LABOR & YERBA BUENA CENTER

Historical Essay

by Chester Hartman

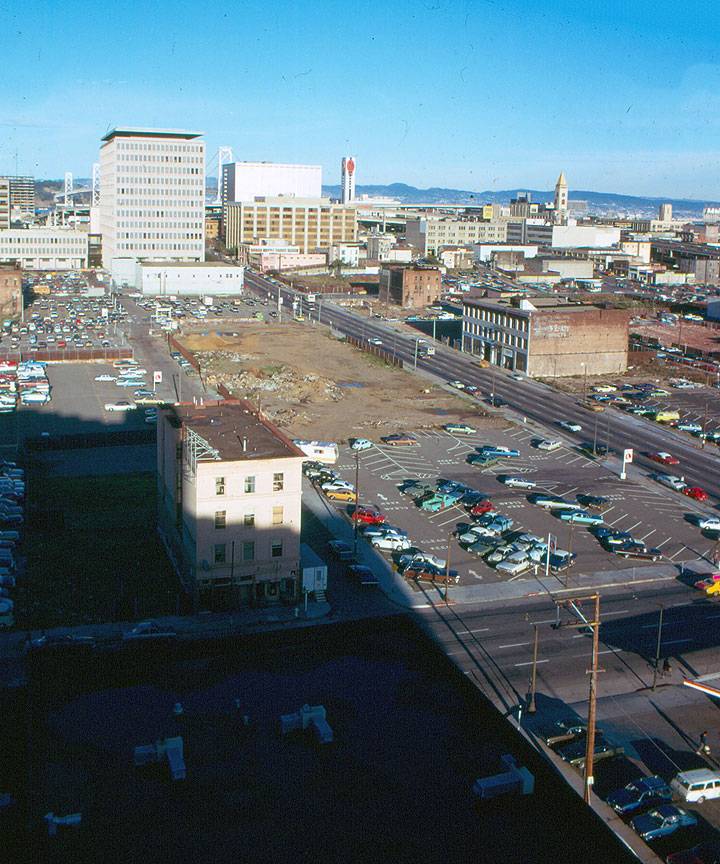

Future site of Yerba Buena Gardens in a 1976 view from above 4th Street looking east along Folsom.

Photo: Francisco FloresLanda

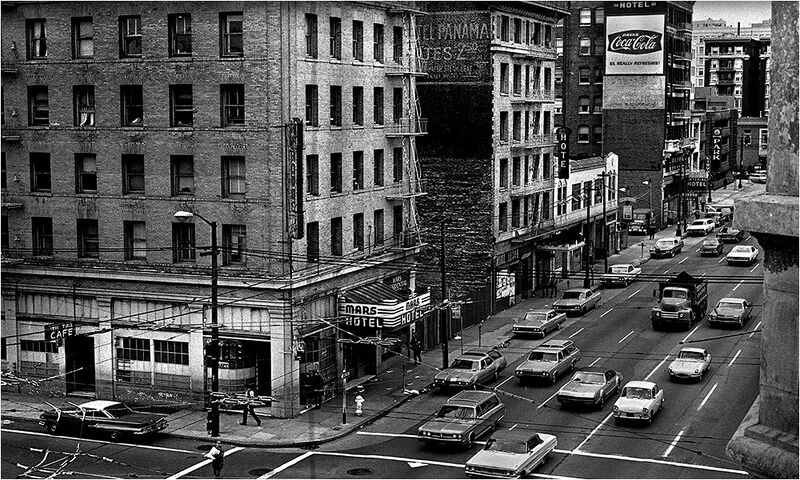

Mars Hotel at northwest corner of 4th and Howard, c. 1968.

Photo: © Ted Kurihara

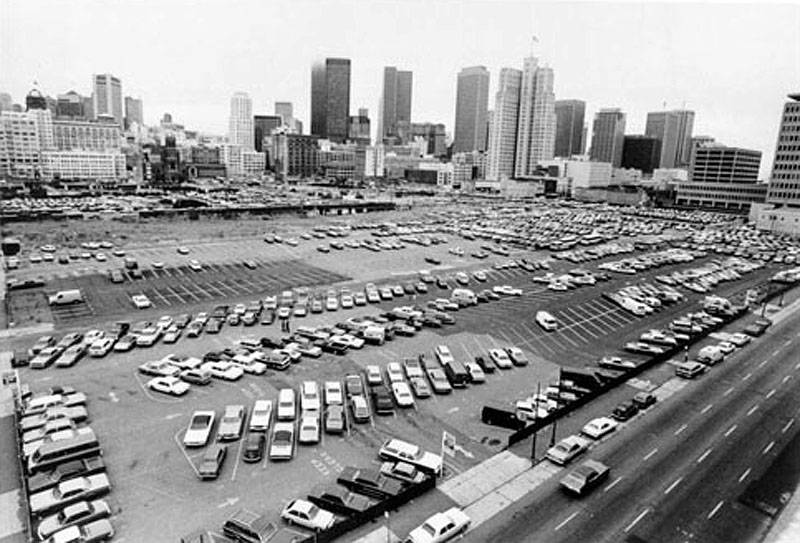

Yerba Buena cleared, early 1970s.

