When the Committee Was in Session

Historical Essay

by Art Peterson, originally published in The Semaphore #205, Spring 2014

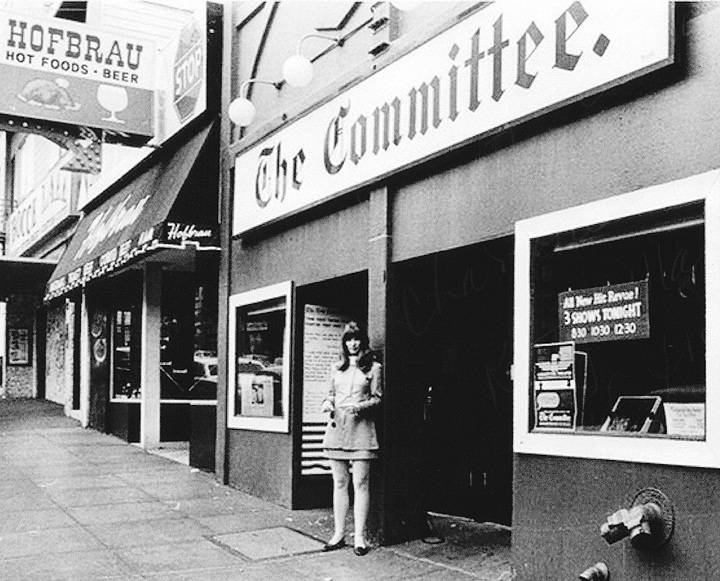

Barbara Bosson in front of The Committee Theater at 622 Broadway, circa 1967.

Photo: courtesy Sam Shaw

The late, venerated San Francisco Chronicle culture critic John L. Wasserman was a man not given to unstinting praise. So when, in the late 1960s, he said of The Committee, the improvisational comedy group that had taken up residence at 622 Broadway in 1963, that it included “the most creative group of people the city has ever seen,” you can be sure that he meant it.

Such praise was probably more than Alan Myerson could have expected, when, as a member of Chicago’s groundbreaking improv group, Second City, he came west with a young crew of comics. There were five of them—average age 23—joined by the then-emerging San Francisco Renaissance man Scott Beach, who at 32 was the company’s graybeard.

Sam Shaw, the founder and director of the San Francisco Improv Festival, and his partner Jamie Wright are making a film about the group, “The Committee—A Secret History of American Comedy.” Shaw says that Myerson came west specifically to create a more politically based improv form, rather than duplicate the observational humor that was the Second City’s forte.

Myerson arrived at the right place at the right time. Making the rounds of the cocktail party circuit inhabited by the Bay Area intelligentsia, he pitched his project. Prominent psychiatrists and stars of the UC Berkeley faculty became his backers, allowing the newly formed group to take up residence in a 300-seat theater at the former Italian club, the Bocce Ball. The San Francisco writer Herb Gold, another of the backers, remembers the early audiences as being a collection of “hangers out, college kids, old beatniks and liberal dentists.”

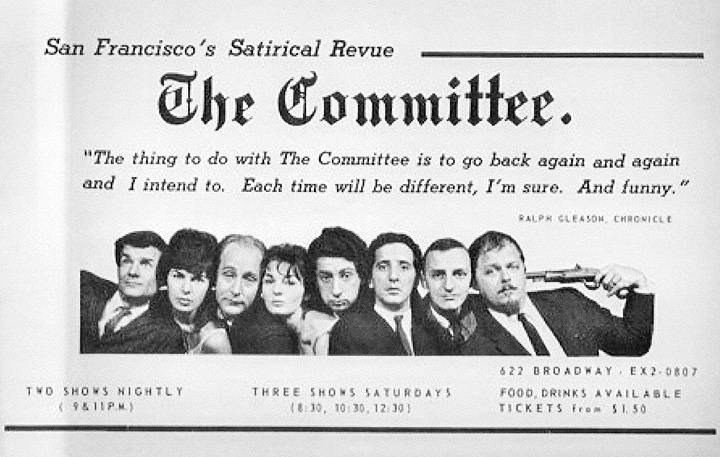

Promo art for The Committee original revue with the first cast.

Image: courtesy of Sam Shaw

Then the word got out. The edgy comedy The Committee was offering melded perfectly with the early ’60s San Francisco zeitgeist. Original cast member Larry Hankin remembers when, one Saturday night, he was urged by a fellow cast member to come outside the club, and “there was a freakin’ line around the block and it was like that like every Saturday night from then on.” The group was soon doing 13 shows a week. The investors were handsomely rewarded and the actors, who were stockholders in the venture, were in the top 10 percent of Actors’ Equity earners.

The performers were loving what they were doing, but it was hard work. “We rehearse all day and perform all night,” was the common gripe delivered with a smile.

What the cast members were creating was something akin to jazz, particularly in the 20 minutes of grooving on themes that grew from audience suggestions following the one hour of semi-prepared skits. There was a parlor-game quality to these segments that audiences found involving. In one format, the audience would suggest a word and the troupe would pick up on it, each, in turn, introducing a new word with the last letter of the previous one. When an audience member yelled out “stop,” the drama began, using that word as a starting point.

The actors needed to stay nimble. The newspapers were required reading. Myerson recognized that “things that were pertinent a month ago, are not necessarily pertinent now.” “The trick,” said cast member Don Sturdy, “is never to plan anything in detail.” “Improv is like Russian roulette,” Scott Beach added.

While politics was very much front and center, a revisit to the sketches from that period would provide a time capsule insight into life in the ’60s: there were pieces about encounter groups, wife swapping, litterbugs and horror movies. Audience members, who never quite got the pantomime of the French mime Marcel Marceau, could find solace in a performance delivered by a Marceau stand in, silently portraying pain, fear, love and anguish, all with the same expression.

