1915.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

Besides the CCIH, San Francisco’s housing reformers looked to the 1915 Panama–Pacific International Exposition as an opportunity to build support for their efforts. Held in San Francisco, the world’s fair became a venue to raise public support for housing and social policies. Planning for the fair, commemorating the opening of the Panama Canal, had begun in 1904. Working through the San Francisco Civic League of Improvement, the city’s leaders hoped to showcase new products and the value of private–public partnerships to civic unity. After the 1906 earthquake and fire, they also wanted to show the world that their city had not only recovered but remained the cultural and financial center of the Pacific Rim. Nearly a third of the city’s 450,000 residents turned out for opening day, and, in the next 288 days, 15 million visitors passed through the gates into a constructed world with sights common to world’s fairs: corporate promotions of goods and gadgets; replicas of classical Roman buildings; a 120-foot golden Buddha statue; gaudy, racist simulations of indigenous villages from Africa, Asia, and the Americas; and a “Race Betterment” booth sponsored by California’s eugenicists.(35)

The 1915 exposition also included less carnivalesque exhibits, such as displays of social surveys and promotions of public health, transportation, utilities, and even planning of industrial and agricultural resources. Labor experts presented information on how to improve the economic security of workers through higher wages, cooperative insurance and banks, and various kinds of social insurance. For their part, housing reformers promoted regulatory legislation, cooperative housing, and establishing local offices to build government housing.(36) These displays of social policy alternatives to classical liberal economic practices aimed to expand economic rights and security connected to citizenship—and although they did not lead to a burst of housing and social legislation in San Francisco, their presence did make city-owned projects easier to justify.

With direction from Mayor James Rolph (Rep., 1912–1931), a banker and businessman, the city built a new civic center based partly on the Burnham plan, including a new City Hall to replace the one destroyed in 1906. San Francisco’s government purchased the city’s railway system and became the first municipality in the nation to own its transportation system. San Francisco also began planning the construction of the Hetch Hetchy reservoir, which promised to fill a beautiful valley with water in order to provide the city with a public alternative to the water monopoly held by the Spring Valley Water Company. With federal assistance and city bonds, Rolph moved these municipal projects forward. The projects reflected the demands from local progressive and radical organizations, such as the Bay Area’s Public Ownership Association, for greater government control of sectors of the economy.(37)

previous article • continue reading

Notes

31. Katherine Felton to Simon Lubin (November 25, 1912, and December 16, 1912), Folder “Felton, Katherine,” Box 2, Simon Lubin Papers, BANC. Quote in November 25, 1912, letter. Also see Ziegler-McPherson, Americanization in the States.

32. CCIH, First Annual Report, An A-B-C of Housing (1915), and A Plan for a Housing Survey (1916); Simon Lubin Papers, especially Box 3, BANC; Ziegler-McPherson, Americanization in the States; Deverell and Sitton, California Progressivism Revisited; Sanchez, Becoming Mexican American. Johnson also created California’s Industrial Accident Commission and the Industrial Welfare Commission.

33. CCIH, First Annual Report, An A-B-C of Housing, and A Plan for a Housing Survey; Ziegler-McPherson, Americanization in the States; Deverell and Sitton, California Progressivism Revisited. Lubin led the investigation into a 1913 IWW strike waged for better food, housing, and wages at Durst Ranch in Wheatland, California that turned violent when local authorities arrived. See Ziegler-McPherson, Americanization in the States; Melvyn Dubofsky, We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World (Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1969); 294–302; Dino Cinel, From Italy to San Francisco: The Immigrant Experience (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1982), 243–45; Simon Lubin Papers, especially Box 3, BANC.

34. In 1923, the CCIH director thought Los Angeles needed thirty inspectors. State Director to Mr. A. S. Hoff, President of SF Local Painters Union #19 (April 6, 1923), Folder “General Correspondence H, 1923–24,” Carton 40, CA Department of Industrial Relations, BANC. CCIH, First Annual Report; Ziegler-McPherson, Americanization in the States; Stephanie S. Pincetl, Transforming California: A Political History of Land Use and Development (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), chapters 2–3.

35. Chicago leaders used the 1893 World’s Fair to show how their city came back after the 1871 fire. The Improver: The Monthly Magazine for the Advancement of San Francisco (August 1912), CHS; Pamphlets in Folder “Materials Concerning Exhibits, Grounds, and Services,” Panama–Pacific International Exposition, BANC; Frank Morton Todd, The Story of the Exposition, vol. II (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, Knickerbocker Press, 1921); Issel and Cherny, San Francisco, 166–69; Abigail M. Markwyn, Empress San Francisco: The Pacific Rim, the Great West, and California at the Panama–Pacific International Exposition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014).

36. The Improver: The Monthly Magazine for the Advancement of San Francisco (August 1912); Pamphlets in Folder “Materials Concerning Exhibits, Grounds, and Services,” Panama–Pacific International Exposition, BANC; Issel and Cherny, San Francisco; Markwyn, Empress San Francisco.

37. See Folder “Public Ownership Association,” Carton 14, San Francisco Labor Council Records, BANC; Anthony Perles, The People’s Railway: The History of the Municipal Railway of San Francisco (Glendale: Interurban Press, 1981); Issel and Cherny, San Francisco, 176–79, 210.

Excerpted from Housing the City by the Bay: Tenant Activism, Civil Rights, and Class Politics in San Francisco by John Baranski, published by Stanford University Press. Used by permission. © Copyright 2019 by John Baranski. All rights reserved.