Photo: Tim Drescher

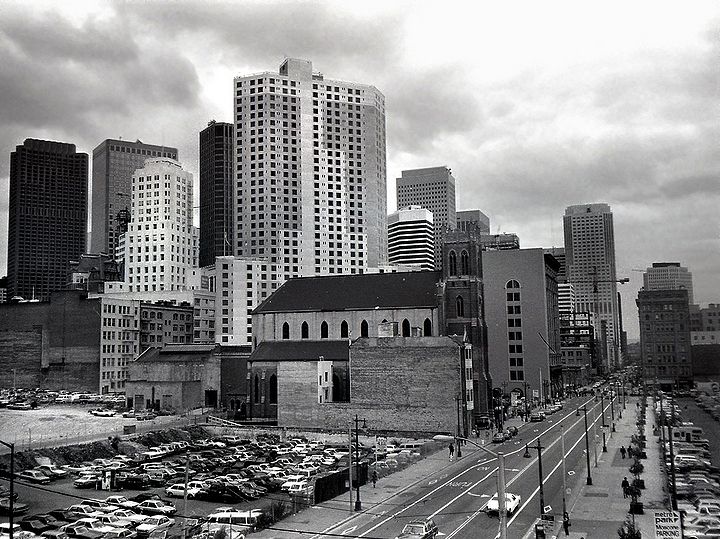

Looking eastward across the Yerba Buena Gardens, 1998, St. Patrick's at left, SF Museum of Modern Art squats in front of the 1926 Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Building in the middle of the photo.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

New 21st century construction is beginning to dwarf the SF Museum of Modern Art.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

| Although initially opposed to the building of the Yerba Buena Center, beginning with the election of Joe Alioto in 1967, labor became a strong proponent of redevelopment in the central district of San Francisco. Labor leaders, especially those of the ILWU and the Building Trades increasingly backed redevelopment for their own economic future even at the cost of replacing older members, as they saw the transformation of San Francisco from a blue-collar industrial city to a white-collar administrative center as inevitable. |

Organized labor's strong backing of Joe Alioto in 1967, followed by its strong backing for Yerba Buena Center, was a dramatic reversal of its original stance toward the project. Businesses in the South of Market area were highly unionized, and when redevelopment plans first came to light, the San Francisco Central Labor Council, AFL-CIO, opposed them on the basis that the development would displace thousands of blue-collar jobs and replace them with nonunion clerical and service workers.

In the early and mid-1960s, labor leadership generally had expressed great reservations about the type of economic development being pushed by the Bay Area Council, the Blyth-Zellerbach Committee, and SPUR. The April 14, 1963, Chronicle reported a statement issued by local AFL-CIO and Teamster leaders, which asserted: "It may suit the purpose of some to make San Francisco a financial and service center, but it destroys the jobs of working people and weakens the City's economic foundations."

In the November 3, 1965, Official Bulletin of the San Francisco Labor Council, Secretary-Treasurer George Johns took a broad look at the YBC project, the Redevelopment Agency, and the interests served by urban renewal in San Francisco, It was the first truly incisive public critique of this downtown development:

"Speculative real estate operators ... seem to have taken over the planning functions of our City ... Convention halls and sports arenas have their place. But the loss of millions of square feet of industrial space can only extend unemployment, suffering and poverty ... A redevelopment program is certainly needed there [South of Market]. However . . . a rehabilitation and conservation program makes far better sense than the program of massive clearance....

Certain politically important persons consider the clearance program in Yerba Buena as the beginning of the redevelopment of 1100 industrially zoned acres South of Market. With the support and blessings of the [Redevelopment] agency, they are ready to kick industry out of San Francisco....

In addition to the many workers who will lose their jobs, we wonder if the policy makers of this City have thought of the social and economic effect on over 3,000 single persons, a third of them aged, who will be displaced in the area without realistic provision for relocation. Displacement can mean higher rent and out of the way locations. The hardship such conditions will impose on senior citizens is obvious enough to anyone still sensitive to human needs. . . .

