Jimbo's Bop City

Historical Essay

by Carol Chamberland

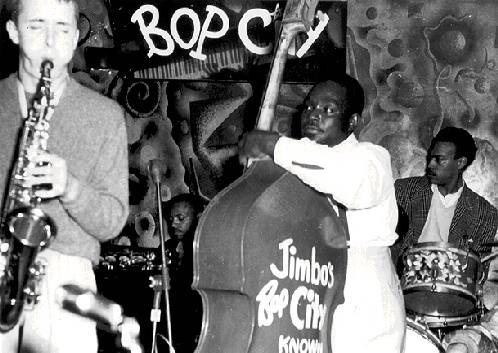

Wailing at Cousin Jimbo's in the 1950's. Vince Wallace on sax, Frank Jackson on piano, Alfred 'Smitty' Smith on drums, "Bear" on bass.

Photo: Jimbo, via Carol Chamberland

Opened up to the public from 2:00 to 6:00 AM, musicians were admitted free, but everyone else had to pay $1. Jimbo continues: "So then I got me a neon sign and put it out there and everybody started coming. In the meantime, me and Billy Eckstine was friends. And I got him to come and hang out in my little joint. And after Billy Eckstine made it, then here come Miles [Davis]. Here come Diz (Dizzy Gillespie], And here come Charlie Parker."'

Jimbo's Bop City on Post Street, c. 1959.

Photo: Phil Palmer

On the outside at 1690 Post Street, loud signs proclaimed that bebop lived here. At the brightly painted entrance were double doors; one led to the minuscule cafe, the other into Bop City itself. Jimbo sat at the entrance to the back room, collecting one dollar per person, except from musicians. If your attitude wasn't right, you didn't get in, dollar or no. Jimbo ran a tight ship. That's why no one I've spoken with can ever remember any fights or problems in Bop City. Problems were ejected from the inner sanctum, swiftly and permanently...

With compassion, dignity and diligence, Jimbo maintained a unique climate within his domain. Black discrimination against white players occasionally became an issue on the bandstand, but Jimbo tolerated no racial discrimination whatsoever in his establishment, a rule that he vigorously enforced in those days, and by which he still abides today. At Jimbo's Bop City, the intense music served as a binding agent, uniting the audience and musicians in a shared passion that transcended ethnic considerations. Vocalist Bobbe Norris recalls her days as a young, attractive, white woman at Bop City. "We really had a good scene. People weren't prejudiced, there wasn't any of that going on. It was just like you were either good or you were bad. And that was how people judged you. I never felt the color thing or any of that. I was just accepted as a singer and a young person who was talented. And that was wonderful."

Singer Mary Stallings comments on the jazz they were playing at Bop City, from her black perspective: "It's such a spiritual music, it really binds people together. And for that time, people that had any kind of prejudice or any kind of hang-ups, they don't even feel it. They'll sit next to each other, drink out of the same glass and won't feel a thing. I mean, that's from the heart."

Patricia Nacey sums it up nicely: "Jimbo's was more than just a place to gather to hear great sounds. It was like a snapshot of your soul or a snapshot of the soul of the community. I think in the early dawn of the civil rights movement, it was 3:00 AM at Jimbo's."

It was even earlier in the dawn of the women's liberation movement—the 1950s jazz scene was a boys club if ever there was one. Most of the female population at Bop City was in the audience. Some were students and waitresses, some were working girls, and others were aspiring singers. At one time or another, all the top female jazz singers in America made it to Jimbo's Bop City, including Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Dinah Washington, and Sarah Vaughn. But relatively few women instrumentalists were to be seen and heard in the jam sessions.

The Fall

Jimbo Edwards tells how he experienced the end of that era: "The time had ran out. I was there fifteen years from 1950 to 1965 and the time was over. It was all over. The Blackhawk was closed. The Say When was closed. All the clubs was closed and the musicians didn't come to San Francisco. So then I was sitting with an empty club and nobody to draw from."...

Jimbo's Bop City closed its doors in 1965, just when the Fillmore entered a period of drastic physical change.

—Excerpted from "The House That Bop Built" by Carol Chamberland, from California History Magazine, Spring 1997