Levi's Plaza

Historical Essay

This article was originally in The Semaphore #199 in 2011.

By Art Peterson

View west towards Coit Tower and Telegraph Hill from Levi's Plaza, 2012.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Levi's Plaza from Filbert Steps, 1999.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The Levi Strauss Company has been a part of San Francisco life since the 1870s, but it’s only since 1981 that it’s been below Telegraph Hill. What happened then was the privately-owned firm hired HOK and Gensler Architects to create a building that fits into the neighborhood rather than dominates it. The set-back layers of the company’s headquarters don’t scream corporate monolith. The building makes a point of not intruding on the Coit Tower/Telegraph hill cityscape. The surfaces echo the texture of the historic Italian Swiss colony building just to the north.

Levi’s Plaza is a great place to eat lunch. The plaza is the handiwork Lawrence Halprin, the tribal leader of American landscape architects, who died in 2009 at age 93. Halprin was responsible for huge parts of San Francisco’s public space: Ghirardelli Square, United Nations Plaza, Justin Herman Plaza, the landscaping at the Lucas Digital Arts Center in the Presidio, and the renovation of Sigmund Stern Grove. In the 1950s, Halprin even had a hand in the redesign of our own Washington Square Park proposing the elimination the historic crisscross pattern, an idea adapted by the architects that took over the job.

When Halprin went to work on the Levi’s project in 1982, he was told by the Hass family, heirs to the Levi Strauss brand, “monumental is not our style.” Halprin had no problem with that dictum. Yes, the plaza west of 1150 Battery Street, with its inlaid red, gray, and white granite blocks divided into 35-foot square diamonds, shares characteristics with the grand plazas of Europe. But the Plaza is a canvas for the square’s dramatic punctuations: the wide spreading trees, the heroically sized granite stones—many chosen by Halprin from the same quarry he used to pick rocks for his Franklin D. Roosevelt Monument in Washington D.C., the fountain which incorporates these craggy rocks into its structure, and the continuing sound of water, providing tranquil white noise for those wishing to escape the harsh sounds of the city.

(top) front of the headquarters building; (middle) plaque on walking stones in plaza; (bottom) south facade of old Italian Swiss Colony building, integrated into the complex.

Photos: Chris Carlsson

East of Battery Street, the park loses it hard edge and turns soft. Halprin said this area was a homage to the Sierra foothills business beginnings of Levi Strauss. The key features now are soft rolling green hills, pine and willow trees and more water and granite, but they are integrated in a stream that suggests California’s mountain terrain before it takes a whimsical turn toward a Japanese garden complete with bridge.

It’s worth noting that some these features provide “attractive nuisances” that would not be allowed in a city-owned park. Levi Strauss does not need to answer to bureaucratic strictures and provides 24-hour security to guard against mishaps. The company did not quibble when Halprin’s plans went $4 million over budget and the firm has made provisions to maintain the park in perpetuity. In an era when examples of corporate greed and malfeasance scream daily from the headlines, it’s appropriate that we pause in appreciation of the company and the great landscaper who have given us this most beautiful of public-private city spaces.

Bucolic scenes from east side of Battery Street where the willows and water predominate.

Photos: Chris Carlsson

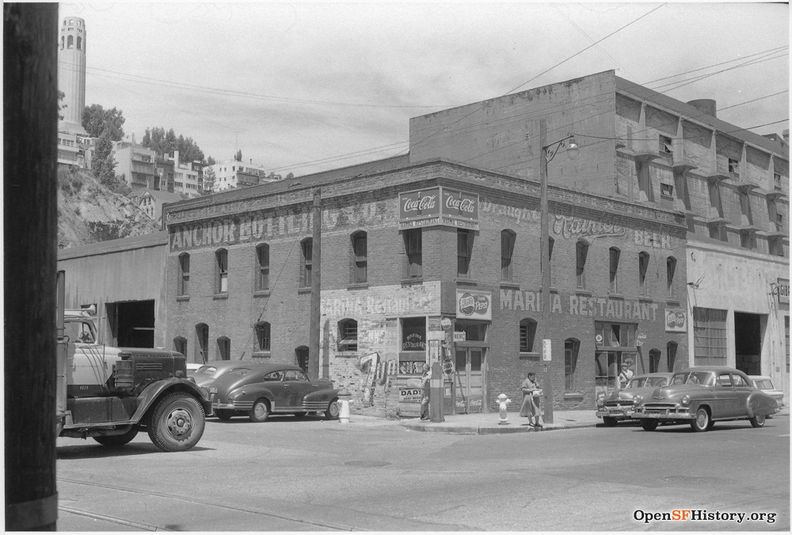

The complex also includes rehabilitated warehouses nearby—the 1903 Italian Swiss Colony Building and the 1879 Cargo West Building at Battery and Union.

1105 Battery on northwest corner of Battery and Union, May 1959. San Francisco Landmark No. 104, Independent Wood Company, seen here as Marina Restaurant. This building is now surrounded by Levi's Plaza.

Photo: OpenSFHistory, wnp27.50230