Yet citizens who oppose a policy of rezoning light industry right out of the City are considered "obstructionists." Obstructionism, in fact, has generally become a dirty word for anyone bucking the policies of the redevelopment agency. But isn't it the agency that is really obstructing? Aren't they obstructing efforts to retain industry and therefore jobs in San Francisco by moving away from the preservation and expansion of industrial zoning that is so necessary if we are to maintain the economic balance of this City and the continuance of job opportunities?

What they are not obstructing are the special interests of certain groups. The Agency and Mr. Herman must be reminded of their obligations to the rest of the citizens of San Francisco. The Yerba Buena issue is a good place to start."

But as time passed, and the various pieces began falling into place, pressures began building within labor ranks and from outside for a reversal of labor's position on YBC. The politics of the Alioto campaign and election was one major element in the switch. Justin Herman and other SFRA representatives courted labor leaders, trying to convince them that the loss of blue-collar jobs and the transformation of the city into a white-collar administrative center was inevitable, and that labor could reap certain gains from this process. In a short time the conversion was complete.

Yerba Buena area, 1976, looking northeast from apx. 4th and Folsom, St. Patrick's Catholic Church in middle on Mission Street where it remains in 2013.

Photo: Francisco FloresLanda

Photo looking east from 4th and Mission, 1984.

Photo: Dave Glass

Looking northeast from apx. 4th and Folsom, 1977.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Within the Labor Council, it was the Building and Construction Trades Council (BCTC) that carried the day for YBC. The conversion of downtown San Francisco into the administrative and financial headquarters of the West--particularly through the massive Bay Area Rapid Transit System and the Golden Gateway project--had been good for the various trades and locals in the construction industry. By the mid-1960s the BCTC was a backer not just of Yerba Buena Center, but of any planned construction which would provide employment for members of its affiliated unions. This included the proposed 550-foot U.S. Steel highrise on the waterfront and a proposed freeway through Golden Gate Park, both of which earned the hostility of the general populace because of the loss of recreational space and scenic views. But as a representative of the BCTC said regarding Yerba Buena Center, "We are in favor of building with no respect to where it is and how it is."34 For many San Francisco workers the quest for construction jobs was vital to survival. The redevelopment master plan for the city was displacing thousands of jobs, and it was not likely that unemployed bluecollar workers would find employment in white-collar jobs.

"[U]nion leaders usually agree to whatever projects are proposed by business--just as long as the projects provide jobs.... It ... has been rare for union leaders to question financial returns promised to business from proposed projects; they merely agree they should be as large as possible to maximize the share granted their members. .. . Unions merely react to the doings of others, occasionally forcing them to alter their plans after they have been unveiled but usually playing only the role of important supporter."

A critic put it this way: "The unions are an arm of the downtown establishment, playing pretty much of an establishment game. They stand by while business dictates the course of San Francisco and, as long as they get theirs, they don't rock the boat."

Typical South of Market alley, 1976.

Photo by Francisco FloresLanda

Along with the construction trades, the Bartender and Culinary Workers and Cooks unions, who had much to gain from more hotel and entertainment facilities, joined the chorus of YBC supporters. The ILWU's strong support of the project is at least partially explainable by the union's concerns for its future. The ILWU has a historic reputation as one of the most progressive unions in the country, having readily taken such stands as supporting the civil rights movement and opposing the Vietnam War. With growing mechanization of the West Coast docks, the ILWU was forced to face the prospect of slowly dying or merging with a larger union, such as the International Longshoremen's Association, dominant on East Coast and Gulf docks, or the Teamsters, who were handling increasing quantities of containerized cargo. ILWU leadership therefore saw it in their best interest to generate more jobs by backing business and political forces determined to advance San Francisco and the Bay Area as a service and trading hub for the Pacific Rim. As union membership declined, the old guard in leadership moved to protect its position by becoming a direct participant in the city's political machine, and thus consolidated its power around the union's steadily employed members.

Labor support for clearance in South of Market was not without its irony. Many of the area's retired residents had once been active union members, organizers, and even officials, and were supplementing their Social Security with union pensions. Yet the union leaders were insensitive to the plight of the older men, classifying them as "winos and bums." As one union leader put it: "They poor-mouth a lot, but under our system the residents can't remain. A few can't hold up progress."

But more than a few were doing their best to hold up "progress." The South of Market residents were to form an organization called Tenants and Owners in Opposition to Redevelopment (TOOR) to fight for their rights in the face of the displacement threat. Organized labor's break with its former constituency and membership, and its new ties to the Alioto administration and its downtown growth policies, led it to go so far as to file a "friend of the court" brief defending the Redevelopment Agency against charges of inadequate relocation brought in federal court by the South of Market residents.

--Chester Hartman, The Transformation of San Francisco