Sailor's Union of the Pacific

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

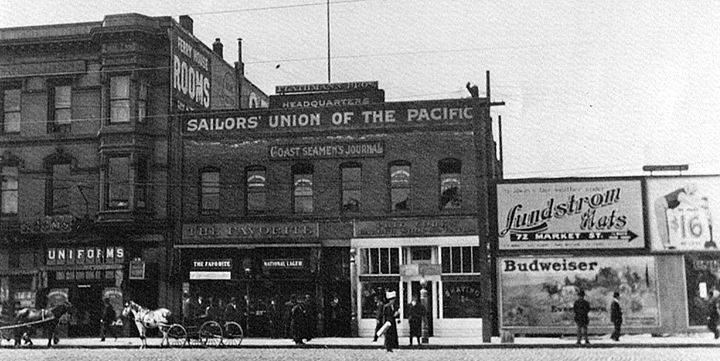

Sailors Union of the Pacific building along the waterfront in the 1880s.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

In the mid-1880s, sailors were the mobile industrial workforce that made the local and global economy possible. The Port of San Francisco was by far the largest on the west coast and many more ships called at its docks than anywhere else. The men who sailed the seas and the coastal trade were indispensable, and supplying sailors to ships was a thriving business. A peculiar system sprung up to combat the perpetual shortage of able-bodied seamen available to ship out, run by boarding house and brothel owners known as “crimps.” As ships pulled into harbor the sailors on board would be inundated by offers of places to stay, free drinks and meals, and promises of sexual delights. After months at sea, most seamen were ready to let loose and the local businessmen knew how to take full advantage of them.

If, upon arrival, you began drinking and didn't stop for a couple of days, it wasn't unusual to awake from a major drinking binge to find yourself once again at sea. Sometimes San Francisco's visitors or bank clerks or draymen might find themselves out along the Pacific Avenue “Barbary Coast” seeking pleasure and a stiff drink, only to wake up the next day at sea. Lack of experience or skills was less important than being simply alive and mobile because once you were at sea you had no rights. You had been “shanghaiied.” Someone had signed a document in your name, usually the bar or hotel owner or “crimp,” in exchange for payment of whatever bill you may have run up in their establishment (calculated of course at exorbitant rates), plus a bonus.

The labor historian Ira B. Cross, in his article on "First Coast Seamen's Unions" published in 1908, declared "it is impossible to do justice to the brutality shown to the sailors in those days." Along with the reign of cruel "bucko" mates and masters, the seamen were afflicted with a legal status that made them virtual slaves. At sea, seamen were under the complete control of the ship captain, a system that was upheld in an 1897 U.S. Supreme Court decision Robertson v. Baldwin: “The court excluded civilian sailors on merchant ships from the 13th Amendment's protection against involuntary servitude with the extraordinary rationale that Seamen are . . . deficient in that full and intelligent responsibility for their acts that is accredited to ordinary adults, and therefore must be protected from themselves in the same sense in which minors and wards are entitled to the protection of their parents and guardians.”

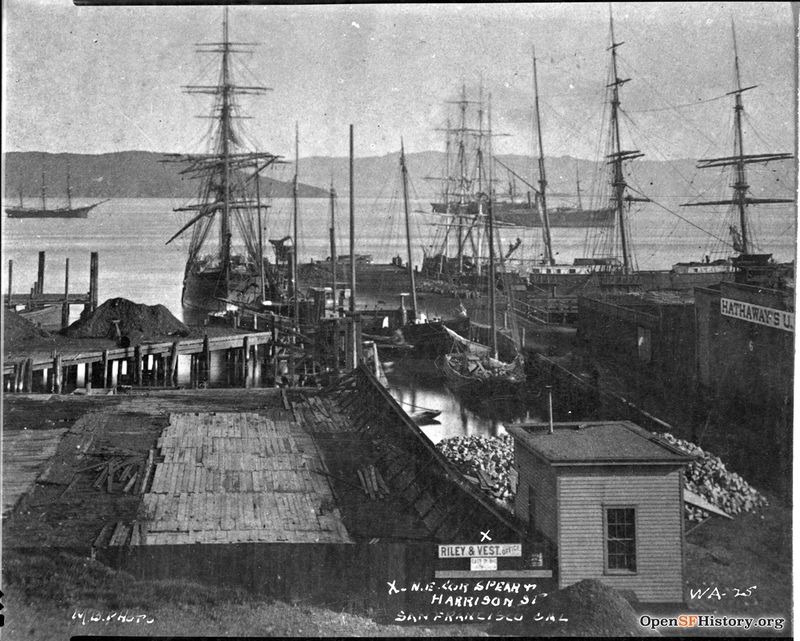

Spear and Harrison piers, 1860s, a short distance from where the Coast Seamen's Union was founded in 1885.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp71.2174

In the face of this system, seamen began to organize their first union, the Coast Seamen's Union. Burnette Haskell was one of the early organizers, a fascinating radical lawyer who had attended the International Workingmen's Association convention and returned to organize a local committee of the organization. Exhorting sailors from a soapbox along the waterfront between Howard and Harrison, Haskell helped to attract a couple of thousand sailors to launch the union. The Coast Seamen's Union was founded on March 6, 1885, with a call for labor organization—the "Sailors' Declaration of Independence"—from a lumber pile on the Folsom Street Wharf in San Francisco. The dour Norwegian Andrew Furuseth became its early leader, and after merging with the Steamship Sailors a few years later it was renamed “The Sailors Union of the Pacific” in 1890 and remains alive today.

Andrew Furuseth, Senator Robert LaFollette, and muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens.

It was Furuseth's tireless efforts to change the legal environment that finally led to the federal Seamen's Act of 1915 becoming law, which put an end to the routine violence on ships, and granted new rights to sailors in port too. Just a few years later, though, soon after WWI, an employer counter-attack virtually broke the union by 1921. A California Sedition Act made any association with radical ideas (this just after the Russian Revolution) subject to fines and imprisonment for union leaders, which prompted Furuseth to lead an aggressive purge of his own union, firing all radicals associated with either the anarchistic Industrial Workers of the World, or pro-Soviet Union Bolshevism. After a decade under the thumb of “fink halls” and the bluebook system of company unions, the seamen joined together with the longshoremen in 1934 to stage the epic waterfront strike that shifted labor relations in San Francisco for good, and re-established the Sailors Union of the Pacific as the legitimate representative of the sailors.