The performances often ended with a group musical, sometimes with a political bent. For instance, an aria drawing on Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, with references to insecticides and detergents, but at other times the musical finale would take the form of a mock Italian opera with everyone dead at the final curtain.

The Committee’s main mission was to afflict the comfortable. In one skit, a governor, prison chaplain and prison warden are sympathetically wringing their hands about the fate of a prisoner about to be executed. When the electric chair goes on the fritz, the trio beat the man to death by hand. Some of their routines—like two “sportscasters” doing a play-by–play of a battle in the Mekong Delta, were dismissed by critics such as Stanley Eichelbaum of the Examiner as “preaching to the choir.” Still, these segments gave the choir fodder to engage in their own preaching.

The group’s members were also activists outside the theater. When anti-Vietnam rallies took place on the UC Berkeley campus in 1964, The Committee was there along with Joan Baez and Dick Gregory. In 1968, Myerson was arrested for demonstrating at Santa Rita prison. “Jails exist to absolve people of responsibility,” he believed.

By the mid–’60s, The Committee had spread its wings. It opened a theater on the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles (where most of its surviving members live today). They had gigs in venues as disparate as Berlin and Austin, Texas. They had a run in New York, overcoming what their producer, Arthur Cantor, called that city’s “reliance on tax-deductible people, tourists and prices that kept out the younger crowd.” In one of those bursts of entrepreneurial creativity that characterized the group, they ran up against New York’s regulations forbidding them to sell alcohol in a theater. They solved the problem by giving booze away. The group also ventured into television, performing on the “Flip Wilson Show” and many times on the “Dick Cavett Show.” Before its demise in 1973, it is estimated that The Committee had performed before 5 million people, including a 1966 “Satirathon” at the Broadway venue in which 3,000 people were admitted in shifts until the remaining disappointed line-standers had to be sent away at 6 o’clock in the morning.

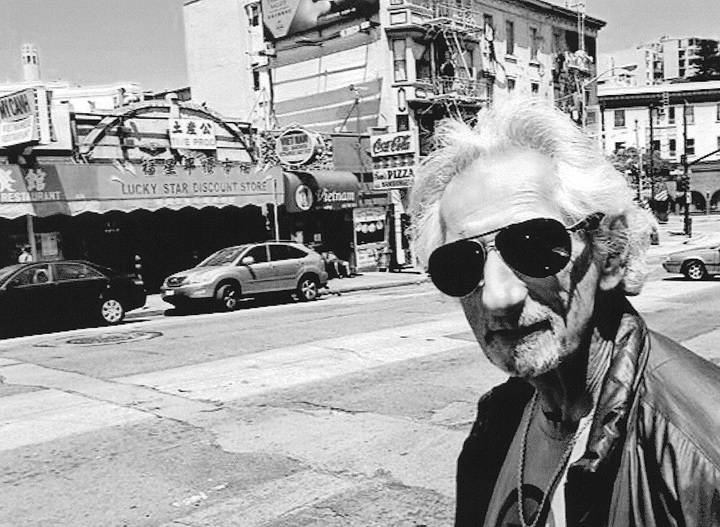

Larry Hankin in front of 622 Broadway in 2012.

Photograph by Jamie Wright

During its nine-year run, The Committee turned in new directions. Shaw believes that the group took a turn from “civil rights to more drug-oriented material,” which seemed to mirror a change in the direction of society. Two suburban housewives, for instance, were cast in an LSD-inspired dialogue.

The major change, however, was the group’s adoption of “the long forum,” known, for debatable and obscure reasons, as “The Harold.” The Harold was improv without a net. A suggested word from the audience, say “Cuisinart,” might lead to an unplanned set-up involving an incompetent Cuisinart repairman that would embark the players on a 45-minute adventure in communication and miscommunication. Done badly, of course, this can be taxing for spectators. Shaw believed that done well, the form allowed audiences to see the creative process at work in a way that other art forms did not.

By 1969, some think The Committee had lost its political edge. Myerson said that “now politics is too frightening for satire.” Larry Hankin added, “We can’t attack the sacred cows any more because the sacred cows are attacking each other.” At any rate, it was difficult to make fun of the slaughters in Vietnam and Biafra.

The group was losing money by the ’70s, the audience was declining and there was somewhat of a consensus that the improv form had become stale.

The shuttering of The Committee says nothing about the importance of the group in the history of American comedy. Most all of its members went on to significant second acts. Carl Gottleib was to write the great American comedy, The Jerk. Gary Goodrow has had credit in more than 50 films, and, perhaps most significantly, a key role in the 1973 production of The National Lampoon’s Lemmings at New York’s Village Gate where he worked with the then-undiscovered John Belushi and Chevy Chase. This production Shaw sees as establishing a direct connection between the revolutionary work of The Committee and the emergence of “Saturday Night Live.”

An even more direct connection to SNL can be seen in the career of Del Close, the “mad scientist” director of The Committee in the mid-’60s. After leaving The Committee, he returned to Chicago and in the years following became the “house metaphysician” for “Saturday Night Live,” coaching the likes of Tina Fey, Billy Murray, Mike Myers, Stephen Colbert and Gilda Radner.

Even with his later prominence, however, Close could look back on the San Francisco scene of the ’60s as providing a perfect storm for generating the off-center comedy The Committee was offering. His colleagues recall how he would sit at a table at Enrico’s and comment on the passing scene. “San Francisco,” he would say, “is the only place in the world where certifiable crazies are performing as functioning members of society.”